404 Ink’s Inkling series of pocket non-fiction books cover a range of brilliant subjects with fun and insight. The latest in the series takes a look at how popular culture and the apocalypse intersect.

The End: Surviving the World Through Imagined Disasters

By Katie Goh

Published by 404 Ink

The End explores our obsession with the end of the world in culture. What sparked your own interest in the end of the world, and the apocalypse as a concept?

Since I was a kid, I’ve been obsessed with the apocalypse. I used to have this recurring nightmare as a child where I would step on a crack in the pavement and set off a nuclear explosion, so I’ve always had quite an apocalyptic mindset and been worried about my own complicity with the end of the world. I grew up as a teenager in the 2000s, when the end of the world seemed to be everywhere, from pop culture, to politics, to economics, to technology, to the climate crisis. I think growing up in that specific context has also made apocalyptic doomsaying part of my everyday life and cultural awareness.

What drew you to write about the topic in more depth?

I first wrote about my – and society’s – obsession with the apocalypse for The Skinny magazine in January 2020. Then, a few months later, it felt like the end of the world actually did happen with COVID and lockdown. People were talking about the pandemic like it was a movie, and so many people (myself included) turned to art for answers, like the film Contagion or the book Severance. I thought that was fascinating: why are we turning to fictional disasters at a time of real disaster? Surely we would want more utopian escapism?

When 404 Ink did their callout for the book pitches, I thought the COVID context could be a really fascinating jumping off point to explore the relationship between fictional and real disasters which has existed long before this specific pandemic.

Why do you think we – as individuals, and society – are drawn to the end of the world?

At the most basic level, we’re human. We want to survive, and when the world is looking more and more apocalyptic, I think we want to hypothesize about our species’ survival. The end of the world is always actually about the start of a new world, and every single post-apocalyptic story, from The Bible’s Book of Revelation to Station Eleven, features survivors as their main characters. I think as our world, right now, feels increasingly unbearable, there’s an apocalyptic desire to say ‘game over, let’s start fresh.’

What does that offer viewers and readers?

I think it gives us perspective. The best apocalyptic and disaster stories take what’s happening right now and places it in a new context. For example, Squid Game is about the personal debt crisis in South Korea, as well as capitalism, reality television and individualism, but the TV show distills all these ideas into a dystopian ‘what if’ scenario. Having that distance, we’re able to explore these big political, economical and social ideas through characters, plot and theme, and I think that helps us to think about our own world with more clarity.

What is your favourite kind of fictional disaster and why?

I’m a big fan of the asteroid disaster. I think it’s the cruellest disaster scenario because, unlike other types of disasters, it’s not usually man-made and there’s nothing you can do about it (unless you’re Bruce Willis). I think that nihilistic apocalypse allows storytellers to really get at human nature: what are people really like when they have no plan b? I also think asteroid disasters are incredible metaphors. In the book, I explore Lars von Trier’s film, Melancholia, which is a disaster movie about depression. I don’t think a disaster is ever really just a disaster in art, usually it’s representing something else and I love that von Trier makes the end of the world feel intensely intimate and personal.

How did the topic evolve as the world faced a pandemic?

The idea for The End definitely crystallized with COVID, but I didn’t want to just write a book about COVID that would age badly. Instead the pandemic gives the reader a way in to think about disasters and grounds the book in real life to explore more existential ideas, like why are we so obsessed with imagining the death of humanity? I definitely think COVID has made people think more about social inequalities and injustice as the pandemic exacerbated the huge gap between the rich and the poor across the globe. That’s something I was especially interested in exploring in the book, particularly looking at dystopian fiction that similarly uses a crisis to uncover social inequalities that are so often normalized.

You write in depth about the climate crisis in regards to the end of the world – how do you think culture does in addressing the crisis through an apocalyptic lens?

I think in general culture hasn’t fully reckoned with the climate crisis yet – both in real life as an industry that is contributing to the crisis, and as a means of telling stories. You have big Hollywood movies like San Andreas, Geostorm and superhero movies which use imagery that we’ve come to associate with the climate crisis (earthquakes, ice shelves crashing into the sea, faminine, masses of climate refugees), but that imagery is severed from the reality of the climate crisis. It’s used to invoke the fear and anxiety that’s associated with the crisis, but without the real world consequences. I think it’s unfair to totally put the blame on filmmakers, but I think there needs to be a reckoning with how these blockbuster movies are creating a sense of passivity around disaster through numbing audiences to climate crisis imagery.

However, I think there are increasingly more storytellers who are interested, not in recreating the climate crisis on screen, but in exploring the complicated emotions around the crisis. For example, Annihilation is a film and book very much about climate grief but explored through personal grief and a strange, uncanny landscape.

You note that climate as a disaster is so large that films, for example, often struggle to capture the gravity of it. What would be your top reads and watches that do something interesting in regards to climate?

Annihilation is definitely one. And Jeff VanderMeer’s novels, generally, are incredible post-apocalyptic stories about our relationship to the environment. I think novels are really becoming the realm of nuanced fiction about the climate crisis. I would recommend Lydia Millet’s A Children’s Bible, Jenny Offil’s Weather, Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy and Jessie Greengrass’s The High House. There are hundreds of non-fiction books about the climate crisis, but I think fiction can really explore the emotions of living through this crisis – which can be as powerful as fact.

I’m a bit skeptical of climate crisis documentaries which I think can sometimes do more harm than good at numbing people to the horrors of the crisis, but a recent film I found fascinating was A Living Proof by the Scottish filmmaker Emily Munro. Comprising archive footage, the film looks at Scotland’s relationship to the environment across decades and it really highlights how circular our conversations around the climate crisis have been over time.

What are your top tier apocalyptic recommendations? (Books, films, TV, etc)

I’ll pick a recommendation from the four chapters of The End: for a pandemic disaster, the novel Severance which explores globalisation and capitalism through the zombie apocalypse; for a climate disaster, The Day After Tomorrow because I love that silly movie and I think it really did make people sit up about climate change when it was released; for an extraterrestrial disaster, Arrival (or the short story the movie is based on: Story of Your Life by Ted Chiang), which is about aliens and determinism; and for a social disaster, The Parable of the Sower which is one of the most powerful (and hopeful) dystopian novels I’ve ever read.

The End: Surviving the World Through Imagined Disasters by Katie Goh is published by 404 Ink, priced £7.50

Science fiction novels play with the very many possibilities of how our world – and other worlds – can change. In the futuristic Earth that Jamie Mollart has created in his latest novel, natural resources are dwindling, the waters have risen, and hibernation is deemed a possible solution.

Extract taken from Kings of a Dead World

By Jamie Mollart

Published by Sandstone Press

Nobody talks. They keep their eyes on the ground in front of them. I understand. It’s hard to bring yourself around anyway and after The Sleep you are initially left with a desire to be insular. The limited time people are Awake tends to make people shy away from idle chit-chat to begin with. Too much to do when you first Wake. Not enough time and too much to do.

This is one of the things I miss, sitting around and talking. When I lived in London, in the days before the waters rose when it was still the capital, I used to spend hours strolling along the South Bank; sitting outside Gordon’s wine bar with a bottle of red wine that seemed to go on and on. Gordon’s is gone now. The Houses of Parliament. St Paul’s. Buckingham Palace. All of them swallowed by the murky waters of the Thames as it spread out across the country.

A scream startles me back to the present. A woman hits the pavement in front of me, her head bouncing off the tarmac. A cut opens on her forehead and her blood spreads out across her face, dripping on the pavement where it is soaked up by the dust. She pushes herself up to her knees and shakes her head. Drops of blood to land at my feet and she turns back to the Mart and begins shouting, her words quick, high-pitched, angry, indecipherable.

In her right hand she clutches a plastic bag, swings it around her head and launches it at the window. Powdered milk explodes from within it, showering the queue in white dust. Shock holds people still, then a solitary man shouts at her, telling her to watch it, calling her a bitch. She’s crying now, through her sobs shouting, ‘It’s not enough, it’s not enough, I can’t feed them all, it’s not enough!’ Then she realises what she’s done and falls to her knees to try to scrape the food back into the tatters of the plastic bag.

A young man in the queue realises what is happening and quickly squats down and pockets a carton of food that has escaped from her bag. Instinct makes me want to stop him. The camera on the wall tells me otherwise.

The man in front of me sees him too, though, and confronts him. ‘Oi you little fucker, give it back to her, it’s hard enough without you stealing what she’s got.’

I feel a flash of shame.

The young man sneers at him, scoffs and turns away. The older man taps him on the shoulder, but is ignored, so he punches him in the back of the head. I hear the crack as the young man’s face hits the wall. He drops to the floor.

The camera above my head whirrs, and I look up at it as it focusses on the older man. Immediately I realise my mistake, raise both hands and step away from them. I make sure it’s obvious this is nothing to do with me.

My body tenses. The adrenaline of remembered violence pumps through me. When I was younger, this was how I dealt with things. Memory pulls my fists tight, my shoulders straight, readies my body for impact and retaliation. I feel alive.

I’m awake now. Too awake, I have to suppress it. The camera has to see a tired old man, scared of the violence he sees in front of him, not thrilled by it. I force my shoulders to relax. I lower my head. I stretch my hands out, hold them flat against my legs. I concentrate on slowing my heartbeat down.

The younger man is on his feet now, his face a mess. His eyes are pure anger. He grabs the older man by the throat, and punches him twice in quick succession, once in the stomach, once above his eye. They wheel around holding one another, too close to hit each other, just careening about. The queue moves around them as one, like a flock of birds. Aware of the camera, no-one wants to appear involved, to step in and stop it, so they concentrate instead on keeping out of the fray whilst trying to maintain their position in the queue.

All the time, the woman is on her hands and knees scraping white powder into a tattered plastic bag.

Suddenly the street is full of sirens and blue lights. A Black Maria is beside us. The doors slide open and five Peelers jump out, clad in riot gear. For a second I feel sorry for them having to be called out like this so soon after Waking, but then they are upon the fighting men with sticks and boots and fists and all of my sympathy is gone.

Within seconds it’s over. Both men and the woman are gone. With a purr of electric motor the Black Maria is gone and the only evidence any of this ever happened is the blood in white powder and a smear across the wall where the young man’s face made contact. The queue silently reforms. No-one jostles for position. Where people were lost in their own worlds they now look around, joined in a collective fear.

Slowly the queue inches forward again. I step over the blood on the pavement. My feet leave prints in the powder.

Eventually I am at the door. A bored security guard in a uniform that looks too big for him scans my ID and lets me in.

Inside the Mart, the lights are dimmer. Images of Rip Van are plastered on the walls, cardboard cut outs of him hang down on wire hooks above every aisle. Piped music, calming and nondescript, fills the stale, recycled air.

I check the obligatory Chronos clock that hangs in the centre of the ceiling. I’ve been gone much longer than I would have liked. I can’t imagine that she’s still Asleep. The Tranqs will have left her body by now. Please Chronos, I don’t ask you much, but please keep Rose safe. Please let everything be OK when I return.

Quick, Ben, you need to be quick now. I am practised. Every shopping trip as far back as I can remember has been like this: the frustration of the queue then the rush to get what I need and get back. This I can still do.

I grab only the essentials powdered milk, eggs, vegetable supplements, bottles of water. I am careful, adding up as I go along, but when I get to the checkout I realise I have overspent and have to leave some of the shopping with the cashier. She is even more bored than the security guard.

I would never be able to do what they do. The early Wake Ups and being here to face the scorn of everyone else are not worth the pitiful few extra Creds they get. The cashier doesn’t even look at me as she scans my ID card. I try not to register how few Creds are left on it as they flash up on my display and concentrate instead on packing efficiently so I don’t have too many bags to carry. I fit it all in four. Four bags to last us the month. It will be tight.

Outside, a kid is pouring water over the powder and blood mess and trying to sweep it out into the street, but the water is turning the powder back into milk and the mess is just getting bigger and thicker.

I step over it and hurriedly retrace my steps. While I’ve been at the Mart the sweepers have been and the drifts of rubbish are gone. Lights are on in most of the apartment blocks and someone is playing loud hip-hop music which spills out from an open window and bounces out across the square.

Back in our apartment block I pray as I press the lift button and am both surprised and relieved as the button lights up and I hear the motor whirr. While I wait, I put the bags at my feet and watch as the blood floods back into the creases the handles have made in my skin.

The lift arrives, doors shuddering open. The lights inside flicker on and off, then off again and the interior is black dark. I hesitate, think about the stairs and, pushing my bags with my feet, enter the darkness. The doors shut and I climb. Above the door, crimson numbers mark my ascent. Between floors four and five the lights spark on for a second and I catch a glimpse of my reflection in the mirrored walls. I’m shocked at how thin I look, how old, how tired. A ghost of a man.

I pause at the front door. Rest my forehead against the metal and pray to Chronos everything is OK inside. Hold my breath as I push my ID card into the key slot.

The door clicks open and I work my way inside, pushing it with my toe. I place the bags on the floor and close the door behind me. The hallway is fine, from what I can see of the kitchen that’s fine too. I can hear the TV, volume low. She’s Awake.

It allows me to hope, it gives me something to cling onto. I walk down the corridor and enter the lounge, pasting a smile onto my face.

Kings of a Dead World by Jamie Mollart is published by Sandstone Press, priced £14.99.

Selva Almada’s powerful writing continues her novel Brickmakers, which looks at the troubled, violent lives of those who live and work in dusty, rural Argentina getting closer to ruin.

Extract taken from Brickmakers

By Selva Almada

Published by Charco Press

The Mirandas’ finances weren’t doing so great either. Elvio Miranda was a good brickmaker, maybe the best in town, shored up by his family history in the trade, but he was another man who liked to do things his way and didn’t keep up with the work. He preferred training his racing dogs to shovelling soil all day long and carting it to the pisadero. Every so often he’d hire some young guy to help, but since he didn’t keep up with the wages, either, the helpers all left in the end.

If they had enough to eat, it was only because Estela took charge of the household finances and started doing people’s sewing.

When she was a teenager, Señora Nena, her godmother, sent her to study dressmaking, and though she hadn’t made more than a couple of dresses – there was no need, she worked and her godmother never let her want for anything – she’d gone back to it later, helping with the costumes for the carnival dancers. She’d always been an enterprising woman, and though she let Miranda convince her to quit her job as a secretary when they married, on seeing the way things were going, she sent for the Singer from her unmarried days and put signs up in the local stores offering basic sewing services.

Señora Nena had told her that money worries could spoil even the best of marriages, and Estela, who had married for love and meant it to last, refused to let that happen to them. Elvio Miranda may have been useless, but she adored him, he was the father of her child and the man she hoped to grow old with: if he wasn’t going to earn any money, she’d make sure they had at least enough to get by.

Without Miranda’s addictions, which she indulged as if the man were a child, they’d have been better off: from alterations, hemming and mending, Estela quickly moved on to making clothes, and soon she was sewing her first wedding dress. It wasn’t that Miranda asked her for money or took any from her in secret, but rather she, not wanting her husband to feel like less of a man, always slipped something into his pockets to tide him over.

*

Marciano lifts one arm – the effort is agony – and strokes his father’s cheek, his stubble; he tries to reach his hair, which is longer than before, wavy and brown, but his arm falls back and hits the ground with a thud, like an old lady fainting at a funeral. He looks so young, his father. As if no time had passed.

‘Dad, remember when we went hunting in Entre Ríos?’

Miranda laughs.

‘’Course. In Antonio’s pickup.’

Marciano had loved it, it was like The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, the thick vegetation on either side of the river, the muggy heat, the insects. They’d taken a little motorboat and followed the water as it wound its way between the small islands.

He was eleven. The following year, in just a few months, in fact, his father would die. But at the time, his dad was full of life. Miranda had longer hair then and a longer beard, too, and the steam that came from the banks, or from the river itself, from the sun that beat down on the riverbed and warmed up the silt, the steam in the atmosphere, dampened his hair, stuck it to his head and face. He smiled and gazed into the distance. Antonio did, too. The older men didn’t speak and neither did Marciano. As if the landscape had left them breathless. All you could hear was the noise of the engine and the water the boat was slicing through.

Eventually they stopped and got out, wading through the water, then Antonio and his father pulled the boat up the little sandy beach and they made a fire. Night was beginning to fall, but where they were, with so many trees, it was already dark.

That evening they ate a rice stew. The men stayed up chatting till late, swapping stories from hunts gone by, their own and other people’s, comparing notes on how to catch a capybara.

Marciano lay on a mat and listened for a while, wanting to learn, to memorize all the stories so he could boast to his friends, until the men’s voices began to fade, merging with the rustling plants and the water, the squawks of nocturnal birds, the sound of a snapped twig now and then under an animal’s feet.

‘Remember when I said I wanted to go and live there?’

Miranda says nothing. He’s gazing into the distance, like that time on the boat, but he doesn’t smile.

‘Remember, Dad?’

‘Hmm?’

‘Me wanting to go and live in Entre Ríos…’

‘Oh, yeah, you going to? But you’re not looking too well, son…’

‘No, Dad.’

He wanted to live in a place like that. With all that green, all that water; even the birds were more beautiful than here, with brighter feathers, more colourful beaks. Here everything’s hard, dry, spiky, covered in dust. People were probably friendlier there, even. Here it’s different, here all anyone knows is violence and force.

Brickmakers by Selva Almada is published by Charco Press, priced £9.99.

Secrets of the Last Merfolk is set in Dunlyre, based on the real-life seaside village of Dunure on Scotland’s stunning west coast. Many of the novel’s action scenes take place in the chilly waters of the Firth of Clyde. Here, author Lindsay Littleson writes of how important this landscape is to her.

Secrets of the Last Merfolk

By Lindsay Littleson

Published by Floris Books

At the beginning of Secrets of the Last Merfolk, Finn is furious when he finds out his dad is in Dunlyre to work on a harbour development project, rather than on the holiday he’d been promised. He meets Sage, whose mums are environmental activists, determined to stop the harbour development. Their parents might be on opposing sides, but when Finn sees swimmers in the freezing sea and Sage hears strange singing, the two children begin to work together to investigate the mystery, and they discover merfolk in the Firth!

Despite being in constant danger from a terrifying enemy, the merfolk take their responsibilities very seriously.

‘When we merfolk realised we could live forever, we wondered what we should do with our time. We chose to live our lives caring for the creatures of the shore and the sea.’

However, they despair of the harm humans are doing to the marine environment.

‘They take too many fish from the seas and the dolphins go hungry. They dump rubbish so the seals must swim in dirty water.’

The theme of environmental conservation is of central importance to the story. My brother’s a keen scuba diver and described his dives in the Firth of Clyde. Being as accurate as possible was important to me, even though I was describing fantasy scenes.

The deeper they went, the dimmer and greener the light gleamed, and the stranger the environment became. As Finn swam through a strange, swaying forest of seaweed, he passed spiky pink sea urchins and scuttling hermit crabs. Spotlit in the torch beam, he saw the pale, drifting tentacles of a cluster of anemones.

Sadly, humans have caused terrible damage to the Firth of Clyde. Once, cod, skate and enormous shoals of herring swam in its waters. But a combination of over-fishing and the lifting of a ban on bottom trawling caused stocks of fish to decline alarmingly, and the fishermen began catching shellfish instead. Dredging methods caused further damage, until by the early 2000s the Firth of Clyde was described as becoming a ‘marine desert’.

Lately, some action has been taken to improve the situation, most notably in the waters around Arran. COAST is a community organisation working for the protection and restoration of the marine environment and their work is making a difference to restoring the biodiversity of the Firth.

We can all play our part, by supporting charities like COAST, by taking part in beach clean-ups and by ensuring that we always take our litter home.

This review of Secrets of the Last Merfolk sums up beautifully what I was trying to achieve when I wrote the novel.

‘Secrets of the Last Merfolk is exciting and action packed, and one of our favourite reads of the year. While it explores and embraces legend, it is also a reminder that we should appreciate our reality – and value the enchanting landscapes, wildlife, and people, that we do have.’

Secrets of the Last Merfolk by Lindsay Littleson is published by Floris Books, priced £7.99.

In his book, Phillip Edwards writes beautifully of intimate moments with the birds, the landscape and the weather of the saltmarshes in the west of England. His love of this area shines through in every page.

Extract taken from At the Very End of the Road

By Phillip Edwards

Published by Whittles

Slowly the wind diminishes. Clouds begin to break. Greyness sloughs from the landscape. Sunlight paints colours in dazzling saturation – skeletal trees russet-brown, river leaden, saltmarsh neon-green, lagoons deep ultramarine, reeds bleached ochre, the mud a rich umber. The sea turns steely-blue. Flocks of shelduck shine against the wet silvery shore. A flock of dunlin land along the edge of the dark tide. Their white bodies gleam like a string of pearls on a jeweller’s brown display cushion. Abruptly they levitate again, misting the air, almost motionless, drifting on the wind, passing high over the point to the river, then slowly precipitating into denser sinuous lines that oscillate and dive, disappearing against the dark backdrop of the fields and trees of the far bank, before rising again like wisps of smoke, away to decorate some other stretch of shore. From the sorcery of the sky, a rainbow blooms over the eastern hills. Short and squat, swallowed by the dark clouds above, it refuses to be extinguished and its truncated form glows brightly in its moment of glory before succumbing to the inevitable, to be devoured by the cloud. Yet the rainbow is not done, and as the showers and light shift again, sharpening still further the colours of the land, another rises phoenix-like in its place, flaring into a full arch, polished by the rain, glowing for its ephemeral moment of prismatic perfection, then withering slowly as it too fades into the trails of the storm. Seaward, still far out in the bay, those chameleons of light, the kittiwakes, are now dark grey against the ice-blue sky and shining sea as they journey back to the open ocean.

The top of a neap tide is turning; the mud that has remained above the brown waves is full of waders busy feeding or standing roosting, the sea sprinkled white with shelduck. Tension suddenly courses through the flocks, heads turning, necks craning. A peregrine sweeps around the point pushing a wave of wigeon seaward. She is a female, hatched this year but now large and heavy and sleek, gleaming bronze in the low late autumn light, muscles rippling rhythmically as they power her wings. Waders spasm upward, the beach clearing in a moment as if some giant unseen broom has pushed away unwanted dust from a floor. She swings low across the beach, spreading her wings and tail, arcing lazily upwards over the sea, her dark-streaked white underparts glinting briefly in the sun. Wings sleeked once more, she dives back along the water’s edge, gaining rapidly on a great black-backed gull, its white plumage still muddied with immature feathers as if it has spent too long dipped in the dirty sea. She rapidly overhauls the lumbering gull but slows as she passes over it, slipping easily to one side as the gull turns its heavy beak and lunges at her, as if irritated by the impudence of her proximity. She turns away and replicates the entire manoeuvre, hanging briefly over the gull with just enough distance to evade the danger held within the swipe of its beak. She retires once more. When she comes again, she does so from a different trajectory, flatter, slower, her wings more bowed and ballooning, enveloping the air beneath them. The gull ignores her this time with utter disdain, bored like a parent with a fractious child, for it is secure now in the knowledge that its much smaller tormentor is not hunting but simply using it for target practice, learning how to approach in different ways at different speeds and different angles. Twice more she comes in slowly and just above the gull, hanging briefly over it at the perigee of her orbit, then angling away. By the final time, the gull has moved too far from the point, and she heads back low along the now empty beach and lands on the opalescent mud. She preens.

Ten minutes later she lifts into the light wind and heads seaward. Shelducks paddle heavily through the waves to avoid her. She swings slowly into wind and closes over one, coming to the point of a stall directly above it, talons extended. She drops gently. The shelduck crash-dives in a shower of spray as if surprised to have been picked as a target, and the peregrine bends away, flapping leisurely, gaining height smoothly. She turns again, wings fully outstretched, and curves back in a shallow glide. The shelduck flock is now fully alert and scatters quickly ahead of her approach, but she is fast and comes quickly above another one, adjusting her attitude rapidly to hang just above it. It too dives to avoid her unwanted attention. But this time she stays on the cusp of a hover, waiting for its re-emergence nearby, angling quickly back towards it, then sharply upwards as the terrified shelduck dives again. She climbs steadily to a hundred feet, shakes herself in flight, sending rolls of ruffled feathers down her body like a dog shaking water from its coat, and glides back towards the mud, practising the same hovering manoeuvre briefly over a startled cormorant drying its unwaterproofed wings at the edge of the shore, as if she just cannot resist.

She rests and preens for another ten minutes and watches nine grey plovers that have the temerity to land and feed nearby. Then she opens her wings and flickers seawards again, but this time with purpose. She remains low, ignoring the shelduck flocks even as she cuts a swathe through them, intent instead on the flocks of wigeon swimming slightly further out. She angles in across the wind and comes to a hover, stationary on motionless wings angled finely enough to let the wind hold her momentarily, legs extended. The flock scatters in a storm of spray. Ducks that never dive, dive.

Anything to avoid the horror. The peregrine rises and banks steeply on a tight axis and approaches again, slowly and from a shallower angle, closer to the water, her silhouette now less distinctive to the wigeon but her presence just as terrifying. And this time all the morning’s practising generates the outcome she was trying to elicit: the wigeon panic and take flight. Instantaneously she climbs on straining wings, forcing the air away behind her as she wrenches herself upward. The wigeon flock coalesces, tightening even as it leaves the water, the white on the males’ upper wings flashing like distress beacons in the weak sunshine. Briefly, the flock diverges from the rising falcon, but as she rolls out of her climb and dives, that distance closes like a rifle’s recoil. She plunges through the flock, black talons grasping, then slows and turns but holds no prey. The wigeon have jinked away at the very last moment and now the gap between flock and falcon widens progressively. She returns shoreward, her loose flight seemingly carrying an air of dejection that failure inevitably accrues, yet only through failure comes knowledge and while her youth means she still has much to learn, the morning’s experience indicates that she learns fast. She will go hungry today, but that will only sharpen her schooling. The wigeon will soon face a formidable adversary.

At the Very End of the Road by Phillip Edwards is published by Whittles, priced £16.99

Bella Caledonia is a website that publishes essays, articles and reviews on Scottish political, social and cultural issues. Founder and editor Mike Small has put together an anthology of memorable contributions, and we share Mairi McFadyen’s essay here.

Essay taken from Bella Caledonia: An Anthology

Edited by Mike Small

Published by Leamington Books

The Art of Living Together

Mairi McFadyen

This month I was at The Ceilidh Place in Ullapool for the annual adult Fèis Rois gathering, a three-day festival of tuition in traditional music, song, dance, Gaelic language and culture alongside fringe events, gigs and late-night cèilidh sessions in pubs all over the north west’s cultural capital. There is such a spirit of community here. For many, this is a chance not only to meet friends old and new, but to learn from the great tradition bearers – such as fiddler Aonghas Grant or Gaelic singers Rona Lightfoot and Cathy Ann MacPhee.

This year the Fèis also welcomed a group of singers and musicians from Brittany, who threw a fest noz into the mix; two blind music students from the National Academy of Music in Bucharest and a young musician who is working hard to raise awareness of autism. Music has such an incredible power to connect, to bring people together. The whole weekend was a life-affirming and hopeful reminder of what is important to hold on to in the face of it all.With the relentless daily news cycle headlining the triple crisis of climate change, mass extinction and inequality alongside escalating trends of populism, isolation, alienation, uncertainty and disconnection, creating spaces for connection and conviviality is more vital now than ever.

A particularly special moment was the performance of the ‘Kin and the Community’ project Sgeulachd Phàdruig Mhoireasdain – one in a series of short films bringing to life audio archive recordings alongside newly composed music as a soundtrack to a life story. In this instance, we learned of the life of musician Pàdruig Morrison’s own grandfather, Peter (Pàdruig) Morrison, a man who survived the first world war and lived as a crofter in Grimsay, North Uist.The audience witnessed past and present fuse together as Pàdruig and friends accompanied his forebears in real time, unlocking layers of memory and meaning and inviting us to reflect on who we are and where we come from. Inspired by and created under the guidance of fiddler and composer Duncan Chisholm, this work of creative ethnology is a moving reminder of what it is to be human.

We live in a society that has forgotten to value what it is to be human, in a world where far too many people get left behind. Our economy cares not for localities, cultures, ways of life or the cohesion of kin and community.The pervasive growth-at-all-costs model – upheld by all of the main political parties and mainstream media – is so narrowly focused on the pursuit of profit, productivity and measuring GDP that it fails to count the damage it wreaks on the environment or the health, well-being and dignity of its citizens.

What can we do to resist and reclaim our lives, our communities, our planet?

Reclaiming the Commons

Across the globe, the commons movement is growing and reclaiming hopeful alternatives to the dispiriting status quo of market economics, challenging the deep pathologies of contemporary capitalism and suggesting cooperative, egalitarian and participatory alternatives.

Deeply rooted in human history, it is difficult to settle on a single definition of the commons that covers its broad potential for social, economic, cultural and political change. The commons includes natural resources – land, water, air, forests, food, minerals, energy. It also encompasses our cultural inheritance – the traditions, practices and shared knowledge that make society possible and life meaningful. Commoning is the lived expression of conviviality, understood as the ‘art of living together’ (con-vivere). Put most simply, perhaps, the commons is that which we all share that should be nurtured in the present and passed on, undiminished, to future generations.

The movement to name and reclaim the commons has roots in the struggle of English commoners against the ‘enclosures’ of the 15th, 16th & 17th centuries by the rising class of gentry who expropriated common land for their private use; and later, in both Lowland and Highland Scotland, the dispossession of the Clearances. These enclosures severed a deep connection to the land and destroyed local cultures, paving the way for the industrialisation, colonisation and globalisation of the modern world.

In the 21st century, it is not just land and resources that have been enclosed by capitalism, but almost all aspects of life itself. The modern tendency towards turning relationships into services, commons into commodities, human into machine has been described by commons scholar David Bollier as ‘the great invisible tragedy of our time.’ The ‘new enclosure’ can be seen in the patenting of genes, lifeforms, medicines and seed crops, the use of copyright to lock up creativity and culture, academic knowledge behind paywalls and attempts to transform the open internet into a closed, proprietary marketplace, shrinking the public domain of ideas, among many other examples.

The endgame of this process is the enclosure of the mind and the cooption of dissent.The absolute triumph of this system is demonstrated by the fact that so many of us have lost the ability to imagine our way out. As Naomi Klein has written, we are ‘locked in, politically, physically and culturally’ to the world that capital has made. We are up against the formidable capacity of global capitalist and colonial systems of power to enclose our sense of the possible.

Connection and Conviviality

Despite the rapid encroachment by capitalism on the commons, much of what we value in terms of quality of life is still created outside the spaces of economic exchange, through the voluntary association of friends, neighbours and citizens. Convivial co-operation is very much alive in scattered enclaves and in communities – in the home, the library, local clubs, community gardens, community land trusts, or simply in an open-mic night, cèilidh or pub session. These are the places and spaces where the impulse and catalyst to strike and kindle sparks of change, creativity and transformation are to be found.

The carrying stream of traditional music is a cultural commons. Every song, pipe march, slow air, jig or reel has its own story to tell, connected to the language, histories and memories of people, places and lives lived. At its heart, traditional music is a shared activity, a community practice, drawing on wells of deep communal and collective memory, passing from previous generations to the curiosity, ingenuity and dexterity of the next. The tradition has been created by many hands; first in the minds of individuals, but often reshaped – altered simply through the human process of forgetfulness or given new life by those with a desire to innovate. There is the spirit of the commons too among those who are generous with their passion and talents, willing to share and pass on their knowledge through playing and teaching.

This music does not represent some parochial caricature of a bygone age, but rather a living, breathing culture that is as contemporary today as it ever was. Rooted in place, it has a life force and an energy that demands to be reshaped, to continue, to be passed on.

Traditional music has always resisted mainstream commodification, despite the success of the ‘creative industries’ in packaging this music as an export brand for global consumption. While the brand-driven individualism of neoliberal economics demands of all artists to be professional entrepreneurs – and while some may enjoy or benefit from this situation in financial terms – many more sit precariously and uncomfortably within such a dehumanising ideology.

It is important to name it too: the neoliberal ideology and discourse of the creative industries belongs to the same story of economic growth, and is therefore enmeshed and implicated in the wider process of climate breakdown. It’s all connected.

This is not an argument to get rid of money or markets; neither is this an argument for an economics of scarcity or against regeneration. This is an argument for transforming and releasing ourselves from the grip and structures of contemporary neoliberal capitalism-as-we-know-it. Our very survival as a species depends on it.

Capitalism moves fast. We need time to slow down, reflect, remember, resist and make space for what really matters. When we slow down, our experience of being human swells. Our sense of possibility augments and swells with it. Paulo Freire wrote that it is our vocation to become more fully human. What he means by this is that we must move from existing as human objects to be acted upon towards becoming subjects who think and act with critical consciousness, liberating our imaginations and transforming the world.

We might think of reclaiming the commons as reclaiming our past and our future, reclaiming what it means to be human, to be alive. If, somehow, we are able to come together to confront and overcome the desperate challenges that lie ahead, we might just find a world far richer in possibilities than the one we leave behind.

Bella Caledonia: An Anthology edited by Mike Small is published by Leamington Books, priced £9.99.

Deborah Bird Rose was a world-renowned anthropologist and leading figure in environmental humanities. Shimmer was her much-anticipated final book and reflects on her etho-ethnographical fieldwork with flying fox scientists, conservationists and Australian Aboriginal communities.

Extract taken from Shimmer: Flying Fox Exuberance in Worlds of Peril

By Deborah Bird Rose

Published by Edinburgh University Press

The fact is that we will never know what it is like to be flying-fox, or a tree. As the ecologist Frank Egler famously, and wisely, put it: ‘ecosystems may not only be more complex than we think, they may be more complex than we can think’. What is true of ecosystems is true at other scales. Flying-foxes individually are more complex than we think, and complex in ways beyond our thought. Their ethos includes their many social skills and cultural repertoires. And yet we also share glimpses of worlds, actions and connectivities. The mutualisms that sustain all of us are not obscure, and new information is always emerging.

Responsibilities: One of the most devastating effects of the animal-human binary has been the rejection of the idea that we have ethical responsibilities towards other creatures. Although in recent years this binary increasingly has been undermined in favour of connectivities across borders of difference, there is still a strong social/political ‘common sense’ position that puts human interests above all others.

And yet, the call into responsibility is not dependent on the specifics of any given creature, its species, its usefulness, its cuteness; rather it is enough to know that the call is there. But at the same time, responses must always be appropriate to the needs of others, as best we can understand them. In writing, thinking and working across the boundaries of species we find ourselves face to face with both mystery and familiarity. Others are not replicas of us, and at times the gap is incommensurable. And yet, we are all kin within the family of life on Earth. This insight into kinship was the ‘real scandal’ of Darwin’s work; it reveals the connectivities that the animal-human binary sought to conceal. When we live ethically, we become participants in flows of mutual life-giving. Ethics arising in the actual conditions of life cannot be abstract and universal, nor can they constitute a closed system. By the same logic, ethical writing requires openness both to the peril and to the joy of others. There are words of alarm – necessary and passionate, aiming to amplify ethical claims. Equally there is praise and celebration – for the lives of others, their passion and their gifts. Even as I raise my voice against violence, I focus my study on the beauty of flying-foxes’ ways of living: their high-flying verve, their joyful labour awash in pollen and nectar, their travels and attachments to home place, and their intensely social lives.

Multispecies ethnography: New understandings of connectivity enable new fields of research and writing that embrace affirmations of participation. One of the great anthropologists of the Anthropocene, Anna Tsing, evokes the excitement of this gripping moment:

There is a new science studies afoot . . . and its key characteristic is multispecies love. Unlike earlier forms of science studies . . . it allows something new: passionate immersion in the lives of the nonhumans being studied. Once such immersion was allowed only to natural scientists, and mainly on the condition that the love didn’t show. The critical intervention is that it allows learnedness in natural science and all the tools of the arts to convey passionate connection.

Deeply attentive to the lives of nonhumans, this new research is committed to engaging with diversity amongst humans as well. Multispecies ethnography, articulated initially by Eben Kirksey and Stefan Helmreich, is only possible because so many boundaries are now understood to be porous. Wide-ranging, open and inclusive modes of research cultivate arts of attentiveness. Multispecies research brings us into encounter with ‘a lively world in which being is always becoming, [and] becoming is always becoming-with’.

You are not alone: The West’s former view that all that was not human was simply mindless matter seems barely credible anymore. And yet, a huge shift is required when we consider that our human lives are situated in vast realms of sentience. The Australian Aboriginal philosopher Mary Graham states that one of the basic premises of the Aboriginal worldview is: ‘You are not alone in the world.’ And herein lies a powerful, perhaps alarming, challenge. In the midst of all this sentience, there is no hiding. The consequences of human action are not borne by mindless machines but by living beings, many of whom are conscious of their own lives and of the lives of others. And so, given that almost all the factors driving two Australian flying-foxes to the edge of extinction are biocultural (and include human and nonhuman actions), we bear responsibilities that are witnessed not only by other humans but by other living (and perhaps non-living) beings as well. We are called, therefore, into participation and intra-action. It is true that, for better or worse, we always participate in life’s flow.

Shimmer: Flying Fox Exuberance in Worlds of Peril by Deborah Bird Rose is published by Edinburgh University Press, priced £14.99.

Mark Mechan’s Welly Boot Broth is a warm, charming picture book showing the fun and imagination in growing your own vegetables. We caught up with Mark to chat to him about his book.

Welly Boot Broth

By Mark Mechan

Published by Waverley Books

Congratulations on the publication of Welly Boot Broth – it’s such a lovely book. Can you tell us a little bit about it?

Thank you very much. It’s the story of a little boy, Elliot, whose Dad encourages him to ‘grow his own broth’ by planting vegetables in their garden. We follow Elliot as he ‘helps’ to dig, sow, weed … and fend off pests which are many fold in the garden. Elliot meanwhile indulges his love of digging deep holes, and letting his imagination run away with what he finds. The book is less ‘how to garden’ and more ‘give it a go and see what can happen or go wrong’. My publisher Waverley Books were as keen as I was to retain the flavour of Scottishness that had characterised my first book, Tumshie.

I used to come home from primary school for my lunch — often a bowl of tinned tomato, (which by the way is still the ultimate comfort food), with rolled up balls of doughy white bread dropped into it … bliss. But mum also made the most delicious home-made broths: chicken soup, lentil soup, vegetable broth. So I’m trying not to be judgemental (and god knows I still eat a lot of unhealthy stuff myself), but when you’re responsible for putting decent food in your own kids’ mouths, you start to weigh up other responsibilities. So, that first spread showing a frowning Dad opening a tin of tomato soup for Elliot hopefully will chime with parents who might find themselves in that tricky area between wanting to provide something wholesome for their kids, and finding literally anything at all that they will eat.

The book has a light touch theme about sustainable living and the wonder of growing your own veg. Do you think it’s important to teach kids as well as entertain them?

Oh yes, and of course the trick is – as you say – to do it with a light touch. Growing your own can teach food comes from, patience and nurture, the ability to think and plan long term, and the rewards of creating something from almost nothing. I feel that kids instinctively know if they’re being preached at and I want to try to avoid being too heavy handed. This story and Tumshie both come from personal experience, something my family and I have done, rather than an idea or a message that I wanted to mould a story around.

The other thing is that I just wanted to get across how much fun gardening can be. It’s a long game, waiting for your hard work at the start of the year to bear fruit (or veg) months later. For very small kids that’s not really engaging – it’s like waiting months for Christmas to finally arrive. But the enjoyment for wee ones is in the digging, getting dirty, finding worms, sowing seeds; then the daily caring for their wee plot — and the thrill of seeing the first sprouting shoots is really something exciting (well, I think so…). And eventually pulling a carrot from the ground, smelling it, tasting it – is even more exciting.

You have worked in publishing for a long time designing book jackets. What made you decide to enter the world of children’s picture books?

When our first two kids Charlie and Lily were really wee, I toyed with the idea of creating a book just for them. I insisted that we had a troll living under the floorboards of our house, and I thought it would be a fun project to create a story book around that. But young parents don’t really have that much time to burn, so I let that one slide. By the time our third, Elliot, was at school, our daily walk to his school gates would be chit-chat about what he would be dressing as for Halloween (which involved him coming up with outlandish ideas and me setting myself the challenge of whether they could feasibly be made out of corrugated cardboard). Between the two of us we cooked up the idea of a book, starring Elliot of course (and ‘Dad’, a younger version of me), about traditional Scottish Halloween — the centrepiece of which for me had always been the Turnip Lantern. I would complain to Elliot how no-one seemed to carve a tumshie any more, and that costumes were always bought rather than cobbled together at home. My bent for nostalgia sparked the book into life, although by the time I had pitched the idea to Waverley, created it, and Tumshie was finally published, Elliot was halfway through high school. So — a long gestation period. A bit like growing vegetables.

How do you approach illustration? What are you keen to get across visually?

What I try to do most is to create a depth of texture and colour that feels natural. It’s one of the reasons I use charcoal to draw with. The strokes are full of accidental richness that is hard to replicate in any other way. Meaning, I could have drawn it all digitally but that is just not so much fun. A charcoal sketch also tends to build up a little microclimate of smudges, fingerprints, rubbings out … ghosts of previous strokes that weren’t quite right. It brings the drawing a character that I really enjoy. Much of that texture isn’t always apparent in the final printed version, but the truth of the work is in its creation as much as its final appearance.

I’m pretty eclectic when it comes to design and illustration, but for my picture books I‘ve stuck to traditional drawings with charcoal on paper, which are scanned and then coloured digitally. I’ll draw the elements separately — people, backgrounds, objects — and combining them digitally to create the spread helps me retain a flexibility of composition that I wouldn’t otherwise have.

I’m from a generation that crossed the borderline between ‘traditional’ art techniques and the beginning of digital illustration. I was studying drawing and painting at Duncan of Jordanstone in Dundee when Photoshop was born, and moved into graphic design as a career when it was already becoming the industry standard for publishing houses using desktop publishing. So I’ll never lose my love of drawing on paper, the immediacy of it, and the physicality of it. Digital drawing and painting is incredibly fun, diverse and almost infinitely flexible, which I love too, so I’m happy to have a foot in both camps.

Thankfully, there are no wellies in the soup in the book! What’s your favourite soup to make and eat?

I love to make a proper borscht, which takes me two days — involving the roasting of beef bones for the bone broth. I like the earthniness of the beetroot, and the tang of the sour cream to finish it. But the soup that I’m most frequently asked to make is a mushroom soup, from a Rose Elliot recipe. It’s creamy, with a spike of paprika and a cheeky dash of sherry. I’ve never grown mushrooms though, so that soup didn’t make it into Welly Boot Broth.

Are you a keen gardener yourself?

Yes I love gardening, though I’m no expert. I remember my Grandpa popping pea pods for me in his allotment — Anderson shelter an’ all —and so I always raise peas in my garden now. They are so much fun to watch grow. I was very lucky to have inherited a garden with a vegetable plot from the woman who lived in my house before we bought it, about 20 years ago. (Mrs Kerr in Welly Boot Broth was named after her – my own private tribute). I spent this past summer digging a pond, landscaping and planting flowers which my wife Alison would constantly mail order for me. And I still have some veg in the ground to be pulled. Soup yet to be made!

What other illustrated books have caught your eye recently?

I can’t stop poring over mid-century children’s books that I find online. Graphically they amaze and inspire me. More recently though a book that I’ve picked up amongst the hundreds of stunning-looking books on show is the illustrated version of The House by the Lake by Thomas Harding. It’s illustrated by Britta Teckentraup. It’s such a beautiful book, and the layering of the house’s history is reflected in her gorgeous artwork.

Welly Boot Broth by Mark Mechan is published by Waverley Books, priced £7.99.

Martin Moran lived life in the mountains to the full. He climbed and guided in the Alps, Norway, the Himalayas, and in the mountains of Scotland, and his memoir describes his climbing experiences with a deep awe and respect.

Extract taken from Higher Ground: A Mountain Guide’s Life

By Martin Moran

Published by Sandstone Press

‘Only a hill; but all of life to me

Up there between the sunset and the sea.’

Geoffrey Winthrop Young

I never especially wanted to be a mountain guide, but it was the hills that opened my soul to the wonders of existence. By the age of eight they had become a major part of my dreams and imaginings. I was born into an aspirational household that was making the post-war transition from working to middle-class status. Neither of my parents had the least inkling towards outdoor adventure. My mother was a dreamer, but was tied by the conventions of a housewife’s life. My father was provider and disciplinarian with scant time to spare from his career as financial accountant to a company in Wallsend on North Tyneside. Like so many of their generation both Mum and Dad sacrificed personal indulgence to give my brother and me the best possible starts in life, but their greatest contribution to my cause was unwitting.

Both parents had distaste for the conventional seaside holiday of the 1960s, and instead we were taken on touring trips in the Lake District and Scottish Highlands. My eyes were first opened to the hills through the back windows of a Vauxhall Victor. On Kirkstone Pass I saw grim crags rearing up into the mists on Red Screes. In Glen Lyon I marvelled at pencilled torrents which plunged from hidden heights. I urgently needed to find out what was where, to define and contain the world, and so became obsessed with maps. I accumulated a collection of Ordnance Survey One Inch sheets and became a devotee of Wainwright’s guidebooks. The strange Gaelic names of the Highlands – Sgurr nan Clach Geala, An Teallach, Bidean nam Bian – evoked a mix of fear and enticement.

Soon I was scampering up hillocks and hummocks during Sunday picnics in the Cheviot Hills. Langlee Crags and Humbleton Hill briefly meant all the world to me, but by now I had found the mountain bookshelf in North Shields library and my horizon widened. On a family drive to Devon the billowing masses of summer cumulus became my own Himalaya, every cloud cap a new and unfathomable summit, and with excitement came fear. One night in bed my imagination passed from the hills to the whole of the Earth and up to the sky. The stars stretched into a yawning and terrible abyss. Suddenly I sensed the ultimate truth and in a spasm of panic rushed downstairs to the arms of my mother. I now knew that a search for the absolute was futile, but I was not deterred from the quest. From fell-walks and camps to rock faces and bivouacs, the hills gave me solace and inspiration through my teenage years. All else in life seemed dull by compare and I won revelations of a life beyond the plain.

*

By December 1978 I was married and living in Sheffield. So far the magic of Scottish winter mountaineering had eluded me. I was steeped in the works of Bill Murray and the legends of Tom Patey, Jimmy Marshall and Robin Smith. The sublime experiences described by Murray in Mountaineering in Scotland convinced me that it was in this genre that the true force lay. Yet my previous trips north had all ended in storm or retreat through want of courage.

Lacking a ready partner I resolved to make a weekend visit to the Cairngorms alone and absconded from a tedious accountancy audit in the early afternoon. We owned a seventeen-year-old Ford Anglia, inherited from my late grandfather. I dropped Joy, my wife, with her family in Durham and drove north through torrential rain, battling self-doubt and loneliness. The 350-mile journey seemed interminable but the rain petered out to be replaced by snow showers, which fired mesmerising volleys of white daggers across the headlight beams. On the climb from Glen Shee to the Cairnwell thick banks of powder snow defeated the car. I parked and bedded down on the back seat, my mood morose but still determined.

A snow-plough appeared at 7.00 am and, tucking in behind, I surmounted the pass in triumph. My perseverance had paid off. Remembering the joys of a summer crossing as a fifteen-year-old Scout I was drawn to the Cairn Toul-Braeriach massif. The hike up Glen Dee was a soulless trudge and the hills were shrouded behind the veils of falling snow, but I kept my head down and climbed Cairn Toul from Corrour bothy without a stop. On the summit the visibility was less than twenty-five metres, so I took a direct descent past Lochan Uaine and cramponned delicately down the frozen water-slide of its outflow stream. Just before darkness I found the squat stone-clad Garbh Choire bothy, and settled in for the sixteen-hour night. Tomorrow’s likely outcome would be another dull trudge back to the car and yet another disappointment, but at least I was secure and warm.

In such expectancy I overslept my alarm by an hour. The bothy door opened to a morning of absolute clarity. The mountains shone under a white blanket of fresh snow. I couldn’t get packed quick enough. The snow was dry and aerated making the 600m climb to Braeriach an exhausting struggle, but what recompense there was in the views of the snow-plastered corrie walls around me. On reaching the summit, my sight ranged westward across the upper Spey valley to the white rump of Ben Nevis, which sailed on the skyline sixty miles away.

Anxious to squeeze every moment of pleasure out of this precious day, I ploughed down to the Pools of Dee in the jaws of the Lairig Ghru, straight up the east side, and on to Ben Macdui. Already the sun was slipping from my grasp. I pounded over the summit and descended towards the Luibeg Burn. Midday’s glare faded to a pale pink alpenglow, which flushed the high tops for a magical half-hour until the heavens turned to indigo, leaving only the western horizons with a fringe of light. The immensity of the vision moved me close to tears. A blanket of freezing fog gathered in the glen as I jogged down the icy track. Once more I saw the Universe for what it is, infinite and pitiless; I could feel the sting of death in the barren frost, and yet was utterly happy. The paradox is inexplicable. Back at Linn of Dee the Ford Anglia’s engine fired first time and a wind of elation carried me home.

Higher Ground: A Mountain Guide’s Life by Martin Moran is published by Sandstone Press, priced £11.99.

This month leaders from around the world landed on our shores for COP26 and with the eyes of the earth upon us, our thoughts, more than ever, turned to the importance of celebrating and protecting the natural world.

At Floris Books HQ they believe that it’s vital to plant the seed early and love shaking their pompoms to champion their books that do just that. In this rousing roundup, we share the best of their inspiring and beautiful picture books which help encourage wee ones to grow a love and appreciation for nature.

FROM SUNNY, SUSTAINABLE DAYS

Spin a Scarf of Sunshine – Dawn Casey and Stila Lim

Nari lives on a small farm with hens and bees and apple trees, and cares for a little lamb of her own. The seasons turn and Nari’s lamb grows into a fine sheep with a fleece that is ready to shear. Nari and her family use traditional skills to transform the fleece into a cosy scarf, as they shear, spin, dye and knit. But as Nari grows older her beloved scarf becomes tattered – it is ready to be recycled into compost for the farm with the help of some friendly worms.

Stila Lim’s luminous illustrations will inspire children and adults alike to explore the simple beauty around them and connect them to the idea of sustainable living and knowing where our clothing comes from.

Listen to author Dawn Casey read an extract.

Learn how to knit your own wee lamb on our blog!

TO ILLUMINATING, EVOCATIVE NIGHTS

The Night Walk – Marie Dorléans

Mama opened our bedroom door. “Come on, you two,” she whispered. “We need to go now, to get there on time.”

Excited, the sleepy family step outside into a beautiful summer evening. They’ve entered a night-time world, quiet and shadowy, filled with fresh smells and amazing sights. Is this what they miss when they’re asleep?

Translated from French, the original edition of this book won the prestigious Prix Landerneau in the best children’s picture book category. It shares the dreamy story of a family’s exciting journey through the night. Beautiful and evocative, this stunning book celebrates the importance of family time and the awe-inspiring power of the natural world.

Check out the video trailer here.

AND MESMORISING STARRY SKIES

The Depth of the Lake and the Height of the Sky – Kim Jihyun

Finally, and without a single word uttered, Kim Jihyun’s wordless wonder The Depth of the Lake and the Height of the Sky tells the heartfelt and uplifting story of a child’s independent discovery of the natural world.

A boy and his dog set off from his grandparents’ home in the countryside to explore. At each bend in the trail the boy discovers something astounding, from towering trees to a still, silent lake. He can’t resist diving down, down into the cool water and greeting the fish below. Then later, when boy and dog have been warmed by the gentle sunshine, they wander back, contentedly, to their family. But before they go to sleep, nature gives them one last dazzling show: they look up, up to a night sky awash with stars.

Take a sneak peek inside the book and marvel at some of the incredible illustrations.

Eager from more? Discover all of the beautiful Floris picture books here.

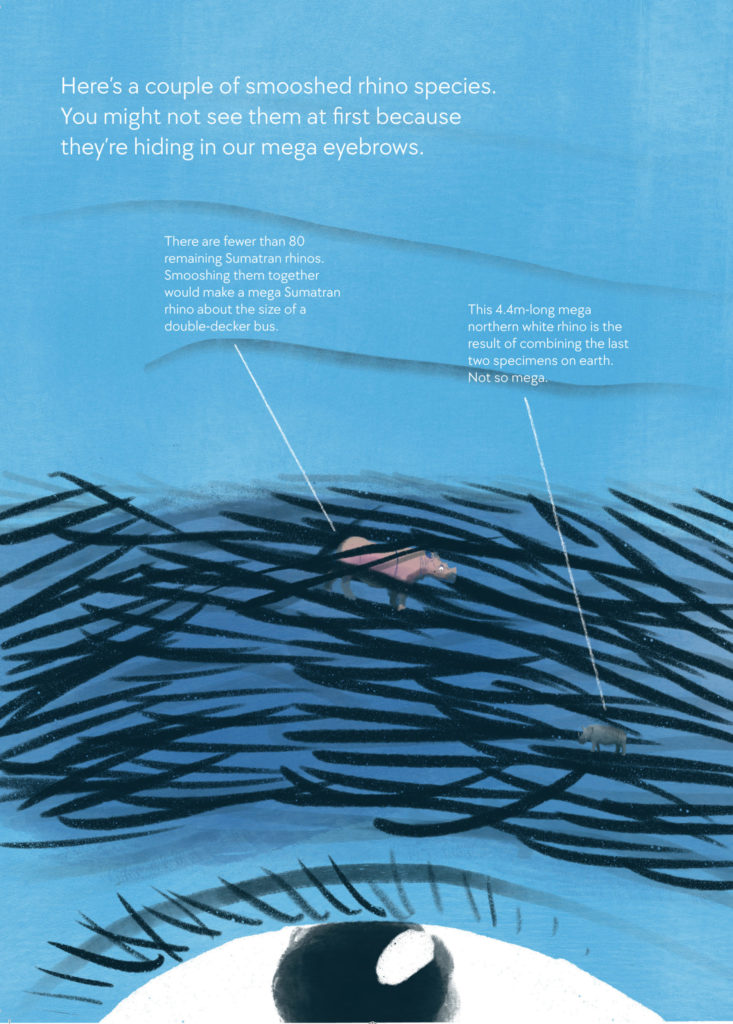

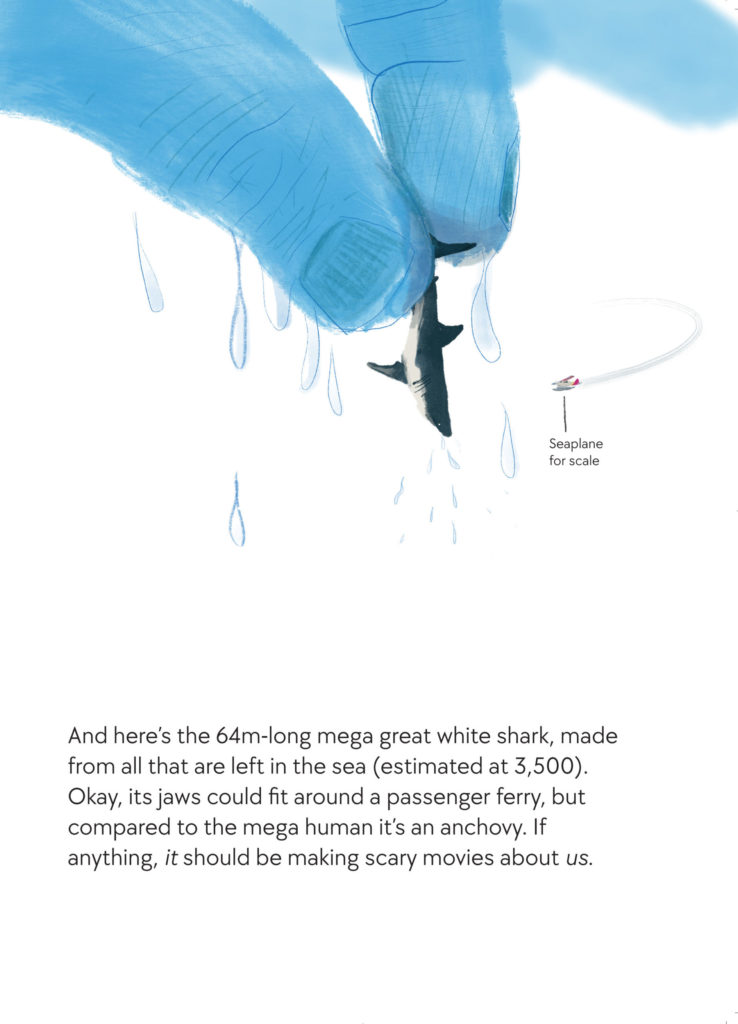

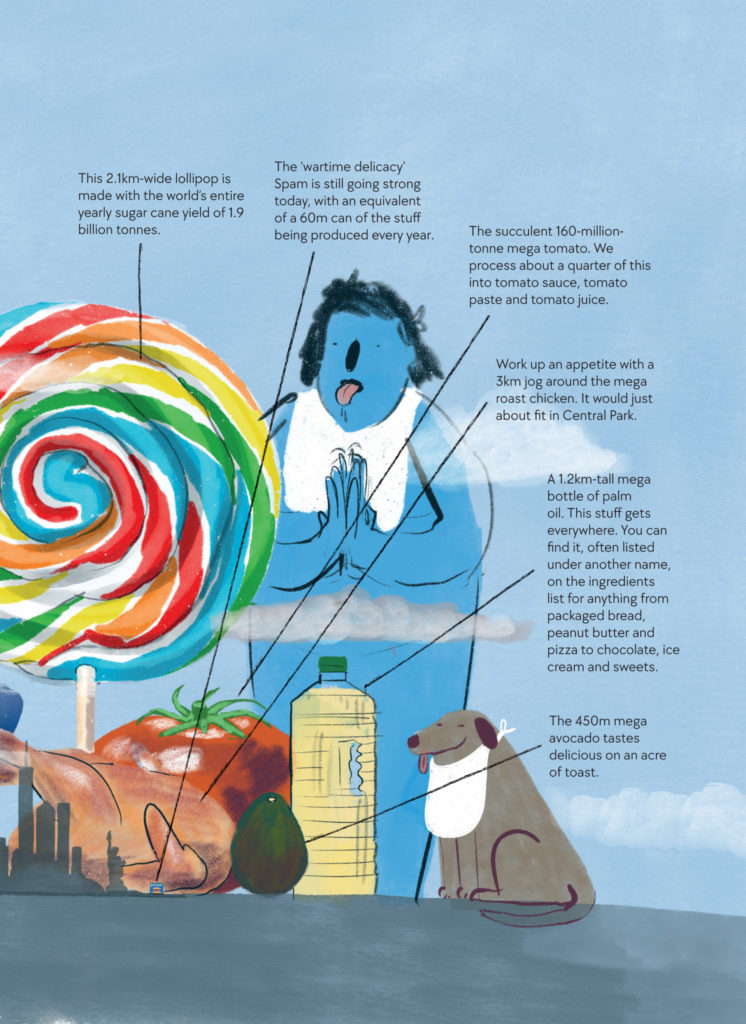

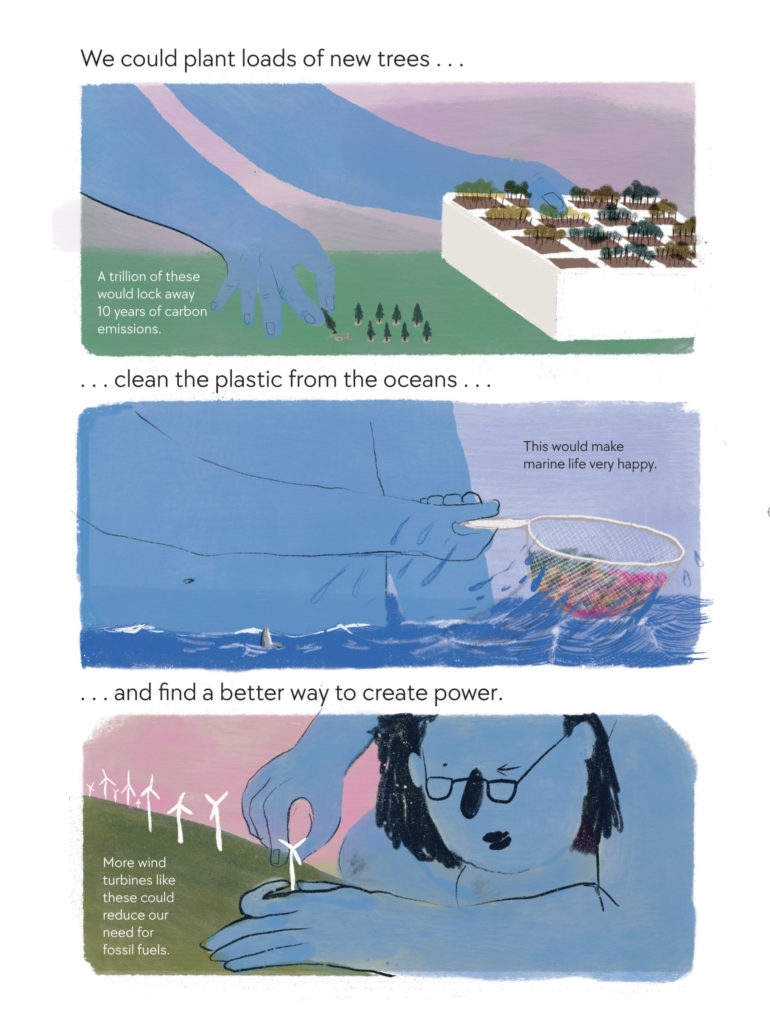

The Biggest Footprint is a fascinating and gorgeous book for children. By ‘smooshing’ all the humans on earth into one giant, Rob and Tom Sears show how our actions affect the planet and what we can do to make sure we can restore our earth to a more natural state, and not treat it as a resource to plunder. It will make you laugh and think, and we couldn’t wait to show you some of its wonderful pages.

The Biggest Footprint

By Rob & Tom Sears

Published by Canongate Books

The Biggest Footprint by Rob & Tom Sears is published by Canongate Books, priced £14.99.

At this time of year, it’s usual to see a celeb memoir or two high in the bestseller list. David Robinson reads two that are well worth a spot on your lists to Santa.

Putting the Rabbit in the Hat: My Autobiography

By Brian Cox

Published by Quercus

Baggage: Tales from A Packed Life

By Alan Cumming

Published by Canongate

HOW do you become a star? How do you fascinate, cast an eclipsing spell, persuade the audience that whatever you are making up is really true? Is it all just a matter of getting the biggest, showiest, roles at the right time? Can it be taught and if so how?

These questions lie at the heart of two memoirs published this month – by, as it happens, two Scots who best know the answers. Losing self-consciousness is, Alan Cumming and Brian Cox concur, the key to great acting. Yet as both their books show, their childhoods gave them an awful lot to be self-conscious about.

For Cox, growing up in Dundee’s Brown Constable Street was carefree until he was eight. His debt-laden father’s death plunged the family into poverty and his mother into mental illness (she was hospitalised for over a year when he was ten). Yet Cox has been a star for so long, and been interviewed so often, that much of this is already widely known. So what does his memoir, Putting the Rabbit in the Hat, tell us that isn’t?

First of all, because he clearly hasn’t used a ghostwriter, we get a sense of how his mind works. This is no bland chronological, punch-pulling narrative, and instead hops back and forth across decades. The chapter on his schooldays, for example, leaps ahead to 2010 to make a good point about the naturalness of child actors, then we’re back to Cox daydreaming his way through secondary modern in 1960, and to his love of comics, in particular the Classics Illustrated series. Within a few lines, we’re fast-forwarded to 1997, when he’s filming The Boxer in Northern Ireland and watching its star, Daniel Day-Lewis, carry method acting to extremes. Why? Because twenty years later Day-Lewis gave up acting to become a cobbler and the Classics Illustrated version of A Tale of Two Cities reminded him of that.

This may be convoluted, but it rings true: big themes (here, method acting) often are triggered by the smallest details, and sometimes these can be fascinating. His parents met, he explains, because both their fathers died around the same time. In 1927, that meant three months of wearing a black armband and not socialising. If you wanted to go to a dance, for example, you had to leave town (Dundee) and go to a distant dancehall (Montrose) – which is what they both did, and where they first met.

Yet none of this gets in the way of Cox showing the key turning points in his life, like when he first watched Nicol Williamson at Dundee Rep and discovered the meaning of ‘theatrical presence’ and how a good actor ‘can displace the air’. He’d already got a hint of what was possible from cinema: Spencer Tracey, his mother’s favourite actor, was his too. Studying acting at LAMDA in the early 1960s, a host of other greats soon followed: Olivier, O’Toole, Glenda Jackson, Maggie Smith. All the time, he was watching and learning, catching them in rehearsal as well as performance, just as (fast forward again) he has spent the pandemic months catching up on indie cinema.

He was also working out a lot of things for himself. Brown Constable Street had given him a strong personality, but he had to stop it getting in the way of his acting. School didn’t instil an ability to focus, so he had to learn it. Fulton Mackay, a mentor and friend, taught him not to aim at stardom: just being a good actor was ambition enough. From Michael Elliot and Lindsey Anderson, he learnt how much a good director – one who digs deep into the text rather than fussing about lighting or camera angles – can bring to a production. Anderson, in particular, taught him stillness, how to let the audience come to him rather than demanding its attention – all encapsulated in his classic note: ‘Brian, don’t just do something, stand there.’

Put all of that together, and you can see why Cox is the kind of actor he is. Shakespeare, he says, is spot-on in Hamlet’s advice to the players: holding the mirror up to nature means just that: instead of muddying the text with what he calls ‘front foot acting’, actors should just be its conduit. Acting should be about expiation, about allowing the stage magic hinted at in the book’s title to happen: what it’s emphatically not about is surface show.

Cox doesn’t mince his words here. No matter the megawattage of the star involved, if he doesn’t believe in a performance, he’ll say so. Johnny Depp? Overrated. Tarantino? Meretricious. Kevin Spacey? A great talent, but stupid. Michael Caton-Jones? Doesn’t care enough about the script. Ed Norton? ‘A nice lad but a bit of a pain in the arse’. Gary Oldman’s Darkest Hour? ‘A shallow, crowd-pleasing farrago’. Oldman’s portrayal of Churchill, of course, won him the Oscar in 2017, while Cox’s own ‘more honest’ and ‘better researched’ Churchill that same year did not.

Normally, I would put Cox’s reaction down to sour grapes, but he makes a plausible case for his own film being better. And because of the candour he shows him in other judgments (not least his self-criticism over his failings as a father and husband), I’m inclined to believe him. Actorly forthrightness on such a scale is, frankly, rather refreshing. Where else, for example, can you expect to come across a chapter which opens like this: ‘To explain what I mean about “doing a schtick”, it’s worth looking at the example of Sir Ian McKellen’?

For all his many triumphs – not least, right now, his towering, Golden Globe-winning lead role as media mogul Logan Roy in Succession – he admits that he never has found closure (‘and never will’) over his father’s death. This is something echoed in the very title of Alan Cumming’s book Baggage. The triumphant ending of his 2014 memoir Not My Father’s Son, which seemed to exorcise the ghost of his abusive father was, Cumming now implies, a cop-out. ‘I am a survivor,’ he writes, ‘but not cured’: even at the moments of his greatest triumph, he has felt unhappy and confused, and he still thinks about his father almost as much as he ever did.

The book’s message, he says, is ‘Don’t buy into the Hollywood ending’: damage done in childhood will always be there as ‘a residual virus’: one has just to learn to live with it. And yet, as he charts his career from the collapse of his first marriage to contentment and freedom in his second, from his Broadway-conquering emcee in Cabaret to his starry, fully-packed life today, he makes the Hollywood ending sound completely credible. If his first book showed him confronting his bullying father, in Baggage he not only stands his ground against Stanley Kubrick (‘who found me intriguing because of it’) but also co-leads an actors’ mini-rebellion against X2 director Bryan Singer. It may not be happy ever after, but it sounds close enough …

Then again, two anecdotes from Baggage made me wonder just how accurately art can ever mirror life. While staying with Gore Vidal – a boor when drunk, apparently – he hears him confess that he never was really in love with his school classmate Jimmy Trimble, no matter what he wrote in his memoir Palimpsest. And then there’s Cumming’s Liza Minelli story.

He’d watched one of Minelli’s one-woman shows in New York, in which she told a story about how, when she was 16, she’d invited both her mother (Judy Garland) and godmother to see her perform, even though it was only a ten-second dance solo and miles away. The two women turned up, watched the show, and were in tears afterwards. Neither had a hankie, so Garland got out her powder puff and they dabbed their faces with it. Going backstage, they told Liza what they’d done, and then gave her the powder puff, still stained with her own and Liza’s godmother’s tears. ‘And I still have that powder puff to this day,’ Minelli told the crowd, to cheers and applause.

After the end of that show, Cumming asked her whether that story was true.

‘No darling!’ she replied. ‘None of that ever happened!’

‘And that, ladies and gentlemen,’ he concludes, ‘is show business.’

Putting the Rabbit in the Hat: My Autobiography by Brian Cox is published by Quercus, priced £20.

Baggage: Tales from A Packed Life by Alan Cumming is published by Canongate, priced £18.99

As we gear up for Halloween this week, BooksfromScotland took the time to speak to Alice Tarbuck, author of A Spell in the Wild, about her book and about everyday magic.

A Spell in the Wild

By Alice Tarbuck

Published by Two Roads

Your book A Spell in the Wild is having its paperback release this month. How have you enjoyed its reception with readers since its hardback release last year?

Perhaps the most surprising and wonderful thing has been the number of people who have read the book chapter-by-chapter, and followed through the whole year with it. I think that’s genuinely incredible, to think that people have used the book as a monthly comfort – I’ve had so many people reach out to tell me about the ways that following along with it has changed how they interact with nature in the world.

A Spell in the Wild is part-memoir, part-primer, part-history on magic and witchcraft. What precipitated your decision in writing the book?

The book naturally synthesised out of my doctoral research, and my love of academic research more generally, my private practice, and my experiences of the world – it felt natural to combine all three into something that I hoped would change and broaden the conversation around magic, witchcraft and the esoteric – something with robust research that nevertheless didn’t require you to be any sort of ‘expert’ to access the world you already live in!

It’s very interesting that in the introduction to the book that tell the readers you didn’t think to consider yourself a modern witch until someone pointed it out to you. Why do you think that was the case?

I think often we are still encouraged to believe that witchcraft is an exclusive, initiatory practice, which only certain people can participate in, and only after long training. It turns out of course that this isn’t true at all, but I am very aware that many people still see this model in culture. Its one of the reasons that, with Claire Askew, I teach witchcraft courses – to show people that this knowledge is accessible, its okay, its allowed.

Autumn has arrived now. What kind of practices will you be following in this seasonal change?

Some are very small – more soups and stews, fairy lights, but its also gearing up for Samhain, or Hallowe’en, which is considered ‘the witches’ new year’, so I take that seriously in terms of letting things go from my life that I wish to be rid of, and letting things in that I want to invite.

What do you recommend as practices, as engagements with the natural world, for those who are starting out?

I recommend just opening your eyes to the world – picking up fallen leaves, noticing when the moon is full (an app can help with that) and even just taking more nature photos – whatever opens your eyes!

There’s a practicality in your book, a recognition of what’s possible in any and all environments, to root magic in the everyday. Why is that important to you?

As someone with a chronic illness, and who is aware of how climate crisis affects our planet, and as someone who has grown up in a city, I think its easy when starting out to feel really alienated from the witchcraft of pristine landscapes so often put forward in books of the sort – I wanted to re-situate witchcraft, as occurring where we actually are!

Can you tell us anything about your current writing projects? What else can readers look forward to?

I’m currently working on my first poetry collection!

What have been your favourite books to read this year? What are you looking forward to reading next?

I’m currently enjoying reading Neil Gaiman’s Sandman – better late than never, and can’t wait to read Nina Mingya Powell’s Small Bodies of Water.

A Spell in the Wild by Alice Tarbuck is published by Two Roads, priced £9.99.

Graeme Macrae Burnet’s Case Study has been one of the most anticipated novels of the year, and with good reason – we thoroughly recommend you get a copy as soon as possible! We caught up with Graeme to talk about the books that have inspired him and his work.

Case Study

By Graeme Macrae Burnet

Published by Saraband

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?