For ScotBookFlood publishers reveal what Scottish books they’ll be gifting this Christmas. By choosing one from their own publishing house and one from elsewhere, there’s lots of insight and inspiration here for the book lovers in your life. Join in on social media with our hashtag and tell us what books you plan to gift to family and friends (or maybe as an end-of-year treat to yourself). We’d love to hear from you!

Andrew MacKinnon from Acair is buying…

The first book which I plan on gifting this year will be Sly Cooking – Forradh, by artist Catrìona Black. This is a great wee pocket book featuring little-known Gaelic words, accompanied by fun original linocut illustrations, created by the artist. I plan on giving this book to my mum, who loves learning new Gaelic words that she’s never come across before, even though she has been a fluent speaker all her life!

The second book I plan on gifting this year is Hings by Chris McQueer. This fun, witty new book has been widely praised since its release, and would make a great gift for someone with a sense of humour! My brother is a keen follower of Chris on Twitter, and I know he would love reading more of his quick wit and funny observations.

Jonny Gallant from Alban Books is buying…

My father just moved to Edinburgh, setting up home in a top floor tenement in Bruntsfield with spectacular views. Looking out over the city it’s wonderful to pick out landmarks and piece together a map of the Old Town from the living room. I’ll be giving him a copy of Edinburgh: Mapping the City by Chris Fleet and Daniel MacCannell. Dad (and I) will get great enjoyment learning more about his new city as we gaze over it with mugs of coffee and glasses of wine.

My best friend, Kieran, is a musician and song-writer and I know of no-one else who revels more in the English language. A few years ago, I gave him Ron Ferguson’s excellent biography of George Mackay Brown, but I really should have given him Letters from Hamnavoe. Dipping into this book, just for a couple of minutes, rewards the reader with exquisite turns of phrase, imagery and reflection. It’s a treasure of a book that has stayed with me since I first read it over a decade ago; I think of Mackay Brown and springtime every time my knife goes into butter.

Duncan Jones from ASLS is buying…

A Kist o Skinklan Things, like all the best anthologies, is full of variety – a wonderful gift-box of twentieth-century Scots poems, a mixter-maxter of comedy and tragedy, of love, despair, triumph, rage, beauty, hope, life, and death. Demonstrating the huge poetic range and power of the Scots language, this is an absolute gem of a collection.

James Kelman’s Dirt Road is an extraordinary novel. All Kelman’s novels are extraordinary, of course, but Dirt Road stands out for the virtuoso high-wire act that is Murdo’s stream of consciousness, which we inhabit throughout the book, and for Kelman’s effortless narrative control and deep human sympathy.

Freya Barcroft from Barrington Stoke is buying…

This year I was absolutely blown away by Martin MacInnes’ debut novel Infinite Ground. Though completely lacking in any festive flair, this engrossing journey of a novel is definitely one to be sampled at any time of the year. Pulling on the strings of detective tropes, Martin’s writing goes far beyond the confines of any genre to become a unique and rather unnerving read. It’s definitely one for those ‘I’ve read it all’ readers and I’ll be gifting it to my wonderful mum who’s a more voracious reader than I’ll ever be!

And from our selection of shiny new titles, I’ll be gifting to my little cousin who’s just stepping into the brilliant world of YA, the hilarious and heartbreaking The Last Days of Archie Maxwell by Annabel Pitcher. It’s definitely a book for teen readers searching out more hard-hitting subjects and it is so tightly written and plotted that it’s a wonderfully easy read. Archie’s voice is so real and engaging that I found it impossible not to read in one sitting and I’m sure my cousin will quite happily curl up with his story on a lazy boxing day.

Kirstin Lamb from Barrington Stoke is buying…

It’s an unashamedly biased purchase, but I will be gifting our newly-published I Killed Father Christmas by Anthony McGowan and Chris Riddell. Apart from the obvious festive link, this little book makes a great Christmas gift with a funny, joyful storyline all about the true meaning of Christmas, and with magical illustrations by Chris Riddell – what more could you ask for? I’ll be buying it for my little cousin who has just started to read on his own but will still let me curl up and read with him – the perfect book for sharing with a little one over the holidays!

Elsewhere I’ve already picked up Ian Buxton’s brand new Whiskies Galore: A Tour of Scotland’s Island Distilleries which will be perfect for my dad this Christmas – he’s been a big fan of Ian’s writing since 101 Gins to Try Before You Die and this one will, I suspect, go down even better. (And there’s a small chance he may even discover a distillery he hasn’t yet visited himself!)

Jamie Norman from Canongate Books is buying…

For my father, Alistair Moffat’s The Hidden Ways – an exploration of the history of Scotland’s forgotten roads, it’s a rich and fascinating study of the land, told through the paths Alistair has walked. Something to hopefully rouse dad from the sofa on Christmas day and set him out walking!

For my friend Nicki, I’m paying close attention to the upcoming The Goldblum Variations collection by Helen McClory – as she can quote any of his lines at the drop of a hat, I think this’ll be perfect, plus the concept is hilarious.

Jen Wallace from Canongate Books is buying…

This Christmas, I will be gifting The Hidden Ways by Alistair Moffat to my brother. He loves walking and the outdoors and this book is such a wonderful celebration of Scotland’s natural and social history that I know it will be the perfect gift for him, and hopefully inspire him to do a bit of exploring of his own.

I’ll also be buying a copy of Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman for my mum. I thought it was really heartwarming and made me feel all warm and fuzzy which is the perfect kind of book for snuggling up with over the Christmas holidays.

Anne Glennie from Cranachan Publishing is buying…

This year I’m putting a copy of This Bonny Baby by Kasia Matyjaszek and Michelle Sloan in my nephew Cameron’s stocking. He’s only two, but he loves books and listening to stories. This cute board book will be a winner because it has a mirror inside and gorgeous illustrations of babies making a mess – another one of his favourite past-times!

My cousin Heather has been raving about the recent TV adaptation of Queen Victoria’s life, so I’m hoping she’ll be delighted to receive a signed copy of Punch by Barbara Henderson. Set in Victorian Scotland, runaway Phin finds new friends on the road, including an escaped prisoner and a dancing bear. With a bracing, pacy plot which includes the famous Punch and Judy, Queen Victoria, and even a Victorian Christmas celebration – this is sure to be a festive favourite!

Jayne Baldwin from Curly Tale Books is buying…

How could I not recommend this new title as our children’s publishing company and shop sits right next to Shaun’s extraordinary emporium that has grown over the years into Scotland’s largest second hand bookshop? The Diary of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell is as quixotic and quirky as its author and his business based in Wigtown, Scotland’s National Booktown. The diary format makes it extremely readable and funny combining his jaded views on demanding customers whilst dealing with an eccentric selection of seasonal staff. I’m planning to give copies to several friends and family members so that they hopefully realise that there is more to bookselling than sitting behind a desk drinking coffee and reading! Shaun’s diary reveals the emotional baggage of bookselling including the complications of what may lie in much loved collections left to family to dispose of when the owner dies. And then there’s the day to day difficulty of just trying to make a living out of what many imagine to be their dream job. Surprisingly frank this book has heart in between the hard covers.

Nip Nebs by Susi Briggs, with illustrations by Ruthie Redden, is a beautiful book about winter frost will be hot off the press at the beginning of December. Nip Nebs is the Scots name for Jack Frost and the charming story is suitable for young children but the illustrations by artist Ruthie Redden mean that it has appeal for all ages. The book is in Scots but the language is evocative and lyrical and can be appreciated by non Scots speakers though there is a translation into English as well. I’ll be buying copies for children in the family, but know that their parents and grandparents will love the pictures as Nip Nebs weaves his magic across a winter landscape.

Karyn McMurray from Floris Books is buying…

When Wine Tastes Best is a genius wee book that tells you when wine is at its most delicious. It’s slim, handbag-sized and you can carry it anywhere – perfect for those emergencies when you have to ask yourself, ‘Is this a good day to drink wine?’ I will be gifting this to my best friend this Christmas.

Pretty Monsters is one of my favourite books of all time. This collection of Kelly Link short stories will definitely be going in someone’s stocking: the trouble is deciding which lucky person’s life to make infinitely weirder, funnier and more magical. The only solution is to gift multiple copies…

Eleanor Collins from Floris Books is buying…

I have a lot of 9-12 year olds in my life right now, and that means I’m giving away numerous copies of Lari Don’s wonderful Spellchasers trilogy. It’s gripping, friendly, full of magical adventure and happens to be set on enchanting Speyside. Recommended for Christmas and birthdays.

It wouldn’t be Christmas for my children without the latest Matt Haig Christmas book: Father Christmas and Me, which follows the beguiling A Boy Called Christmas and The Girl Who Saved Christmas. The Chris Mould illustrations are so full of character: stocking-filler gold.

Chani McBain from Floris Books is buying…

I’ll be giving this fun book, Ally Bally Bee illustrated by Kathryn Selbert, to my daughter this Christmas. She’s 2 and loves lifting flaps to discover what’s underneath and the rhyme is a favourite in our house).

A Work of Beauty: Alexander McCall Smith’s Edinburgh will make an ideal present for my mother-in-law who likes nothing better than to lose herself in the history and architecture of a beautiful city.

Leah McDowell from Floris Books is buying…

Full of fun details and bright colours, I know my niece will love The Super Scotland Sticker Book by Susana Gurrea! Especially because it contains lots of places and animals that she sees every day in Scotland.

Surely the festive season is the perfect time to learn the art of over-indulging… As a self-confessed hedonist, I’ll be buying a copy of The Art Of Losing Control: A Philosopher’s Search for Ecstatic Experience by Jules Evans for myself, as well as a few friends and relatives who are also particularly skilled in this area!

Sarah Webster from Floris Books is buying…

Every year at Christmas-time I’m poised and ready to unleash my inner Art Attack (a staple in the TV diet of many 90s kids). A Swedish Christmas: Simple Scandinavian Crafts, Recipes and Decorations by Caroline Wendt allows me to do just that. Packed with creative inspiration from creating your own Christmas crackers and wreaths to recipes for giant gingerbread crowns, this book will fully satisfy my crafting ambitions this festive season.

My sister loves crime thrillers, so I intend to introduce her to some of Scotland’s finest tartan noir with the new Bloody Scotland anthology by various authors. A fantastic taster of so many leading crime writers, it’s exciting and intriguing to find out how they’ve grafted their new crime stories onto some of Scotland’s most fascinating buildings and structures.

CJ Cook from Floris Books is buying…

ALL of my friends will be receiving copies of Chris McQueer’s Hings, from queens of the publishing scene 404 Ink. I don’t think a book has ever made me laugh so much (or made me question my curry choices), and I want to share the joy.

I’ll be sending a copy of Porridge the Tartan Cat and the Unfair Funfair by Alan Dapre to my 9-year-old cat-mad goddaughter. As she’s half-Scottish, I love to remind her of her roots by sharing Scottish books with her. She’s adored the Porridge the Tartan Cat series so far, so I know she’ll be so excited to read his latest cat-lamity!

Shelagh Campbell from Gaelic Books Council is buying…

Le Mùirn/With Affection by Catriona Murray is a very special book which documents the friendship between the renowned ‘Melbost bard’, Murdo MacFarlane and the equally renowned Gaelic singer, Margaret MacLeod of Na h-Òganaich. The book, which is bilingual, includes a number of classic songs which came from this historic collaboration as well as letters, photos, manuscripts and stunning original artworks produced specially for this project. It would make a perfect gift for anyone interested in contemporary Gaelic music.

I’m going to send Mil san Tì? by Seonag Monk by to a friend in Canada who’s learning Gaelic. The story is gripping and often hilarious, the characters are wickedly witty and true to life and I couldn’t put it down. As a Gaelic learner myself, this was one of the first books that I read from page to page without consulting a dictionary!

Laura Waddell from HarperCollins is buying…

This Christmas one of our standout books at Collins is the Explorer’s Atlas, created by Polish illustrators Piotr Wilkowiecki and Michal Gaszynski. It’s an atlas for the incurably curious, for those ready to fall down a rabbithole of the weird and wonderful, as it filled with oddities and tidbits of information. It’s also sumptuously designed, with a palette of forest greens, rich mauves and burgundy against cream and gold. It doesn’t even need to be wrapped with a bow. I guarantee that if you gift this to someone, you will later find them poring over it.

From elsewhere, I can think of many people who should read Rebecca Solnit’s The Mother of All Questions, and the violently chartreuse and navy cover makes it a striking gift, too. I always feel like I can breathe more easily after reading Solnit. I was recently at the Literature Alliance Scotland Literary Cabaret and two speakers quoted her in their review of the past year. The thoughtfulness, clarity and compassion with which she writes on topics of the day feels like a steady, guiding hand through an uncertain world.

James Crawford from Historic Environment Scotland is buying…

Photo by

Paul Reich

Everyone really should know that books are the best presents. It’s what I give – and receive – almost exclusively each year. Every book is your own personal Tardis – little cuboids of paper and words that can contain whole worlds. Whereas socks can only contain your feet…

This year I’ll be giving Bloody Scotland to my father. He’s an avid reader of crime fiction, but primarily concentrates on the big American authors. Which means he needs to be introduced to the incredible crop of current Scottish talent. What better than a book of crime shorts – inspired by Scotland’s iconic buildings – to showcase 12 of the nation’s best crime writers? Featuring the likes of Denise Mina, Val McDermid, Chris Brookmyre, Doug Johnstone and Louise Welsh, this is the ideal primer to lead him to a whole raft of new and backlist titles…

For my brother I’m going to get Geoff Dyer’s White Sands: Experiences from the Outside World. I’ve followed Geoff Dyer’s genre-hopping writing for years now, and find him one of the most interesting and unusual essayists out there. All the same, he is an acquired taste and one I’ve been reluctant to share as a result. So my brother will be a test case! The essays in White Sands offer the perfect encapsulation of Dyer’s amused misanthropy, and his meandering and languorous attempts to explore the most fundamental questions about our existence. To paraphrase the title of one of his previous books, this is existentialism for those who can’t be bothered to do it

Christine Wilson from Historic Environment Scotland is buying…

I will definitely be giving Who Built Scotland: A History of the Nation in Twenty-Five Buildings by Kathleen Jamie, Alexander McCall Smith, Alistair Moffat, James Robertson and James Crawford to my dad this year (although I’m sure my mum will borrow it pretty quickly). He is a real history enthusiast, and I know he has read books by some of the authors before, like Alexander McCall Smith and Kathleen Jamie. My parents live in Glasgow, so I think they will especially enjoy the chapters on Glasgow School of Art and Glasgow Cathedral.

I recently finished re-reading Under the Skin by Michel Faber, which is just amazing. I’ll be giving a copy to my sister this Christmas – she has seen the film, but not read the book. Canongate reissued it as part of the Canons series earlier this year with a beautiful new cover, so it has to be that edition! I might even throw in a copy of The Book of Strange New Things as a bonus gift.

Healey Blair from Muddy Pearl is buying…

Most of us will know someone who loves Christmas – not just loves, but LOVES it. That person for me is my friend Nicola, who loves Christmas so much that one year she nearly ended up in A&E after she got so excited she began to hyperventilate. In order to keep her calm this year, I’ll be gifting her a thoughtful little book that she can read the whole way through the Advent period. Adventure by Mark Greene is a beautiful book of poems and reflections on the wonder and mystery of the Christmas story, perfectly capturing the magic that can be found in the story of Jesus.

My sister is an art student with a brilliant imagination, who loves to invent worlds not unlike our own where blobs of paint and pencil marks are life forms with unique thoughts and personalities. Even after reading just the first few pages of The Humans from Matt Haig, I knew this story of a man replaced by an alien who struggles to understand the human world would be exactly the kind of book a woman who loves to create fantastical realities would enjoy. This insightful and hilarious look at the beauty to be found in messy humanity will be a great read for my sister over the Christmas holidays (and a very welcome break from university reading!)

Taran Baker from Sandstone Press is buying…

Skye the Puffling by Lynne Rickards is going to be one of my Christmas gifts for my adorable 1 year old niece Millie Skye, who shares a name with the wonderful ball of feathers that is Skye the Puffling. She is already obsessed with books, opening and closing them is her favourite part but were now getting to a point where she listening to someone read to her and what could be better than one of Lynne Rickard’s masterpieces.

I’m planning to get my dad the whole William Wisting Series because he loves Scandi Crime, and Jorn Lier Horst’s police procedurals will be just the thing to keep him distracted this Christmas (so Mum and I can watch Strictly in peace). Of course there’s lots in the series to choose from but I’ve gone with When It Grows Dark as it’s the prequel to the first book Dregs and will get him started.

Kay Farrell from Sandstone Press is buying…

My Dad is a big reader of non-fiction, particularly history with a Scottish connection. He especially loves to have new anecdotes to wheel out at social events around Christmas. The Great Horizon by Jo Woolf is perfect for him: it combines stories of some of the world’s most famous adventurers with stories of lesser-known explorers and scientists, mostly Scottish. While there’s a real mix of inspiring stories – my favourite is the indomitable Freya Stark – I think Dad will like the crusty Speirs-Bruce best. He can identify with a man who thought there was no good reason Scotland shouldn’t launch its own Antarctic expedition!

In I Killed Father Christmas! by Anthony McGowan, a boy kills Father Christmas by asking for too many gifts, then proceeds to make amends by putting on his mum’s old red coat and playing Santa himself. I’ve got several children-of-friends to buy for and I can foresee more than one getting this book, especially since Barrington Stoke’s books are dyslexia-friendly. Great story with themes around the consequences of selfishness and taking responsibility, and the illustrations are adorable. I love the robot!

Sue Foot from Sandstone Press is buying…

I’m going to give a friend The Whisky Dictionary by Iain Hector Ross for Christmas. It’s a lovely little book full of whisky terminology and quirky drawings. Just the thing for my friend to cosy up with by the fire and enjoy a glass of whisky.

My second book is How To Stop Time by Matt Haig for my daughter’s birthday. She’s studying abroad and had to leave most of her books at home. With exams looming I think she would definitely like to stop time!

Robbie Guillory from Saraband Books is buying…

Plump stockings rule above all other Christmas traditions in my family, so foraging for the perfect fillers to squeeze in besides the chocolate coins and obligatory potato can take all year. My partner’s stocking is going to have a few hard corners in it, because I’m slipping in the first of Contraband’s Pocket Crime collection, The Paper Cell, a gripping literary thriller by Louise Hutcheson that will be perfect for curling up with beside the fire.

My oldest and best friend lives at the other end of the country, so when we do meet it generally requires feasting. To that end, I’m getting him the beautiful Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat by Samin Nosrat this Christmas, and look forward to the culinary delights to be had in the new year.

Sara Hunt from Saraband Books is buying…

My cousin will be unwrapping a copy of The Accident on the A35 by Graeme Macrae Burnet this Christmas (many of my family and friends are already reading it!) The sheer pleasure of reading Graeme’s novels is due in large part to his outstanding ability to create characters so real, so alive, that you fear, hope, seethe, cringe, lust, laugh and loathe alongside them. Add to that his mischievous wit, understated style, evocative atmosphere, some clever literary flourishes and a detective story. Brilliant!

For another family member who’s currently living abroad, I’ll be sending new illustrated title Who Built Scotland, in which a variety of contributors describe aspects of Scotland’s built (and sometimes natural) landscape. It’s a book for browsers, who will doubtless begin with their own favourite place or author and go on to discover new ones. Apart from my relative’s professional and personal interest in the subject, it’s an effective way of reminding her, ‘Haste ye back.’

Jean Findlay from Scotland Street Press is buying…

I love the word Jolabokaflod – onomatopoeic, it brings to mind a jolly flood of books. For this Christmas book flood, I would give Errant Blood by CF Peterson to my husband because it is a thrilling page-turner set in a Highland winter where the landscape and the weather are almost another character in themselves.

To my father, Peter Findlay, sadly no longer with us, though he is in spirit, I would give Alan Cameron’s Cinico – because it gives the outsider’s view of the Scottish Referendum campaign from a seasoned European. Born a francophone, my father was a witty cynic himself, but this sat with a passionate and uncynical belief in an independent future.

Maria Carter from Swan and Horn is buying…

My elder daughter and her husband are trying for a baby in the New Year. Competent people though they are, they lead incredibly busy lives, so I will be gifting them some treasure in the form of Small Steps to Great Parenting: For Busy Families, by Kalanit Ben-Ari, which packs a lot of punch into a small volume, bursting with realistic, relevant and practical tips based on the best child-development research but without reams of hyperbole!

For my younger daughter, it will be Luke William’s Echo Chamber – she loved the magic realism of Salman Rushdie and Günter Grass, so will thoroughly enjoy the unique literary style of this author and his unique story spanning Nigeria and Scotland, two very significant countries in her own family history.

Sue Steven from Whittles Publishing is buying…

Running South America, with my Husband and other animals by Katharine Lowrie will be perfect for one of my daughters who is a keen runner and has a lot of friends who go running regularly, doing 5Ks and 10Ks. Even in the dark evenings they still go running in the woods but with headtorches on! I know she’ll enjoy Katharine’s amazing story plus reading about all the huge variety of wildlife will make it a book to remember, I’m sure.

Tiddler Sticker Activity Book by Julia Donaldson will be ideal for my two grandsons, aged 2.5 and 5, who absolutely love stickers and I hope they’ll be able to share the book as one will be able to do the the games and puzzles with a little help and of course the stickers will be great for them both. Who knows where the stickers will appear, apart from in the book?!

Eloise Hendy from Vagabond Voices is buying…

There seems to be a slightly unfortunate tradition in my family of giving my mum quite emotionally heavy books for Christmas… Last year my dad outdid himself and gave her Grief Is A Thing With Feathers by Max Porter, leading to tears before turkey. The Outrun by Amy Liptrot may at points appear to continue in this tradition – it concerns alcoholism and isolation in pretty hefty doses – but I found the process of reading it utterly joyous. Liptrot’s book is stuffed full with curiosity, and it’s examination of Orkney’s wild environment is breathtaking. As an aspirational wild swimmer herself, who has recently moved across the country to a new, more rural environment, I know my mum would relish diving into this book. It may sting at first, but you emerge refreshed.

The last book I remember my dad really urging me to read was His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet. He still has it on his bedside table almost two years after finishing it. So what could be better for a fan of history, mystery and the hint of true crime than another story set in Scotland’s murky past? While His Bloody Project conjures a convincing history of a young murderer, Doubting Thomas, by Heather Richardson, follows a genuine criminal – or is he the victim? Focusing on Thomas Aikenhead, the last person to be executed in Britain for blasphemy, this novel is a gripping examination of ethics, medicine and religion in 17th Century Edinburgh. I think it will easily grab my dad from the opening scene’s grisly autopsy onwards.

Check out our Pinterest board for a visual snapshot of all the books chosen here.

Join in on social media with our #ScotBookFlood hashtag and @scottishbooks and tell us what books you plan to gift to family and friends (or maybe as an end-of-year treat to yourself). We’d love to hear from you!

If you enjoyed this then you might like this article of Scottish publisher’s summer reading recommendations.

In the wake of publication of gripping debut novel Doubting Thomas, Vagabond Voices’ immersive digital project, In The Freethinker’s Footsteps, enables readers to experience a taste of Edinburgh’s murky past. In this article the publishers take us behind-the-scenes of this innovative project.

Walking around Edinburgh’s Old Town, it is sometimes easy to feel as if you’ve stepped back in time. The closes and wynds snaking off the Royal Mile can seem like portals; their dark passageways and evocative names pulling you into a gothic past (Fleshmarket Close is a personal favourite). But what would it have really been like to stroll the streets in the 17th Century, when religious doubt could get you locked in the Old Tolbooth?

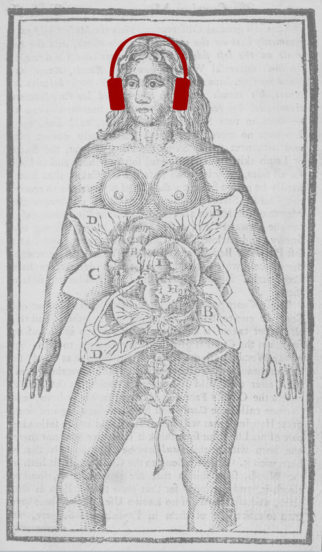

‘The figure explained: being a dissection of the womb…’. Wood engraving showing woman dissected to expose child in womb.

From The Compleat Midwife’s Companion: Or the Art of Midwifery Improv’d, by Jane Sharp (1724).

With Vagabond Voices’ immersive digital project, In The Freethinker’s Footsteps, you can experience a taste of Edinburgh’s murky past. Using an interactive map of the city, you can uncover soundbites, historical trivia, and stories of sex, drugs and religious outrage at every turn. The project has grown out of Heather Richardson’s novel, Doubting Thomas, which inspired by the fascinating true story of Thomas Aikenhead, the last person to be executed in Britain for blasphemy. Told through four different viewpoints, over a span of fifteen years, the book is intimate but wide-ranging; it not only probes into religious conflict, but also offers insight into 17th Century medicine, law and sexuality. Opening with a grisly autopsy of a pregnant prisoner, the novel is saturated with suspicions of the body and its desires, as well as affairs of the soul.

Vagabond Voices’ digital project stretches the story beyond the bounds of the printed book, to explore the notable people, places and items found in Heather Richardson’s well-researched novel. The interactive map of Thomas’s Edinburgh is not only accompanied by audio clips and quotes, but by a five-episode podcast series exploring different elements of the book. In the first episode – available now online – Stewart Ennis reads Thomas Aikenhead’s final words, written shortly before his execution in 1697. Upcoming episodes will feature discussions with Heather Richardson, Dr Michael Graham (The Blasphemies of Thomas Aikenhead), and Dr Catriona MacLeod, an expert on women in 17th Century Scotland. If it was no longer common to execute people for blasphemy in the late 1600s, what doomed Thomas to such a harsh punishment? What would a woman’s experience have been like at this time?

Author of Doubting Thomas, Heather Richardson.

The 17th Century in Scotland throws up a host of questions, riven as it was by religious and political discord. Censorship was rife, with many books branded dangerous for public consumption. Doubting Thomas references many banned texts – the ones that led to Thomas’s arrests for “freethinking”. These are also available as part of In the Freethinker’s Footsteps, under the guise of the Freethinkers’ Library. If you wonder which ideas would have thrown you in jail next to Thomas, you can poke your nose into a clutch of licentious and strange texts, from Christianity Not Mysterious, to the very pamphlet that may have sent Thomas to his death: his classmate Mungo Craig’s A Satyr Against Atheistical Deism: An Account of Mr. Aikenhead.

It might not be possible to walk down a wynd and emerge blinking in 17th Century sunlight, but with In the Freethinker’s Footsteps you can get a couple of steps closer.

You can find In the Freethinker’s Footsteps here. Doubting Thomas by Heather Richardson was published by Vagabond Voices on 26th October 2017 priced £11.95. You can read an exclusive article from Heather, ‘Politics, Potions and Pamphlets in 17th Century Edinburgh’, here on Books from Scotland.

You can find In the Freethinker’s Footsteps here. Doubting Thomas by Heather Richardson was published by Vagabond Voices on 26th October 2017 priced £11.95. You can read an exclusive article from Heather, ‘Politics, Potions and Pamphlets in 17th Century Edinburgh’, here on Books from Scotland.

In the Freethinker’s Footsteps was made possible thanks to Publishing Scotland’s Go-Digital Fund.

James Hogg, also known as The Ettrick Shepherd, is remembered today as the author of the unsettling novel The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner. To his contemporaries, though, he was better known for his poems and for his stories – especially his supernatural tales – which often drew upon Scottish folk beliefs. David Robb introduces Hogg and his work here, and you can also read an extract from Hogg’s dark doppelganger tale Strange Letter of a Lunatic.

Extracts from The Devil I Am Sure: Three Stories by James Hogg

By James Hogg

Published by ASLS

Introduction

By David Robb

James Hogg, “The Ettrick Shepherd” (1770–1835), was a prominent member of the literary world of Walter Scott’s Edinburgh. A shepherd indeed, he was born into a farming family at Ettrick, south-west of Selkirk. His mother, Margaret Laidlaw, a noted tradition-bearer, provided ballad material for Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. Hogg himself was drawn to literature while still a teenager and wrote poems and plays for local entertainment. He began, however, to have poems printed in periodicals and in 1801 he published his first collection, Scottish Pastorals.

At first, his reputation was as a poet, although he also published on sheep-farming. In 1810 he moved to Edinburgh with a view to making a literary career and started his own weekly periodical, The Spy, which ran for a year. It was his long poem The Queen’s Wake which, in 1813, cemented his reputation. However, it was his involvement in the newly launched Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in 1817 which turned him into a star: he was at the heart of its boldly scurrilous and innovative journalism and became the principal attraction (as a fictionalised character) of its long-running series of the Blackwood’s group’s supposed table-talk, the Noctes Ambrosianae.

He continued to write poems and songs, and tales which drew on the history, legends and fairy beliefs of the Scottish Borders. In 1818 he published a full-length novel, The Brownie of Bodsbeck, encouraged (as were others) by the fashionable enthusiasm for Scottish fiction sparked by Walter Scott’s Waverley Novels. In 1822 he published an even more innovative work, steeped in his Romantic vision of Border history and legends, The Three Perils of Man, which was followed a year later by The Three Perils of Women. In 1824 there appeared an equally ingenious and original novel, The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner. This is now regarded as his masterpiece. Always a kenspeckle personality in the circles around Scott and Blackwood’s, he created one of the most distinctive bodies of work, in poetry and prose, of the Scottish nineteenth century.

And in the nineteenth century, it was probably for his tales and poems, rather than his novels, that he was remembered best. In the wake of the modern enthusiasm for The Justified Sinner, however, his stories, with the rest of his substantial output, have had to be rediscovered and reclaimed as achievements in their own right. As regards the three reprinted here, “The Brownie of the Black Haggs” and “Mary Burnet” appeared in Blackwood’s in 1828, and “Strange Letter of a Lunatic” was published in Fraser’s Magazine in 1830.

His most characteristic fictions, which certainly include these three tales as well as the novels mentioned above, are usually compounded of several types of source material and narrative interest. In other words, they combine, in varying degrees, stories of the supernatural, stories which draw particularly on the folk beliefs of the Scottish countryside (familiar to Hogg, surely, from his mother’s tales in particular) and stories which reflect a prominent awareness on Hogg’s part of the quirks and possibilities of human psychology. Sometimes, too, they seem to foreshadow the murder mysteries which have become such standard popular reading for more recent generations. The “mix” of these elements inevitably varies from story to story, and this is what makes each of his tales, at their best, stand apart: the reader notes the features which are constantly present in his writing, but finds that Hogg is by no means a formulaic writer and that each of his best tales feels like a fresh inspiration, while being clearly his and no one else’s.

The pleasure for the reader, then, is double and, in a way, contradictory (things being “double” are entirely characteristic of Hogg, in all sorts of ways, as anyone who reads a number of his works can easily ascertain). Thus, the reader experiences, at one and the same time, the escapist pleasure of reading a tale of wonder (a supernatural tale, or a modernised folktale of the fairy people and their doings) and also the pleasing challenge of what we might call a tale-to-be-made-sense-of – in other words, a tale in which we feel challenged to work out what “really” happened. Hogg makes sure that we never succeed. To this end, he is a master of narrative framing: his tales usually rely on the creation of doubt as to what even the narrator can “know” and reliably tell us, either because the narrator is recounting material from a distant past derived from the oral tradition (that great domain of fascinating but unreliable stories), or because the narrator is inherently untrustworthy.

“The Brownie of the Black Haggs” features, obviously, that folk-tale supernatural creature, the household “brownie”, though there is surely room for doubt (again, a constant device of Hogg’s) as to whether Merodach – despite his weird name – is anything other than a very peculiar-looking mortal. As we get into the tale, however, the interest shifts from Merodach to the psychology of the always out-of-control Lady Wheelhope, and the tale is shaped by the destructive spiral of the relationship between the two.

The shape of “Mary Burnet”, on the other hand, is episodic and chainlike: it gives us a sequence of three mysteries, and while we can begin to make sense of it in terms of the possible experiences of real people (at one level, it is a tale of attempted seduction, of disastrous sexual obsession and of a child lost through marriage into a higher social sphere), its principle appeal derives from the fairy-tale quality which pervades it.

As for “Strange Letter of a Lunatic”, the supernatural hints of the opening pages take second place to the psychological puzzle which emerges. In it, Hogg draws less upon the folk heritage of his Scottish background than he does upon the Romantic motif of the doppelgänger. At which point, all readers of The Justified Sinner feel on familiar ground.

Extract from Strange Letter of a Lunatic

By James Hogg

Strange Letter of a Lunatic by James Hogg – has only been published twice before: once in Fraser’s Magazine in 1830; and once by ASLS, in James Hogg: Selected Stories and Sketches, edited by Douglas S. Mack, in 1982.

to mr james hogg, of mount benger

Sir;—As you seem to have been born for the purpose of collecting all the whimsical and romantic stories of this country, I have taken the fancy of sending you an account of a most painful and unaccountable one that happened to myself, and at the same time leave you at liberty to make what use of it you please. An explanation of the circumstances from you would give me great satisfaction.

Last summer in June, I happened to be in Edinburgh, and walking very early on the Castle Hill one morning, I perceived a strange looking figure of an old man watching all my motions, as if anxious to introduce himself to me, yet still kept at the same distance. I beckoned him, on which he came waddling briskly up, and taking an elegant gold snuff-box, set with jewels, from his pocket, he offered me a pinch. I accepted of it most readily, and then without speaking a word, he took his box again, thrust it into his pocket, and went away chuckling and laughing in perfect ecstasy. He was even so overjoyed, that, in hobbling down the platform, he would leap from the ground, clap his hands on his loins, and laugh immoderately.

“The devil I am sure is in that body,” said I to myself, “What does he mean? Let me see. I wish I may be well enough! I feel very queer since I took that snuff of his.” I stood there I do not know how long, like one who had been knocked on the head, until I thought I saw the body peering at me from a shady place in the rock. I hasted to him; but on going up, I found myself standing there. Yes, sir, myself. My own likeness in every respect. I was turned to a rigid statue at once, but the unaccountable being went down the hill convulsed with laughter.

I felt very uncomfortable all that day, and at night having adjourned from the theatre with a party to a celebrated tavern well known to you, judge of my astonishment when I saw another me sitting at the other end of the table. I was struck speechless, and began to watch this unaccountable fellow’s motions, and perceived that he was doing the same with regard to me. A gentleman on his left hand, asked his name, that he might drink to their better acquaintance. “Beatman, sir,” said the other: “James Beatman, younger, of Drumloning, at your service; one who will never fail a friend at a cheerful glass.”

“I deny the premises, principle and proposition,” cried I, springing up and smiting the table with my closed hand. “James Beatman, younger, of Drumloning, you cannot be. I am he. I am the right James Beatman, and I appeal to the parish registers, to witnesses innumerable, to———”

“Stop, stop, my dear fellow,” cried he, “this is no place to settle a matter of such moment as that. I suppose all present are quite satisfied with regard to the premises; let us therefore drop the subject, if you please.”

“O yes, yes, drop the dispute!” resounded from every part of the table. No more was said about this strange coincidence; but I remarked, that no one present knew the gentleman, excepting those who took him for me. I heard them addressing him often regarding my family and affairs, and I really thought the fellow answered as sensibly and as much to the point as I could have done for my life, and began seriously to doubt which of us was the right James Beatman.

Strange Letter of a Lunatic by James Hogg – has only been published twice before: once in Fraser’s Magazine in 1830; and once by ASLS, in James Hogg: Selected Stories and Sketches, edited by Douglas S. Mack, in 1982.

Strange Letter of a Lunatic by James Hogg – has only been published twice before: once in Fraser’s Magazine in 1830; and once by ASLS, in James Hogg: Selected Stories and Sketches, edited by Douglas S. Mack, in 1982.

The Devil I Am Sure: Three Short Stories By James Hogg, introduced by David Robb, is out now published by ASLS. You can view, and download, the PDF for free here.

404 Ink’s third book heralds collaboration with rock band Creeper this November, to accompany the Theatre of Fear tour which heads across the UK in December. The Last Days of James Scythe dives headfirst into the band’s music, and an eerie world not wholly our own, by exploring The Stranger, Callous Heart, and more. Books from Scotland spoke to illustrator and designer David Ransom about being part of this ambitious project.

How did working with Creeper come about and what kind of work have you done with them prior to The Last Days of James Scythe?

I’ve known three of the band members Will, Ian and Dan for years now having all come up in the music scene in Southampton so we’ve all played shows and hung out together. Through that we soon discovered we were all equally as nerdy about the same things, so it was really great to start working on projects together with them. The first thing I did for them was design a poster for their Southampton show in March. We did a run of 100 hand-screened prints and auctioned a signed one off for charity, so that was a really cool thing to start with. I then produced the ‘Inside Room 309’ Misery screening at the University here in Southampton which, again, I made some screened posters for and “themed” the event. Will and I spend a lot of time coming up with ideas and projects to work on which is obviously really great as a Graphic Designer, I get to do some really cool things that I wouldn’t normally get to do.

For those unaware, who is James Scythe and why should we be interested in his last days?

James Scythe was an officer for The Ombudsman of the Preternatural, who are a branch of the Government who investigate the weird and wonderful things in the UK. Toward the end of 2015 James was sent to Southampton to investigate a story of a dark apparition that has been sighted many times in the city. Unfortunately, disaster struck during his investigation and his life was changed forever.

What has been your role on the book? What has been your favourite part working on it?

My role in the book has been primarily as a designer. There have been lots of artefacts of James’ life that we’ve needed to create and expand, to make him a real, three dimensional part of the world. But as well as that I worked closely with Ian and Will, as well as 404 Ink, to write and flesh out James’ back story; who he is, where he’s from and what really happened to him.

The Last Days of James Scythe comes out in a month – how do you feel about your first book credit?

Extremely excited! Terrified, but extremely excited. I always want to be busy, so it’s great to have a big project like this to get my teeth into. I can’t express how grateful I am to the guys in Creeper and 404 Ink for letting me work on this. I spent the last 10 years working as a photographer and I’ve only been working as a Graphic Designer for a few years now, so I’m really lucky to be able to do this kind of work so early on.

Any recommended Halloween reads for the road?

What’s great about working as a Designer is I can listen to audiobooks all day! I always have something on my bedside table to physically read, but it also means I can churn through a lot of books during the day. Like most people right now I’ve got Stephen Kings’ IT lined up and ready to go, but Phillip Pullmans’ Book of Dust has just come out so Pennywise will have to wait! In terms of Halloween themes, The Rivers of London books are fantastic, but I’m too much of a wuss to read anything actually scary.

The Last Days of James Scythe: A Report for the Ombudsman of the Preternatural can be preordered for £20. You can catch 404 and Creeper at the Theatre of Fear tour on the following dates:

The Last Days of James Scythe: A Report for the Ombudsman of the Preternatural can be preordered for £20. You can catch 404 and Creeper at the Theatre of Fear tour on the following dates:

Dec 3: Glasgow

Dec 4: Birmingham

Dec 5: Bristol

Dec 7: London

Dec 9: Manchester

Dec 10: Southampton

If you relished reading about Mildred Hubble’s magical moments in The Worst Witch, then you’ll love meeting Ruby McCracken in this fun brand new book. Pre-teen witch Ruby is forced to move to the ordinary world and give up spells, Hex factor and her broomstick. Tragic! Here we introduce Ruby via her Guide to the Ordinary – or ‘Ord’ – world, where many of our everyday customs are absolutely baffling to Hexadonians like Ruby.

Extract from Ruby McCracken: Tragic Without Magic

By Elizabeth Ezra

Published by Floris Books

Ruby McCracken: Tragic Without Magic by Elizabeth Ezra is out now published by Floris Books priced £6.99. Find out more about how the book’s fantastic cover design came about through the Kelpies Design and Illustration Prize in this article also on Books from Scotland.

Elizabeth Ezra was born in California, has lived in New York and Paris, and now lives with her family in Edinburgh. She teaches at the University of Stirling and writes children’s books in her spare time. In 2016 she won the Kelpies Prize for new Scottish writing for children.

In Supernatural Scotland children can discover many weird and wonderful stories, from beasts and brownies, to selkies and storm witches. This extract on ghosts and graveyards introduces supernatural spirits including an undead sailor in Sutherland and the Ghost of Culloden moor.

Extract from Supernatural Scotland

Part of the Scotties series for children

By Eileen Dunlop

Published by NMS Publishing

Ghosts and Graveyards

Since the beginning of time, people have believed that the spirits of the dead haunt places where they lived. Every country in the world has its own ghost stories.

In Scotland, the belief flourished in the ill-lit streets of the towns and cities, and the lonely glens and hills, where it was easy to imagine on a dark winter night that a ghost might be flitting behind you. Ghosts did not appear simply to frighten people – sometimes they came to right a wrong done in life, like stealing money or cheating a relative out of a title or property. Sometimes they were murderers who had been denied Christian burial and could not rest in their lonely graves.

Naturally ghosts were associated with graveyards, and memorial stones were carved with skulls and other symbols of death. It was believed that although spirits were allowed to haunt by night, they must return to their coffins when the cock crowed at dawn.

The weeping tombstone. In the churchyard of Inchnadamph in Sutherland is a vault, unused since the early 20th century, which holds the bodies of the MacLeod chiefs of Assynt. On one of the flat tombstones there is a spot of damp about ten centimetres across, which never dries out – even in spells of hot weather. The roof is in good repair, the ground is not waterlogged, and no other stone shows any sign of damp. Local tradition claims that before a major catastrophe, such as a war, the moisture turns to blood.

Ghost of Culloden. Culloden Moor, Scotland’s saddest battlefield, is haunted by a tall Highlander with a pale, tired face. He whispers ‘defeated’ to all those he meets.

The undead sailor. Three hundred years ago, a Polish ship was wrecked at Sandwood Bay in Sutherland. Many sailors drowned. It is said that the ghost of one of them often knocks at the door of a certain cottage. Anyone foolish enough to open the door sees a horrifying sight – a headless man outlined against the grey, stormy sea.

Eileen Dunlop has written over 20 novels and works of non-fiction for children, including Saints of Scotland in the Scotties series. Scotties are exciting, full-colour, Scottish information books for young readers, for children living in Scotland or for visitors. Each title has 40 full-colour pages plus an eight-page black/white facts and puzzle section (photocopiable for classroom use), and contains a wealth of interesting facts, stimulating activities, websites, and suggestions for places to visit.

Eileen Dunlop has written over 20 novels and works of non-fiction for children, including Saints of Scotland in the Scotties series. Scotties are exciting, full-colour, Scottish information books for young readers, for children living in Scotland or for visitors. Each title has 40 full-colour pages plus an eight-page black/white facts and puzzle section (photocopiable for classroom use), and contains a wealth of interesting facts, stimulating activities, websites, and suggestions for places to visit.

Supernatural Scotland by Eileen Dunlop is out now published by NMS Publishing. In it you can find out about:

- Ghosts and Graveyards – including the Undead Sailor, and the Weeping Tombstone

- Haunted Houses – such as Haddington House with its ghostly horse

- Witches – for example, Morag the Storm Witch who sold good winds to sailors for sixpence

- Halloween – guising, and Mischief Night (as Halloween was called in the Hebrides)

- Fairies – fallen angels, household helpers, changelings, and more

- Glaistigs and Brownies – a glaistig is a thin woman with a face like ‘a grey stone overgrown with lichen’

- Merfolk – from golden-haired mermaids to the Blue Men of the Minch

- Beasts Great and Small – like The Fairy Dog. The fairy dog (Gaelic: Cù Sith) had a dark green coat. He was kept as a watchdog in the fairy hills and feared by all humans…

Queen of Teen, Juno Dawson, and prize-winning illustrator, Alex T Smith collaborate in this chilling tale of love, death, black magic and what follows when they all come together. A contemporary take on the Gothic genre, Grave Matter’s stylistic tone, in both prose and illustration, provides a perfect primer for Halloween’s ghostly goings-on, as this chilling opening demonstrates.

Extract from Grave Matter

By Juno Dawson

Published by Barrington Stoke

Chapter One

There is still snow on the ground when they lower her into it. The same snow, I suppose, as the night she died.

I’m drunk. Everything is fuzzy at the edges. My eyelids are sore and swollen, my blinking sluggish. A vodka filter. The snowy graveyard swims in and out of focus. If I squint, grey stick-men cluster around her grave.

All is black and white, with only the lilacs atop her coffin for colour. They were her favourite.

*

Don’t let me go.

I won’t.

She gripped my hand. Pale fingers, ebony nails.

Please, Samuel…

I promise I won’t. I won’t let you go.

Her grip went slack.

*

My father is sombre, professional, as stiff as his vicar’s collar. It is his job to be solemn, but I wonder if today he means it. I think he must – everyone who met Eliza loved her.

“In the Name of God,” my father begins, “the merciful Father, we commit the body of our daughter and friend Eliza Grey to the peace of the grave.”

Mrs Grey is wailing, burying her face into the lapel of Mr Grey’s coat. Her pained cries – animal somehow – soar and swoop through the naked winter trees, shaking crows from the branches. Tears stream down her chin. No one knows what to do to comfort her. Other mourners politely pretend her grief isn’t happening, they shift from foot to foot, unsure of what to do with their hands.

My limbs feel too long and limp, like over-done spaghetti.

The coffin is lowered into the earth. At the flick of a switch, the device cranks and wheezes to life and the coffin descends. It seems too small by far to contain Eliza. It’s all wrong. To box her is grotesque, like caging a hummingbird.

*

Are you OK to drive in this weather?

Of course, it’s not that bad.

I don’t know, Sam, that snow is pretty seriously snowy.

It’ll be fine, it’s not even settling. Promise. We’ll be home in ten.

*

Every time I close my eyes I see that moment play on a loop. Eliza looked out of the bay window at Fish’s house, watching feathery flakes swirl under the street lights. That was the fork in the road. We could have spent the night at Fish’s.

But we didn’t. We took the other prong. I made her.

Father stands where the headstone will be. He goes on and on.

“Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust. May the Lord bless her and keep her, the Lord make his face to shine upon her and be gracious unto her, the Lord lift up his face upon her and give her everlasting peace. Amen.”

Amen.

My father throws the first dirt on top of Eliza’s coffin. We must all play our part in burying her. The mud rains down on the lilacs, spoiling them. Next, Mr Grey steps forward, Mrs Grey still under his arm. He too throws dirt over his daughter.

It’s all too much. We can’t … we can’t smother Eliza like this. How … how will she breathe down there? She doesn’t belong in the dark and cold. She was scared of the dark.

I fall to my knees. I feel icy slush seep into my trousers. “No!” I cry, and I reach for Eliza’s coffin far below. I scramble to the edge of the grave. “No, you can’t! Eliza!”

Burly hands grab my arms and drag me away. I kick and struggle but strangers hold me back. Mrs Grey wails anew. Father looks so disappointed.

***

Mother’s hand unfurls and I see that a tiny, pale blue pill rests in her palm. “Here,” she says. “Take this. You’ll feel better.”

Her lips are taut, her eyes stern. She – Dr Beauvoir – knows best.

“What is it?” I ask.

“Just take it, Samuel. You need to rest. You haven’t slept since the crash. I hear you pacing around.”

“I don’t want it.”

“Just. Take. It.”

Reluctant – because I worry I’ll be stuck in the nightmare – I swallow the pill. Mother grips my face to check under my tongue. “Good boy. Now, I’d better get over to the Wake.”

“I should be there.”

“After your performance at the graveyard? I don’t think so. Sleep. We’ll be back to check on you in a few hours, but your father needs to be there.”

She helps me out of my black blazer and I pull off my tie. My curtains – thick crimson velvet like all the others in our house, the rectory – are shut. They block out every drop of crisp winter light. “Now, lie down.”

I do as I’m told and she pulls the patchwork quilt up over me. “Mum…”

“Yes?”

“I don’t … I don’t know what to do without her … I can’t live without –”

“Samuel, don’t even say it.” Mum perches on the edge of my bed and her pine green eyes soften. The same eyes as mine. Eliza told me she loved my weird eyes. “I’ve seen this a million times,” Mum goes on. “Don’t tell your dad I took His name in vain, but oh God, the grief will hurt like hell but it won’t last for long. I promise. Every day it’ll get better as you forget –”

“I don’t want to forget her!”

She strokes my hair. It’s short, a number-two shave all over, and her touch comforts me. It somehow reminds me of being a child. “That’s not what I meant,” Mother says. “You won’t forget Eliza, you’ll forget the pain. Eliza wouldn’t want to see you like this and you know it.”

I feel the sleeping pill start to take effect. My head feel like it’s full of black water that’s sloshing around my skull. I say nothing.

“Now sleep.” Mother leans in and kisses my forehead. “Sweet dreams.” She switches off the lamp and I don’t even notice the darkness any more.

Grave Matter by Juno Dawson, with illustrations by Alex T Smith, is out now published by Barrington Stoke priced £7.99.

Grave Matter by Juno Dawson, with illustrations by Alex T Smith, is out now published by Barrington Stoke priced £7.99.

Vampire horror and a serial killer’s story fuse with police procedural in this arresting new debut novel by Andy Davidson. Deep in the sun-baked Texas desert a man becomes a monster – a vampire, by any other name. This tale of Travis Stillwell and his violent transformation will chill you to the core…

Extract from In the Valley of the Sun

By Andy Davidson

Published by Saraband

Travis watched the sky. The sun was soaking through like blood through a garment and soon it would stain everything. He looked all around, up and down the highway, across the fields of tarbrush and yucca and mesquite. The valley a flat bald between the mountains. Nowhere to go, he thought. He had lain awake all night listening to his insides make sounds like the timbers of a new house shifting. You are not dying, the Rue-thing had whispered, her final words before she faded, before the weight of her against his back had lightened, then vanished. You are already dead.

“Hello,” the woman said from behind him.

She stood several feet away, having come on cat’s feet, dressed in a blue bathrobe and holding an orange mug of coffee. The mug was Fireking, a brand he remembered from when he was a boy.

“Pretty, ain’t it,” the woman said of the sky, which was the color of a ripe smashed plum. “How are you?”

“Better,” he lied.

“You look like a man with leaving on his mind.”

He made no answer.

“Where will you go?”

He looked toward that part of the world still dark. “Reckon I’ll keep west.”

She was silent, as if there were something she wanted to say but didn’t know how. The silence stretched between them, and the wind blew across the plains. They could hear, faintly, the sound of a truck shifting up through its gears far away.

Finally, she came out with, “There’s a lot more to be done around here. Tom couldn’t do much after he got sick.” She paused, searching for more words, but they weren’t there, so she drank a swallow of coffee.

Travis looked at her. The wind blew her robe against the shape of her. She was pretty, he thought, but she was thin. He felt a restlessness in his breast, a feeling for which he had no words, a thing he had not felt for a woman in a very long time. It scared him, so he looked away, back to the dawn.

“What got him?” he asked.

“Cancer.”

Travis nodded.

The woman reached into the pocket of her robe and took out a folded bill and held it out. “It’s not much,” she said, “but it’ll get you a ways.”

He did not take it.

“Please,” she said.

He made no move to take her money. Only kept looking west, toward the night. A few lingering stars.

She held the bill a handful of seconds more, then put it back in her pocket. “I don’t mean to insult you,” she said.

“It’s no insult,” he said.

Another silence, and then she spoke, and the words sounded to Travis like the words of a woman who had seen great hardship. They were measured, slow, and flat. “After I knocked on your door this past Sunday,” the woman said, “I got baptized. They call it asking Jesus into your heart. To me it feels like he just walked in of his own accord.” She drank another swallow of coffee.

Travis thought, strangely, of a man named Carson, a man he had not thought of in years. A man who had set whole jungles to blaze with the torch he had carried on his back. There had not been any good men there, no, not one.

“I was never baptized,” he said. “Maybe now I wish I had been.”

“‘Come to me, ye who are weary and heavy-burdened, and I shall give you hookup,’” the woman said with a smile. “And meals at the cafe,” she added, “some pay every week. If you wanted to stay.”

“Meals,” he said. He hunkered down and picked at the rocks among his boots, sifting through the alkali, cupping the bone-chips of some small animal. After a moment, he stood and tossed them, dusting his hands. A centipede crawled among the stones and disappeared into the scrub-grass. “You don’t know what you’re asking,” he said to her.

“I reckon I do,” she said.

After that, she went on her way and left him alone.

Travis watched, helpless, as the sun welled up out of the east and bathed the plains and arroyos and dry creeks in its terrible light. He saw in that flood of gold his own black fate, and he knew that nothing good or purposeful would ever take root in him again.

In the Valley of the Sun by Andy Davidson is published on October 31 by Saraband priced £8.99.

In the Valley of the Sun by Andy Davidson is published on October 31 by Saraband priced £8.99.

New Edinburgh-based publisher Charco Press specialise in translating South American authors into English. This eerie, meditative novel by Richard Romero, narrated by a shy young boy who seems to be very good at lying about the truth, echoes the tradition of sinister rooms in literature such as Dr Jekyll’s laboratory.

Extract from The President’s Room

By Ricardo Romero

Translated by Charlotte Coombe

Published by Charco Press

The house isn’t big, but it’s not small either compared to the rest of the houses on the block. It has two floors, three if you count the attic, a storage room up on the roof terrace where nobody goes apart from me. The rest of the family call it the loft, but I prefer to call it the attic. I didn’t decide this on a whim. It’s something I’ve thought about a lot, up there in the attic, among the old furniture, the trunks, and always the same warmish air capturing the rays of sun as they filter through the skylight and the frosted glass of the door. Rays of sun, skylight, frosted glass. When I’m there, I’m able to think ‘I’m in the attic’, but I find it impossible to think ‘I’m in the loft’. Not everything can be thought. Why should everything have to be thinkable?

On the first floor of the house are the bedrooms. My parents’ room, my older brother’s room and the one I share with my younger brother. There are two large bathrooms that seem much older than the rest of the house, as if they’ve always been there, floating at the height of the first floor, waiting for my family to come and build the house around them. The bathtubs, the taps and the medicine cabinet are majestic; the porcelain, mirror and brass are yellowing in the corners with stains that aren’t stains, because you can get rid of a stain but you can’t get rid of these. I can’t imagine the tap in our bathroom sink without that pale, discoloured cloud underneath it, or the mirror of the medicine cabinet in my parents’ bathroom without the black spots on the left-hand side. However, what really makes these bathrooms feel old, as if they’re of an earlier time, are the tiles covering the walls right up to the ceiling. What is it that makes those tiles so old? I don’t know. I only know that they’re impossible to count. No, that’s not all I know. I also know that although the bathrooms seem the same, like twins, they’re not.

And then there’s the ground floor, which is the same size as the first but seems bigger. It only seems it, though: I know they’re really the same size. And yet, even though I know this, every now and again I feel the need to compare corners and angles, to see how the walls of one floor and another are the same. Or rather: are aligned. The walls of the ground floor and those of the first floor are aligned. However, the ground floor seems bigger.

On the ground floor are the kitchen, the dining room, the living room and the study my father shares with my older brother. There’s another, smaller bathroom, squeezed in between the kitchen and the staircase. There’s a small cleaning cupboard. There’s an entrance hall leading to the front door.

And of course, at the front of the house on the left, looking out over the garden, is the president’s room.

The President’s Room by Richard Romero, translated by Charlotte Coombe, is out now published by Charco Press priced £8.99.

The President’s Room by Richard Romero, translated by Charlotte Coombe, is out now published by Charco Press priced £8.99.

In The Twa Corbies of Cardross, one of twelve crime stories in new anthology Bloody Scotland, Craig Robertson explores the sinister side of Scotland’s heritage. We visit St Peter’s Seminary, once an impressive example of architectural innovation and now a desolate and crumbling ruin, on a cold November morning when the dead don’t seem far away…

Extract from The Twa Corbies of Cardross

By Craig Robertson

Published by Historic Environment Scotland

St Peter’s Seminary, Cardross

As I was walking all alane,

I heard twa corbies makin a mane;

The tane unto the ither say,

‘Whar sall we gang and dine the-day’

I’m Black, he’s Stout. Simple names for simple lives. We work together, best we can. Two sets of eyes can see opportunities in double quick time, take advantage before some other thief can step in and steal your pitch. If he goes hungry then so do I. We’re a team, Stout and me. A team.

‘Where are we going to eat today, Mr Black?’ he asks me.

‘If you want to fly to one of the cities then how about the Witchery?’ I reply. ‘Or maybe the Rogano? I’ve heard the fish at Ondine is the best there is.’

‘Too rich for my blood,’ Mr Stout says. ‘Far too rich. I’m a country bird at heart, a bird of simple tastes, you know that. Besides, my purse is as empty as my belly. Our pickings will have to come as free as the air. What’s fresh on the wind today, Mr Black?’

Stout knew I was joking. The best tables weren’t for the likes of us. Old Stouty and I aren’t welcome, you see. Our faces don’t fit. Not even close. It’s not just that the people don’t want us. It’s that they barely notice we exist.

They don’t see us as we fade into the grey of the sky and the thick of the clouds. We fly in the shadows and pick at their pockets, trip at their feet. We were here before them and will still be here when they are long gone. We see everything and are seen only by the few. We’re in the woods and the concrete, we’re in the rafters and the gloom, we’re deep in the blood of the place.

The truth is we eat anything, Mr Stout and me. That’s how desperately we live our lives. It might be the spoils of the fields or whatever we can salvage from the leftovers of those better provided for. We’d eat each other if we had to. It’s all fair game when you’re hungry.

You’ve never known real hunger unless your belly has been properly empty. Empty like the wind or a broken promise, empty like a past forgotten or a future that will never be. Proper hunger drives you like the devil.

What was fresh on the wind? Well now, there was a question indeed.

In ahint yon auld fail dyke,

I wot there lies a new slain knight;

And nane do ken that he lies there,

But his hawk, his hound an his lady fair.

His hound is tae the huntin gane,

His hawk tae fetch the wild-fowl hame,

His lady’s tain anither mate,

So we may mak oor dinner swate.

Image © Historic Environment Scotland

The place in the woods near Cardross is riddled with corridors and cells, chapels and concrete arches. It’s a derelict house open to all, weather and visitors alike, a dark maze of ruin and stagnant pools, of secluded and secondary thoughts. The tourists might venture there for a thrill or a dare but rarely after lights out, not after the safe company of others has gone home for the night. Then it becomes home to the likes of us and those who would do us harm. In the deep dark, the place in the woods is for dangerous travellers.

They used to call it St Peter’s. They came here, young men all bright and shiny, seeking to learn how best to serve their shepherd. Priests of the citadel, children of the altar, dressed in black smocks from to neck to toe.

One day, the button bright boys left forever and others arrived. Bags of bones with cheeks of flint, eyes dulled and skin grey, these new recruits were not like those who went before. This army served other gods who treated them badly.

Stout and me, we watched them build it, this concrete palace, and we watched it crumble. Years it took as the wind and the rain ate it, chunk by chunk till the woods and the rhododendron swallowed it up, claiming it for their own. No matter how hard you looked, you couldn’t tell where nature stopped and the building started. It’s like that now, at one with the Kilmahew woods and those of us who live in them.

At the edges, its ownership is blurred but at its centre it remains the sanctuary of the boy priests. This was where they came to pray to their god and, of a night or a winter’s morning, you can hear them still, young voices carrying on the wind.

It’s dark and wet down there, guarded by a smashed granite altar, as blind as those who will not see. The sanctuary is a cold bed on a November morning, bitter in the shadows where the sun can’t touch. No place for a soldier boy far from home. No place for the dead to lie out of sight and mind.

Bloody Scotland by Lin Anderson, Chris Brookmyre, Gordon Brown, Ann Cleeves, Doug Johnstone, Stuart MacBride, Val McDermid, Denise Mina, Craig Robertson, Sara Sheridan, E S Thomson, and Louise Welsh is available now priced £12.99.

Bloody Scotland by Lin Anderson, Chris Brookmyre, Gordon Brown, Ann Cleeves, Doug Johnstone, Stuart MacBride, Val McDermid, Denise Mina, Craig Robertson, Sara Sheridan, E S Thomson, and Louise Welsh is available now priced £12.99.

You can find out more about the birth, death and renewal of St Peter’s Seminary in this article on Books from Scotland.

Simon Ponsonby presents a dynamic and comprehensive study of the work and person of the Holy Spirit in this biblical, theological, practical, historical and also accessible book. He outlines early theology and explains the origins of key words including ghost and spirit.

God Inside Out: An In-depth Study of the Holy Spirit

By Simon Ponsonby

Published by Muddy Pearl

The third person of the Trinity is the third article in the creeds, and sadly often ranked third in theology. Yet, as we shall see, ‘from the stand-point of experience, the Spirit is first’. Indeed, notably in the early Orthodox tradition, late fourth-century prayers like the Trisagion (meaning ‘thrice holy’), which undoubtedly reflect earlier devotions, are unapologetic in praying to, invoking and worshipping the tri-personal God. The Spirit was clearly regarded as central to worship very early on. It was only when the deity of the Spirit and the Son, who were worshipped, was placed under threat by errant theology, that the creeds were formulated to reassert the Church’s belief. The doctrine of the Church did not arise at the councils and with the creeds, but was represented and firmly established by ecumenical councils. Theology articulated spirituality and worship, not vice versa.

Nevertheless, in the fourth century Gregory of Nazianzus called the Spirit Theos Agraptos, the God who nobody writes about. Theologians have described him as ‘the Cinderella of theology’, ‘the orphan doctrine of theology’, the ‘dark side of the moon in Christian theology’, and ‘the stealth weapon of the Church’.

The name ‘Spirit’ is a translation of the Old Testament Hebrew word ruach and the New Testament Greek pneuma. Both terms cover a range of meanings, including wind, breath, air, blowing – all of which find resonances in the biblical text. It was not exclusively used for God, but was a term applied to the individual’s immaterial identity (Psalm 32:2); of a demonic entity (1 Samuel 16:14); of the natural wind (Exodus 14:21); and of the innermost soul of a being (1 Corinthians 2:11). The term ‘Ghost’ (from Old German Geist) found in older translations, is now somewhat misleading due to its change in meaning.

As a divine designate, Spirit conveys the idea of a powerful force which smites Israel’s enemies (Judges 14:19); of the breath from God which sustains life (Job 27:3); and also of the mysterious presence of God ‘who blows where it wills’ (John 3:8), whose origin and destination remain elusive. In John 20:22 Jesus prophetically breathes on the disciples and says: ‘Receive the Holy Spirit’, the unction enables their commission – the ministry of forgiving sins where forgiveness is sought in Christ.

The agony of the cross is also the glory, because through it we are restored to God and may receive the Spirit. As Jesus dies, John writes: paredoken to pneuma, ‘he gave up the Spirit’ (John 19:30), not his spirit. Symbolically John is showing that it is the Holy Spirit, not the personal spirit of Christ, which is being released here. Then, after the resurrection, Jesus meets his disciples, blesses them with peace, and breathes on them, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven’ (John 20:22f). The cross is the fount from where the forgiveness of sins is purchased, and from where the Spirit is poured forth.

Owen suggests that a ‘peculiar work of Spirit’ was resting over the Beloved’s body in the tomb, not allowing it to see decay (Psalm 16:10; Acts 2:31). He says: ‘The pure and holy substance was preserved in its integrity by the power of the Holy Spirit, without any of those accidents of change which attend the dead bodies of others.’17 Whether or not this was so, we know that the power of the Spirit was in the tomb, resurrecting, revivifying, raising Jesus bodily from death to life, from the shadows to light, from the grave to glory.

Speaking of this, the ancient apostolic Creed states that Jesus was ‘vindicated in the Spirit’ (1 Timothy 3:16) – his great power worked in Christ when he raised him from the dead and seated him at his right hand in the heavenly places, far above all rule, authority and every power.

God Inside Out: An In-depth Study of the Holy Spirit by Simon Posonby is out now published by Muddy Pearl priced £12.99.

God Inside Out: An In-depth Study of the Holy Spirit by Simon Posonby is out now published by Muddy Pearl priced £12.99.

In Luminous Dark, Alain Emerson retraces his journey through the stages of grief and shock. Choosing to lean into the pain and to face God with his disappointment in a dark tunnel of despair, Alain ultimately finds his way to the light in this thought-provoking personal exploration.

Extract from Luminous Dark

By Alain Emerson

Published by Muddy Pearl

These days I love running in the dark. On winter nights when the air is cold, I set off for a gentle gallop through the streets of my hometown village. Chasing the long shadows of the street lamps as the fog from my own breath dissolves on my perspiring face, I run over the motorway bridge, stealing away from the noise of the late-night commuting traffic, through the spookily serene railway crossing and eventually into the darkness of the countryside. The only thing lighting my path is the low glow of my phone, helping me navigate ankle-damaging potholes and providing a precautionary warning light for the occasional car venturing down these winding country roads. It is dark and still, dangerous and eerie, yet I am not scared.

I no longer fear the darkness.

Even though the night appears vacant, the darkness is filled with, dare I say it, ‘presence’. This is the place where I do my best thinking these days. The night is flooded with mysterious luminosity. It is here my mind and soul are laid bare, the imposter is exposed and my true self revealed. And I rediscover how deeply known and loved I am.

It hasn’t always been that way though.

Like most people I have lived my life scared of the dark, fear gripping hold of my senses on many occasions. From night-time walks as a child, up the creaking long corridor while the whole house was asleep, to wandering the ghostly back streets of townships in Soweto, searching for runaway street-kids as a gap-year volunteer. Darkness for me has been synonymous with fear, confusion and disorientation. It has both frightened and disconcerted me, sending shivers through my spine and causing my knees to buckle.

Yet something changed when I learned, or rather was forced, to stare darkness in the eye, when I was summoned to front it up square in the face. I discovered something liberating happens when we acknowledge the genuine fear we are experiencing from the darkness that surrounds us and yet refuse to let that fear have the last say. Further, the fear is disarmed when we discover there is a light concealed within that very darkness. When we apprehend a certain quality to darkness which draws us further in, beyond what normal feeling or thoughts can comprehend. This is a discovery that cannot simply be learned in abstraction, only encountered as we choose to enter in.

What do I mean? Let me try to explain.