In the latest installment of the Mirabelle Bevan series, author Sara Sheridan has her super sleuth up in the Highlands for her latest adventure. BooksfromScotland chatted to Sara about the books that mean the most to her.

Highland Fling: A Mirabelle Bevan Mystery

By Sara Sheridan

Published by Constable & Robinson

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

I was definitely the weird kid in my family and the only one who was into books. We didn’t have much to read around the house when I was growing up, at least not initially, but I encouraged my parents to invest in some books for me. I remember visiting the old Bauermeister shop on George IV Bridge and also going to Morningside Library (which was VERY exciting) I find it difficult to remember much from being very young but my father read me Peter Rabbit and I learned the word soporific and I remember being excited – soporific remains one of my favourite words. I still get excited when I find a new word I like the sound of.

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your latest book Highland Fling. What adventure does Mirabelle Bevan find herself in?

Highland Fling is the 8th Mirabelle Bevan mystery. I’ve been writing my way through the 1950s for 9 years now and I’ve got to 1958 at last! I’ve been dying to bring Mirabelle home to Scotland, but I was waiting for the Cold War to get fully underway… and for her relationship with Superintendent Alan McGregor to get to the point where he could introduce her to his family, specifically, his cousin who lives outside Inverness. I love Agatha Christie and I wanted to write a traditional country house mystery and of course, Mirabelle and McGregor have barely arrived when a the body of a glamorous fashion buyer commissioning a range of cashmere for a New York boutique is found in the orangery. Scotland in the 1950s is fascinating – for a start it’s when we stopped voting majority Tory but also, in the Highlands, most landowners were right wing and had been since before WWII when they mostly supported Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement plans. Plus the 1950s was the genesis of modern press so I wanted to have paparazzi, whisky cocktails and courtesy of the American contingent of characters, a dollop of 1950s New York chic. People often talk about landscape when they talk about Highland Noir, but though the scenery is lovely, I think the character of Highlanders, particularly Highland women is unique, so I wanted to explore that – hard as nails, no nonsense and genuinely thrawn.

The book as . . . object. What is your favourite beautiful book?

This is a tough one. I love Kate Leiper’s illustrations and her Illustrated Treasury of Scottish Mythical Creatures is magical. But also, I am obsessed with maps. I’ve got Edinburgh Mapping the City by Chris Fleet and Daniel MacCannall on my desk at the moment and I love it. But then, the Common Weal’s Atlas of Opportunity is also on display in my study and has been since it came out cos I want to keep it in mind.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

Straight up – my daughter wrote me a notebook for my birthday this year of memories and also of things we’ve learned and how we’ve grown in our family since she left home and it’s the most inspiring thing I’ve ever read. So personal but important to me.

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

When I met my now-husband, he gave me a copy of Water Music by TC Boyle which is hands-down my favourite historical novel and I suppose I knew then he was a keeper (the husband, not TC Boyle)

The book as . . . entertainment. What is your favourite rattling good read?

I love Eva Ibbotson – she’s my favourite mid-20th century writer and her novels for adults are good-hearted and whizz along. I’d choose A Countess Below Stairs or Madensky Square. That’s what I’d take to the beach.

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

I go back again and again to Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s Worst Journey in the World which is his account of his expedition with fellow Antarctic explorers Birdie Bowers and Edward Wilson when they walked through the harsh Antarctic mid-winter to collect Emperor Penguin eggs. The book was recommended to me by a writer friend I bumped into deep in the shelves of Thins on South Bridge. It’s probably why I wrote The Ice Maiden which was my imaginative response to the stories about polar explorers of the heroic age – with an added supernatural element.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

Because I’m writing a novel right now and I find it difficult to read fiction and write fiction at the same time, I’m saving books to read. When I next get a reading break, I’m slowly working my way through some of the little-known female Scottish writers I discovered last year while writing Where are the Women? So I have a Jane Porter novel on the side plus Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver and also an anthology of short stories to which I contributed a Mirabelle Bevan short – I’m dying to read the others. It’s called Noir from the Bar and all the profits go to the NHS.

Highland Fling: A Mirabelle Bevan Mystery by Sara Sheridan is published by Constable & Robinson, priced £8.99

There has been a real resurgence in interest in the Scots language, and poet, Stuart Paterson, has a new collection for bairns to get that interest started early. Here are a few poems from his latest collection that’ll fair mak ye greet wi’ lachter!

Poems taken from A Squatter o’ Bairn Rhymes

By Stuart Paterson

Published by Tippermuir Books

The Tobermory Dodo

Whit’s yon ye say?

Ye’ve never heard

O Tobermory’s

Wingless burd?

Ane day it grew

Gey seek o copin,

Upped an skreighed fareweel

Tae Oban.

Flew tae Mull

A while tae bide,

Lost the baith its wings

An steyed.

Alas, it ate

Jist Cullen Skink

An twae year later

Wis extinct.

Ma Wee Mammy

Ma wee mammy

Is the bravest wee mammy.

She disnae greet nor wheenge

When her leg gets gammy,

She jist gets tae wark

Wi a duster or a shammy.

Ma wee mammy

Is the bravest wee mammy.

Ma wee mither

Is the hardiest wee mither.

In a stooshie or a barnie

She’ll no stop nor swither,

She’ll tell ye whit’s whit

An she’ll clap yer heids thegither.

Ma wee mither

Is the hardiest wee mither.

Ma wee maw

Is the smertest wee maw.

She kens jist aboot aathing

But there’s nae wey she’s a blaw,

Her heid’s aye in a beuk

An whit she disnae ken’s hee-haw.

Ma wee maw

Is the smertest wee maw.

Ma wee mammy

Is the smashinest wee mammy.

Ah’m tellin ye Ah’m lucky,

Pure fortuitous an jammy

That ma maw, ma mither, mammy

Is the very cat’s pajammies

An gin ye say ocht different

Then we’re gonnae hae a rammy!

Ma wee mammy

Is the best wee mammy in the warl –

An so is yours!

Space

The universe

Is lang an wide,

It has nae bottom

Tap nor side.

When did it stert?

When will it feenish?

Thinkin o it

Maks me squeamish.

Mixter-Maxter

In Scotland oor wirds

Are gey different, aye.

When ye speir someone how?

Then yer speirin them why?

Piece isnae a fragment

It’s somethin ye eat

Wi twae dods o breid

An cheese or cauld meat.

An when ye feel doon

Then ye micht stert yer greetin –

Elsewhaur it’s somethin

Pals dae when they’re meetin.

When ye bide here in Scotland

In north, sooth or centre

Then mind’s no yer mind

It’s the wird tae remember.

A tap isnae somethin

Ye turn on fir watter

It’s somethin ye weer

In cauld chitterin wather.

A burn willnae burn ye

Burns are aa roon ye

Though dinnae loup in

In case the burn droons ye!

A press willnae press ye

A press ye’ll discover

Is whit thaim in England

Will aye cry a cupboard.

Messages arenae

The texts that ye’ve got,

They’re whit ma an da

Will bring hame fae the shop.

A poke’s no a prod

An whit’s in it’s delish,

Yer braw sausage supper

Or chips wi yer fish.

Ginger elsewhaur is aye

Kennt as a spice.

In Scotland it’s juice

An tastes fower times as nice.

Mince isnae aye

Whit ye hae wi yer tatties –

If ye talk it they’ll cry ye

A richt glaikit daftie!

Ken is a name

Jist like Jimmy nor Joe.

Up here it’s the wird

That some Scots yaise fir know.

A hen is a chookie,

Lays eggs an scrans grass.

In Scotland it’s whit

Ye cry wummin or lass.

An dinnae tell fowk

That ye fair like tae hum –

It means ye’ve no waasht

Or no dichtit yer bum!

A Squatter o’ Bairn Rhymes by Stuart Paterson is published by Tippermuir Books, priced £7.99

Emma Major has been inspiring many with her thoughtful and distinctive illustrations in her book, Little Guy, which offers a gentle path to finding a way through anxiety. She even found herself appearing on Grayson Perry’s Art Club during lockdown! Here, we share some of her illustrations with her own video explanations.

Little Guy

By Emma Major

Published by Wild Goose Publications

Little Guy Picture 4

Floating peacefully

Leaving stress and strain behind

Catching calmness

Little Guy Picture 6

Swinging thoughtfully

Breathing deeply; thinking likewise

Looking for uplift

Little Guy Picture 11

Singing joyfully

Not a care in the world

A lesson for me

Little Guy Picture 14

Waves gently lapping

Warm breezes cooling heat haze

Perfect peacefulness

Little Guy by Emma Major is published by Wild Goose Publications, priced £3.90.

If you’re looking for something a little bit different from your crime fiction, then BooksfromScotland recommends you give Claire Macleary’s dynamic duo, Maggie and Wilma, your full attention. There are now four mysteries to catch up on if you’re still to introduce yourselves – Cross Purpose, Burnout, Runaway, and now Payback – and Claire gives us a wonderful reading here. She also takes the time to answer some probing questions . . .

Payback

By Claire Macleary

Published by Saraband Books

Payback by Claire Macleary is published by Saraband Books, priced £8.99

Anthony McGowan’s Lark has won the Carnegie Medal, the UK’s oldest and most prestigious award for children’s literature, published by dyslexia-friendly independent Barrington Stoke, based in Edinburgh.

Author, Anthony McGowan has said of his win:

‘Every writer for young people dreams of winning the Carnegie Medal. Its incredible history, the roll call of the great writers who have won it and the rigour of the selection process makes this the greatest book prize in the world. It is also a magnificent way of connecting with readers. The hundreds of shadowing groups in schools and libraries around the country provide that one thing that writers cannot do without: a living, arguing, debating, biscuit-munching population of brilliant readers!

On one level, Lark is a simple adventure story. Two woefully ill-equipped teenage boys and their old Jack Russell terrier go for a walk on the North Yorkshire Moors. A blizzard descends and their fun day out, their ‘lark’, turns into a desperate battle for survival. On another level, the book is about the unshakeable love between two brothers, one of them with special needs, after enduring family break-up, poverty, bullying and cruelty. Lark is also a story about the power of stories and the way they weave through our lives. The book ends with the words “Tell me a story”, and with those words we are led back again to the beginning.’

BooksfromScotland are so thrilled to hear Barrington Stoke’s great news, that we thought we’d share the first chapter of this amazing, and now award-winning, story. Treat yourself to this taster – we’re sure it will make you want to read the rest!

Lark by Anthony McGowan is published by Barrington Stoke, priced £7.99

If you’ve yet to make your acquaintance with Douglas Watt’s fictional investigator, Advocate John Mackenzie, has he solves criminal cases against the backdrop of 17th century Edinburgh, then BooksfromScotland urges you to rectify that immediately! This month, Luath Press brings out a brand new adventure, where Mackenzie’s life has changed since the political upheavals following the revolution in 1688. When he is tasked by an enemy to investigate a merchant’s brutal murder, he is, at first. reluctant, fearing ulterior motives. But he is soon is drawn in to the mystery, and in this extract, we follow him as he observes the scene of crime.

Extract taken from A Killing in Van Diemens Land

By Douglas Watt

Published by Luath Press

He returned to the kitchen and examined the range. Had something been burned there in the night? He took a rag and opened the small metal door, peering inside. It had burned out and was full of ash. A small white shape caught his eye at the front. He picked it up delicately. It was a small fragment of material, a couple of inches in length, partly burned. He placed it in his pocket and stood for a few moments more, contemplating the scene, recalling the kitchen of his foster mother years before when he was a boy in the Highlands. It had been his job to make sure the range was supplied with a plentiful supply of peat. He had taken a particular pleasure in the responsibility, carrying the basket back and forward from the peat stack. He remembered the sweet odour of burning peat filling the house. The range in Van Diemen’s Land used coal. A scuttle sat beside it. He picked up a lump of coal and stared at it, before dropping it back into the scuttle.

On the way out the kitchen, MacKenzie cleaned his shoes with the rag to remove any blood picked up from the floor. He climbed the stairs to the ground floor and walked down the narrow hall to check the front door. It was bolted securely and the lock appeared sound. He turned into Kerr’s trading premises on the right, a large bright room full of bales of cloth which included calico, blue linen, brown linen, diaper, serge and Yorkshire. A fine bale of green linen and some high-quality muslin caught his eye. Kerr must have had rich customers.

The window at the front of the chamber which looked out on the courtyard was made up of dozens of tiny rhomboid panes of glass. They were all intact. Another window at the back of the chamber looked out onto the rig behind and there was a door to the garden. The window was also barred with iron and intact. MacKenzie entered the office on the left. It had one tiny window, high on the wall which was too small for anyone to enter through. Inside the office, documents and papers were strewn over the floor and the desk had been ransacked.

There were two kists on the floor. The lid of the smaller one was open. MacKenzie got down on his haunches. A key, part of a set, was in the lock and the kist was empty. He turned to the larger kist and found it was locked. He tried to move it along the floor, but it would not budge more than a few inches because it was chained to the wall. He took the set of keys from the lock of the small kist. The second one fitted and he opened the larger one. Inside was a pile of bonds, notes and bills of exchange. Underneath the stack of paper, he found a pistol, as well as gold and silver coins, guineas and pieces of eight. He quickly estimated they came to a healthy sum – a couple of hundred pounds sterling at least. The burglar had chosen the wrong kist.

MacKenzie returned to the back door and noticed it was very slightly ajar. He pulled it open carefully. It provided access to a stone platform above the basement which led to the yard at the back. It was immediately obvious the lock had been broken. A vision flashed through his mind of the killer entering here, but why did he or she descend into the kitchen? If Kerr had disturbed a thief, he would have confronted the person up here. Or had the thief taken Kerr down to the kitchen for some reason? He closed the door gently and returned to the office to examine the debris on the floor more carefully. Letters and lists lay everywhere. He picked up a random paper – an inventory of cloth Kerr had bought in Amsterdam.

He noticed a line of ledgers on a shelf above the desk. He looked through the first fat leather-bound volume. The ledger itemised Kerr’s purchases and sales back in the 1670s. MacKenzie returned it and took the next on the right. The book was only half used. He found a number of transactions dated the day before – three in total. He wrote the names in his notebook. William Spence, Ninian Reid and Archibald Purves were all tailors in Edinburgh. A portrait of Kerr and his wife on the wall opposite the window caught his attention. The painting gave the impression of confidence and wealth, but there was something about the demeanour of Margaret Kerr. MacKenzie noticed again that she was a fine-looking woman, if a serious one. From the picture she hardly appeared a happy wife. A knock on the door startled him. Margaret Kerr herself stood at the doorway; the same beautiful, unhappy face in the painting, although a little older.

She spoke first. ‘Was the motive theft, Mr MacKenzie? I see the back door has been broken.’

‘It’s too early to say, madam’, replied MacKenzie.

She moved into the room and looked at the kists. ‘My husband always carried the keys with him. Everything is gone from the smaller one.’

‘It may be burglary’, replied MacKenzie, nodding. ‘But I haven’t seen around the house yet. Where did your husband keep his keys?’

‘They were always on his belt. He wore his belt even in bed at night. He never took it off.’ She crossed her arms over her chest and looked away.

MacKenzie moved closer to her. ‘Do you know what’s been taken from here?’

‘The cash was kept in the larger one. The small one contained items concerned with daily business. Maybe some bonds… correspondence, that kind of thing, a little petty cash perhaps. He kept important things in the larger one.’

‘Why would a thief take the papers from the small kist and not try to open the larger one?’ asked MacKenzie. She did not reply and shook her head. MacKenzie turned back to the portrait, smiling. ‘A fine likeness. When was it painted, madam?’

She stood transfixed for a few moments staring at the image, before coming back to herself. ‘About ten years ago. A Dutch artist was in town painting nobles and lawyers and merchants. It cost us a pretty packet. Jacob was adamant we should be recorded for posterity. The artist was impressed by the Dutch name of our house. He was disappointed to learn we did not belong to the original family.’

MacKenzie smiled. ‘Is it a good likeness of your husband?’

She looked at the painting again, and as she did so, dropped to her knees. She cried out, ‘What are we to do now, sir? Why has God forsaken us? Why has He taken him?’

MacKenzie helped her back to her feet. As she looked up at him, he saw for an instant the younger woman in the portrait. She was bonnie indeed, if a tad severe, like many Scottish lasses. The ministers and elders of the Kirk, like her husband, demanded their wives dress like crows. He looked again at the portrait. Kerr appeared confident to the point of arrogant with a large belly protruding over his belt. And there were the keys hanging from it. The keys he slept with. The security of his house and the kists was paramount to him as a merchant. MacKenzie observed Kerr’s large florid cheeks, cold eyes and double chin. Something made MacKenzie shudder at the owner of Van Diemen’s Land.

He turned from the painting and nodded at Mrs Kerr. ‘I’ll take in the rest of the house myself, madam.’

A Killing in Van Diemens Land by Douglas Watt is published by Luath Press, priced £8.99

Renowned naturalist Gavin Maxwell may be better known for his time spent on the west coast of Scotland, but he is a son of Galloway, and learned his love of nature there. His most famous book, A Ring of Bright Water, is considered one of the pioneering texts in nature writing, and we are delighted to share an extract. Here, he shares the fledgling daily routine with his otter, Mij, who has travelled with him home, via London, from the Middle East.

Extract taken from A Ring of Bright Water

By Gavin Maxwell

Published by Little Toller Books

We arrived at Camusfeàrna in early June, soon after the beginning of a long spell of Mediterranean weather. My diary tells me that summerbegins on 22nd June, and under the heading for 24th June there is a somewhat furtive aside to the effect that it is Midsummer’s Day, as though to ward off the logical deduction that summer lasts only for four days in every year. But that summer at Camusfeàrna seemed to go on and on through timeless hours of sunshine and stillness and the dapple of changing cloud shadow upon the shoulders of the hills.

When I think of early summer at Camusfeàrna a single enduring image comes forward through the multitude that jostle in kaleidoscopic patterns before my mind’s eye – that of wild roses against a clear blue sea, so that when I remember that summer alone with my curious namesake who had travelled so far, those roses have become for me the symbol of a whole complex of peace. They are not the pale, anaemic flowers of the south, but a deep, intense pink that is almost a red; it is the only flower of that colour, and it is the only flower that one sees habitually against the direct background of the ocean, free from the green stain of summer. The yellow flag irises flowering in dense ranks about the burn and the foreshore, the wild orchids bright among the heather and mountain grasses, all these lack the essential contrast, for the eye may move from them to the sea beyond them only through the intermediary, as it were, of the varying greens among which they grow.

It is in June and October that the colours at Camusfeàrna run riot, but in June one must face seaward to escape the effect of wearing green-tinted spectacles. There at low tide the rich ochres, madders and oranges of the orderly strata of seaweed species are set against glaring, vibrant whites of barnacle-covered rock and shell sand, with always beyond them the elusive, changing blues and purples of the moving water, and somewhere in the foreground the wild roses of the north.

Into this bright, watery landscape Mij moved and took possession with a delight that communicated itself as clearly as any articulate speech could have done; his alien but essentially appropriate entity occupied and dominated every corner of it, so that he became for me the central figure among the host of wild creatures with which I was surrounded. The waterfall, the burn, the white beaches and the islands; his form became the familiar foreground to them all – or perhaps foreground is not the right word, for at Camusfeàrna he seemed so absolute a part ofhis surroundings that I wondered how they could ever have seemed to me complete before his arrival.

At the beginning, while I was still imbued with the caution and forethought that had so far gone to his tending, Mij’s daily life followed something of a routine; this became, as the weeks went on, relaxed into a total freedom at the centre point of which Camusfeàrna house remained Mij’s holt, the den to which he returned at night, and in the daytime when he was tired. But this emancipation, like most natural changes, took place so gradually and unobtrusively that it was difficult for me to say at what point the routine had stopped.

Mij slept in my bed (by now, as I have said, he had abandoned the teddy-bear attitude and lay on his back under the bedclothes with his whiskers tickling my ankles and his body at the crook of my knees) and would wake with bizarre punctuality at exactly twenty past eight in the morning. I have sought any possible explanation for this, and some ‘feed-back’ situation in which it was actually I who made the first unconscious movement, giving him his cue, cannot be altogether discounted; but whatever the reason, his waking time, then and until the end of his life, summer or winter, remained precisely twenty past eight. Having woken, he would come up to the pillow and nuzzle my face and neck with small attenuated squeaks of pleasure and affection. If I did not rouse myself very soon he would set about getting me out of bed. This he did with the business-like, slightly impatient efficiency of a nurse dealing with a difficult child. He played the game by certain defined and self-imposed rules; he would not, for example, use his teeth even to pinch, and inside these limitations it was hard to imagine how a human brain could, in the same body, have exceeded his ingenuity. He began by going under the bedclothes and moving rapidly up and down the bed with a high-hunching, caterpillar-like motion that gradually untucked the bedclothes from beneath the sides of the mattress; this achieved he would redouble his efforts at the foot of the bed, where the sheets and blankets had a firmer hold. When everything had been loosened up to his satisfaction he would flow off the bed on to the floor – except when running on dry land the only appropriate word for an otter’s movement is flowing; they pour themselves, as it were, in the direction of their objective – take the bedclothes between his teeth, and, with a series of violent tugs, begin to yank them down beside him. Eventually, for I do not wear pyjamas, I would be left quite naked on the undersheet, clutching the pillows rebelliously. But they, too, had to go; and it was here that he demonstrated the extraordinary strength concealed in his small body. He would work his way under them and execute a series of mighty hunches of his arched back, each of them lifting my head and whole shoulders clear of the bed, and at some point in the procedure he invariably contrived to dislodge the pillows while I was still in midair, much as a certain type of practical joker will remove a chair upon which someone is in the act of sitting down. Left thus comfortless and bereft both of covering and of dignity, there was little option but to dress, while Mij looked on with an all-that-shouldn’t-really-have-been-necessary-you-know sort of expression. Otters usually get their own way in the end; they are not dogs, and they co-exist with humans rather than being owned by them.

A Ring of Bright Water by Gavin Maxwell is published by Little Toller Books, priced £14.00

Scotland is lucky to have brilliant publishers based all around the country. In the South-West, we have Curly Tale Books who publish gorgeously-illustrated books for children. We asked publisher, Shalla Gray, to tell us more about Curly Tale’s publishing journey.

Curly Tale Books is an independent publisher based in Galloway, South-West Scotland. Our aim is to produce beautiful books for children rooted firmly in the countryside of this beautiful part of the world. Co-founded in 2013 by author and illustrator Shalla Gray and author Jayne Baldwin (who has since left the business to pursue her dream of running a children’s book shop in Wigtown, Scotland’s Book Town), Curly Tale Books has published 13 books thus far, with a 14th just gone to print. More about that later…

Curly Tale Books is proud to have been awarded the Galloway & Southern Ayrshire Biosphere Chartermark, which signifies our commitment to follow sustainable business practices to help protect and conserve the resources and environment of our amazing region. After all, without our fabulous rural landscapes there would be no stories to tell! Our ethos is to support our local economy and the environment as much as possible, for example all our books are now printed on 100% recycled paper, and we get all our books printed in the UK.

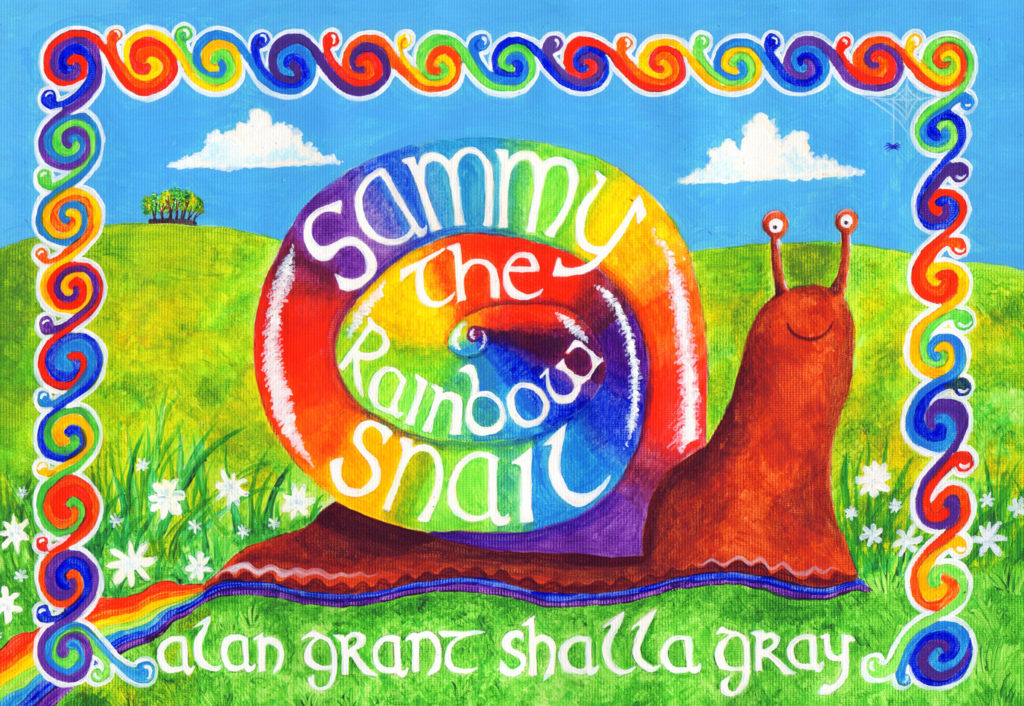

Our first published book was The Quite Big Rock by comics legend Alan Grant. As well as writing Batman, Judge Dredd and many other superhero titles, he is also Shalla’s Dad, and many years ago, before he got into comics, he wrote stories to tell her at bedtime. We have two of these stories on our list, the other being the psychedelic Sammy the Rainbow Snail.

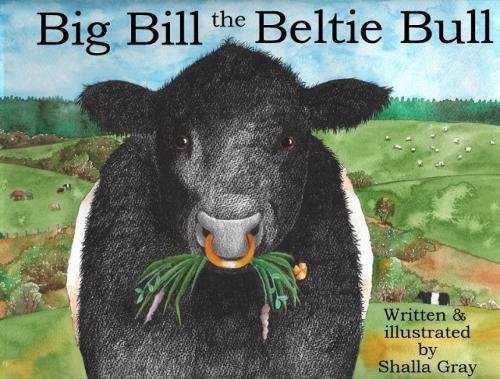

Our bestselling book is Big Bill the Beltie Bull, written and illustrated by Shalla. Belties are a cattle breed originating in Galloway with a distinctive white belt around their tummies. Big Bill goes (against his will) to the local show and surprises himself by winning first prize! We have received so many photos of children dressing up as Big Bill for World Book Day, he really captures their imagination! Jayne wrote two sequels to this top-seller, Big Bill’s Beltie Bairns and Big Bill and the Larking Lambs, which continue to sell really well.

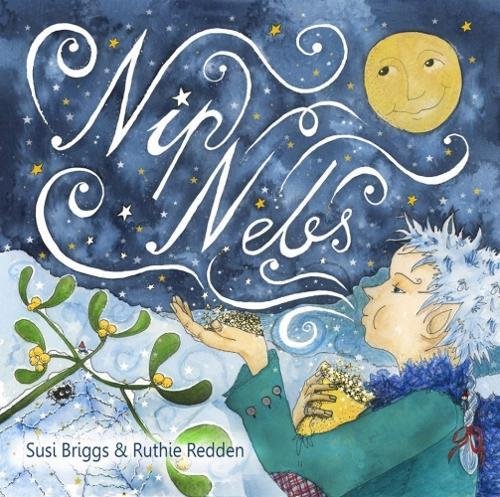

A chance meeting at an art exhibition led to Curly Tale Books publishing Nip Nebs – Jack Frost in Scots by Susi Briggs and Ruthie Redden. Shortlisted for the Scots Bairns Book of the Year in 2019, Nip Nebs is one of the few original titles written in Lowland Scots for children. Author Susi is extremely passionate about the Scots language, and in 2019 we were delighted to be awarded a Scottish Book Trust Grant for the publication of a sequel to Nip Nebs, entitled The Last Berry.

Alasdair Hutton, the voice of the Edinburgh Tattoo and a great admirer of Sir Walter Scott was our next signing, having penned a children’s story featuring Scott’s Dandie Dinmont Terriers, now a rare breed. Who would have thought that there were so many Dandie Dinmont fans! The book raced off the shelves and we are currently in talks about a sequel.

All of these books are set firmly in Scotland – the landscapes and characters are Scottish, and we have carried this theme on with our next book, Strange Visitor. This is a retelling of a traditional Scots tale by Renita Boyle, illustrated in a dark, graphic novel format by Mike Abel, and is so unusual that it almost defies description!

All of the authors, and many of the illustrators on our list do fantastic events for children. Susi Briggs for example has workshops based around Nip Nebs which also educate the participants about the Scots language in a very engaging way. Renita Boyle was a storyteller before she became an author, and she has an amazing knack with children – she can keep a whole school enthralled with her singing and stories! Shalla loves doing events at schools and nurseries, who often do farming-related topics which fit in nicely with her stories, and she has a large variety of activities and games to go along with each book.

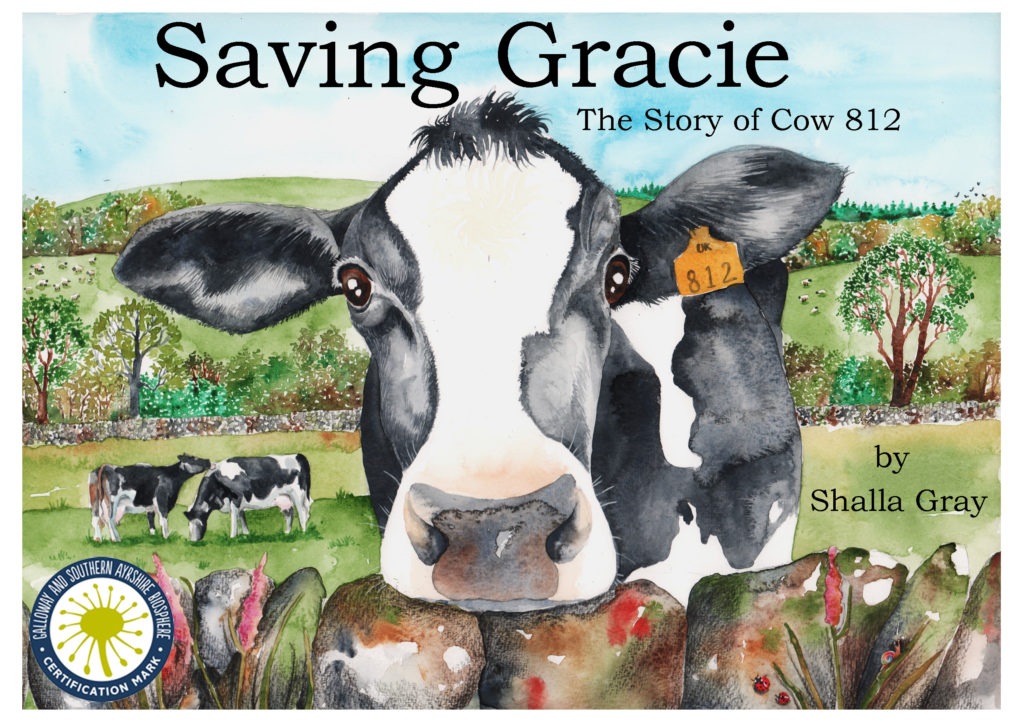

So, what next on the Curly Tale Books journey? Well, we are really excited to announce our next book Saving Gracie: the Story of Cow 812. Written, illustrated and printed in record time during lockdown, it is the result of a collaboration with Youtube sensation The Hoof GP, a local hoof care specialist whose little boys love our books. He has a cow called Gracie in his care who has attracted hundreds of thousands of followers, and he approached Shalla to ask if she would be interested in telling Gracie’s story. She was immediately inspired, and the resulting book is due out later this month…

To find out more about Curly Tale Books, visit their website.

Stephen Rutt moved to the Solway Firth in 2018, and wrote about the geese there in his book Wintering: A Season with Geese. Before he moved to the South-West of Scotland, he travelled the country charting sea birds and wrote of the experience in his Saltire-winning book, The Seafarers: A Journey Among Birds. To celebrate the release of the paperback of The Seafarers, we share an extract here for you to enjoy.

Extract taken from The Seafarers: A Journey Among Birds

By Stephen Rutt

Published by Elliot & Thompson

Birds were my awakening to the world outside. Birding teaches you to be aware of subtle distinctions that signify differences. Whether it was the leg colour or a few millimetres’ difference in wing length that enabled me to tell two common warblers apart, or the presence of a wing-bar that revealed it to be extremely rare. Whether I was standing in an overgrazed field, a set-aside field or a meadow rich in life that an owl would soon fly over through the thick light of dusk. Whether the wind in October was coming from the north and my day out would be cold and boring, or whether it was coming from the east and it would be cold and rich in potential. It made me pay attention, not just to these things, but to how and when they change. Whether my first swallow of the year was in March or May – and why. Birding forces you to pay attention to the world as it happens around you and gives you a way of decoding it.

Before I became a birder, I was briefly a fisherman. While sitting behind a rod, fruitlessly waiting, I never thought about global warming, the rise in sea levels, or how the algae in the bay of the lake might be caused by the run-off of unpronounceable agrochemicals with startling side effects. Fishing taught me futility – that things will probably not go your way. Birding taught me to look at and think about the outside world, to engage with the landscape and all it holds.

There is a gentle art to birding. By which I mean there is no correct way to do it. You can go outside for days or just glance out of a window, notice something, and carry on, your day having become slightly wilder, slightly more interesting than it might otherwise have been. It requires no basic equipment other than your own senses and a desire to notice and to know. Birding makes no demands of you other than these. It is gentle because you can’t force it. It is more productive not to, better to slow down to the speed of the landscape and blend with it. It is an art because there is no set route, no magic key to finding or knowing a bird. To recognise one requires a myriad of moment-specific considerations. And much of it can be done by intuition – the application of experience – rather than rules. You never stop learning. It can open you up to things either extraordinarily beautiful or extraordinarily depressing.

Being a teenager enabled me to be obsessed without shame. I absorbed the Collins field guide to the birds of Europe. Then Sibley’s field guide to American birds. Then the monographs to specific families of birds, then specific species. I absorbed site guides, built a mental map of the world’s birds, read blogs, dissected forums. I found a network of others from across Europe and we spent evenings indoors, online, talking about mornings outdoors. We were captivated by the Scottish islands. I had never been but, from the photos I had seen and the books I had read, I constructed my own mythic version of them: quiet, solitary utopias, places where one could not ignore nature, and if one tried then nature would come and find you. Come and rattle at the windowpanes, or land in your garden, or squat on your car bonnet, until you were forced to pay attention again. A place for the inveterately shy.

*

To understand the appeal of a seabird, it’s necessary to explore what a seabird is, and what it isn’t. Most birds migrate, most will cross a sea. They are not seabirds, not any more than a seabird becomes a landbird when it sets up residence on a cliff to breed every summer.

A scientist’s definition might focus on how they have feathers covering their auditory canal, to prevent water entering their ears when they dive for food, or to prevent flying with muffled hearing, or – more likely – to minimise the effects of pressure. Another scientist’s definition might focus on the Procellariiformes: the order that contains the petrel, shearwater and albatross families. They have a tubenose: a prominent bulging nostril above the bill, an adaptation specific to these families, allowing them to smell food on a sea breeze and expel the salt from their exposure to saltwater. But this would be partial definition. It would not include the auks, gannets, gulls, skuas, terns and eiders – all of which are predominantly found, or should be found, on the edge. Some might focus on their power of smell, unusually highly developed in some seabirds, while most other birds cannot smell particularly well. The problem is that all definitions of a seabird are partial. Most would exclude the eider. They might live on the coast, but they feed at sea. It is the sea that defines them and their capacity for coping with it makes them difficult, makes them wild, makes them captivating. The ‘should be found’ is important here – though some birds always end up lost, things are changing on this front. Some are moving inland.

Seabirds live predominantly out to sea – feed at sea, sleep at sea, and experience a habitat that is simultaneously as vast as the ocean and as small as the gap between two waves. Seabirds are mysterious. Away from islands, they are usually seen from land only when summer storms push across the Atlantic and sweep them towards the ocean’s edges. Seabirds love islands, as I love islands: the further out of the way they are, the less disturbance there is, the more perfect they are. All use them to breed – an act of convenience – though the vast majority occupy tiny cliff ledges, several hundred metres above the sea. It’s technically land, but I wouldn’t want to stand there.

Seabirds are transient, fleeting, remote things – yet they are also moving into towns and cities. When they are written about, they reveal a good deal about the author. As with all animals, they are good subjects on which to project human desire. Seabirds are some of our most loved and hated species. They inspire religious devotion or revolutionary zeal. Hermitic living or the hectic crowd. They are symbols of revolution, pirates and victims. They are bounteous and declining – and, like almost everything symbolic of the remote and wild, they are deeply touched by human activity: pollution, over-fishing, the warming of the seas.

Stephen Rutt has been commissioned to write a short book, The Saltmarsh Library by the Wigtown Festival as part of Scottish Natural Heritage’s Year of Coasts and Waters. It will be published in the Spring of 2021 and forms the focal point of Wigtown’s ongoing activity outwith the festival. You can find out more on the Wigtown website.

The Seafarers: A Journey Among Birds by Stephen Rutt is published by Elliot & Thompson, priced £9.99

Patrick Laurie’s memoir on a year in the life of his Galloway farm invites David Robinson to think about the changing nature of our countryside.

Native: Life in a Vanishing Landscape

By Patrick Laurie

Published by Birlinn Ltd

Patrick Laurie is always falling in love. The first time, the object of his affection is ‘blotchy, soft and perfectly gorgeous’. The second time, it’s her shape that attracts him – ‘a broad, tubby barrel with a wrinkle of fat around her neck’. Years later, he has a brief encounter that puts them both in the shade. ‘I smiled at the thickness which seemed to be unfolding in her legs and over her back. Deep veils of hair wobbled across her breast …’

We are, I should add, talking about ‘Riggit’ Galloways, and if you don’t know what they are, you almost certainly have never been smitten in a crowded auction mart by the urge to possess a local cow with a white stripe (‘riggit’) down its spine. Laurie, however, has, and in Native: Life in a Vanishing Landscape, he outlines why the breed has such a strong appeal to him.

Apart from their sheer bovine beauty, one reason is that ‘Riggits’, too, are natives. Go back to, say, 1800 and Riggit Galloways would already have been a century on the land Laurie farms near Dalbeattie, where his farmhouse is a century older still. Such continuity is precisely what’s vanishing from the landscape: older, smaller, cattle breeds are gradually being replaced by bigger, faster-fattening modern ones. In the process, not only did we lose better-tasting meat but a whole heap of biodiversity too.

In an interview accompanying its launch*, Laurie says he sometimes finds it difficult to explain what his book is about, and you can see why. There’s no immediately obvious focus. You might think it’s going to be about Galloway itself, but there’s precious little Gallovidian history in it, nor is it any kind of guide to what to see when you go there for a post-lockdown tour. There’s not too much about Laurie himself either or indeed anything about the upland farm conservation projects he has worked on that are mentioned on the inside back flap. Instead, Native starts out as lyrical trot through the farming calendar of the kind that you might well have read before. Stick with it, though, and it shakes loose from the format and becomes altogether more engaging.

At first, Laurie thought about calling it ‘the curlew book’. He had already written one about the black grouse, and curlews are far more important to him: they were the sound of his childhood, the music of his hills, and he has become obsessed with their survival. For curlews too are natives, even though ‘at the rate they’re going now they’ll be gone in a decade.’

But this isn’t a curlew book no more than it is about fancying gorgeous Riggit Galloway calves. Both feature heavily, both are becoming marginalised, both show the kind of countryside we are losing, and both can be used as a kind of shorthand for how it could be transformed. It’s this natural nexus that lies at the heart of the book and no, I don’t know how you’d work that into a punchier title either.

Curlews still come to Galloway, Laurie points out, but increasingly they’re just flying past on their way to lay their eggs in Finland or Russia. They’re hardly nesting here anymore, or at least not successfully: of the 111 attempts he’s watched in the last eight years, only 12 pairs survived long enough to produce chicks and only one chick lived long enough to fly.

For this, he blames three key F-factors: foxes, forests, and foot and mouth. Vast numbers of Galloways were slaughtered in the BSE crisis of the Nineties and faster-growing modern breeds were chosen to make up the numbers. Unlike Galloways, though, the new breeds won’t eat moorland grass or generally clear the way for the kind of habitat curlews seek out. Instead hybridised ryegrass continues its spread: a superfood with high nitrogen content, but one which could spell an end to the kind of plant and insect diversity curlews need.

This, in essence, is what Laurie is trying to reverse. It might sound like a fanciful ambition, and there are times, like when he opts to make hay rather than silage, when local farmers probably wonder what he’s playing at. Why does he harvest (and thresh) his field of oats by hand? Why does he forego an extra cutting of the grass that could provide him with two or three times more feed? The answer – an earlier cutting would devastate wildlife – would be lost on the students he meets at a local agriculture college. His fellow pupils, he says, ‘had never heard of curlews’.

The life he has chosen is a hard one, and he doesn’t shy away from making it harder still, constantly learning new skills such as how to mend his ancient David Brown tractor, sow a field of oats or slaughter a pig. But some of those hardships pay off: his bacon makes the shop-bought stuff ‘taste like wet salty paper by comparison’; the wild flowers return to the meadows; his herd of Riggit Galloways – he makes their meat sound so appetising that I’m determined to seek it out – slowly builds and he sells his first one. The old ways might be tiring and leave your hands calloused and scarred, but maybe they are the best after all.

The steady growth of his herd is a sad contrast to the childlessness he and his wife endure despite treatments for infertility. In the book’s penultimate chapter, Laurie describes the emotional toll this has taken on him. Sometimes, he says, working with his Galloways has fuelled his stoicism – they don’t question, the hills don’t question, so why should he? – yet at other times he feels ambushed by feelings of despair. He just doesn’t know, he says at the end of the book, whether he ever will have a child.

Well, I do. And he has. A little boy. And it’s a tribute to how much I enjoyed Native that I can’t tell you how glad I was to find that out.

* If you want to catch up with Patrick’s launch event, you can view it here.

If you would like to read an extract from Native: Life in a Vanishing Landscape, you can do so here.

Native: Life in a Vanishing Landscape by Patrick Laurie is published by Birlinn, price £14.99

Jessica Fox swapped her fast-paced life in Los Angeles for a quieter life as a bookseller in Wigtown. She has written a memoir based around her life-changing decision, and BooksfromScotland caught up with her to find out what can happen when you follow a dream.

Three Things You Should Know About Rockets

By Jessica Fox

Published by Short Books

Firstly, how are you doing? How have you been adapting to our current circumstances?

Oh goodness, begin with the hard question first! How are you doing? I mean, is anyone doing ok right now? Instead of making films currently, i’m making online videos. Instead of having a wedding, we got our deposits back and may travel around the US when we can. Instead of seeing my family (god I miss them), we’re collaborating on a podcast. My friend shared a wonderful saying about this strange, scary, full of change Covid time: “we’re all in the same storm, just different boats.” Overall, i’m infinitely hopeful about human innovation and science to rise to this challenge…and I hope our collective capacity for solidarity and compassion makes the journey in each of our boats less of an individual struggle.

You grew up in Boston, then moved to Los Angeles for work, both iconic, busy cities. How did you end up in a fairly remote, small Scottish town?

While working in Los Angeles, I had a vision that kept on appearing: a girl, working behind a long wooden counter in a bookshop somewhere in Scotland. She snuggled into her thick wool jumper as it rained outside, and I could even see the shop had a small golden bell hanging above the door. I thought that this was a screenplay I was destined to write, but the more I explored the vision I soon realised that the young girl was not a character but me. I kept on seeing myself behind that counter in the bookshop. So late one night I typed in “used bookshop” + “Scotland” into google, and Wigtown, Scotland’s National Book Town appeared. There were so many bookshops to choose from so I went for the largest, “The Bookshop”, determined that they might let me do a live/work holiday. After a couple of emails with the owner of The Bookshop, I was on a plane, traveling half way across the world to follow my vision.

It’s amazing that your subconscious led you to Wigtown before you knew it existed. Why do you think the image of a small-town bookshop beside the sea worm its way into your head?

Perhaps the heat of Los Angeles made me crave a place just the opposite: cold, full of ancient buildings, away from traffic and screens, and full of books. Perhaps, as an impressionable filmmaker, I had watched too many romantic comedies. Or perhaps, visions come to you for a deep mythic reason and if you’re brave enough to listen, they will connect you to people, a place and a journey that’s gives you meaning and a sense of being truly alive.

What was your first impression of Wigtown and the bookshop? Did it live up to your dream?

Yes. The Bookshop was exactly like it had been in my dream. At least the front room was – but everything else, the house above, Shaun, our friends, Wigtown, the community – were beyond my expectations. The best thing about dreaming is that it’s just the white rabbit leading you down the rabbit hole. Everything else is the journey – everything you didn’t anticipate – that’s the true gift.

Was it easy to adapt to the cultural differences?

Ha, no. I love Scotland and all things Scottish, but I wouldn’t pretend that I’ve completely adapted…even 14 years on. Wigtown has been incredibly generous towards and accepting of my Americanness.

In LA, you worked for NASA, while trying to build your film portfolio, so your pace of life obviously changed with your move to Wigtown. What did the journey teach you about your relationship with ambition?

Perhaps you have to let go of something to decide whether it’s a vital part of who you are. For me, ambition means believing in your own talents and finding or creating opportunities to express them. The adventure actually bright me closer to my inner ambition. It is an essential part of what makes me feel alive.

When did you know you would write a book about your experiences?

It took a lot of coaxing by a wonderful editor then at Short Books, Vanessa Beaumont. I only realised I could write a book when she encouraged me to, and gave me insightful and supportive feedback.

And you’re still here! What has kept you in Scotland?

My parents would like to know that too! After I got divorced there was a moment where I moved back to Los Angeles. But something in me kept on being called to Wigtown and Scotland. So I returned, co-created The Open Book and still felt connected and at home here. What keeps me in Scotland now is my partner Ash and my work.

If you wanted to encourage someone to visit the South West, how would you recommend the area?

To get there is a bit like finding Neverland, second star to the right and straight on till morning. It is not on the way to anywhere but that’s what makes it such a special place to be. The sense of community is so strong, and so kind. There is so much to explore from ancient history to the arts to nature. Galloway is like mini-Scotland rolled into one: farmland, hills, sea, ancient forests, ruins and ancient sites, towns, lowlands, snow capped highlands – all on your doorstep – and breathtakingly gorgeous.

What are your favourite Scottish books?

James Hogg’s Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, Stevenson’s Treasure Island, anything by Nan Shepard and Shaun Bythell’s Diary of a Bookseller because it captures a very special time in Wigtown.

You still have a great interest in space. What are your thoughts on the current expedition to the International Space Station?

Recent NASA missions are some of the most admirable and successful examples of international team work and partnership. I wish more human endeavors were done as collaboratively across oceans and boarders. This current expedition is exciting because both the private sector and public sector have their own strengths and in tandem in terms of R&D, efficiency, research, they tend to compliment each other well. The future of space exploration will take both public and private partnership. It’s great to see that it works.

What’s next for you?

Lots of possibilities. Currently, I directed a film headed to festivals, my next book is almost done and i’m co-developing a couple of tv shows. So, rather than the sky, imaginations the limit.

Three Things You Should Know About Rockets by Jessica Fox is published by Short Books, priced £8.99.

The wonderful David Macphail has set his latest Thorfinn adventure, Thorfinn the Nicest Viking and the Putrid Potion, in the Great Kingdom of Galloway. If you’ve yet to aquaint yourself with the world’s nicest viking, then we have David reading from a previous Thorfinn adventure for you to enjoy.

Thorfinn the Nicest Viking and the Putrid Potion

By David Macphail

Published by Floris Books

And if you’d like to create your own putrid potion, head over to the Floris website to find our how.

Thorfinn the Nicest Viking and the Putrid Potion by David Macphail is published by Floris Books, priced £5.99

Did you know that the inspiration behind J M Barrie’s classic, Peter Pan, was inspired in a beautiful garden in Dumfries? And that Dumfries have opened the amazing Moat Brae House and Discovery Gardens to pay tribute to this place of literary history? Here we share the story of how the house, which fell into disrepair in the 20th century, has now been restored to become as inspirational to children now as it was to J M Barrie in his childhood.

Patron of the Moat Brae House, Joanna Lumley, talks to us on Moat Brae’s inspiration on J M Barrie writing Peter Pan:

While Moat Brae house was being renovated, they set out their plans for the finished building:

Moat Brae House opened to the public in Spring 2019, and is a beautiful, inspiring place to feed childrens’ imagination. When lockdown is over, we highly recommend you take a trip to Dumfries to discover the wonder of the gardens yourselves.

For more information on Moat Brae House, visit their website.

Scotland’s most famous poet belongs to the South-West, born and raised in Ayrshire, and seeing his last days in Dumfries, so we couldn’t shine a spotlight on the area without paying tribute to Robert Burns. Another writer from Ayrshire, Andrew O’ Hagan, has edited a brilliant, personal selection of his poetry, a perfect taster of the great poet’s works.

A Night Out With Burns

Edited by Andrew O’ Hagan

Published by Canongate

In the best work of the world’s most representative poet, every word can sound like an effusion of pure spirit. And who could mistake Burns’s genius when they encounter his beautiful lyric ‘Green Grow the Rashes’? He once introduced it by saying the song was written in ‘the genuine language of my heart’. A hymn to spontaneous affection over worldly desires, there is nothing else like it. I once knew a retired Ayrshire sailor, Mr Savage. I remember him singing this song one morning as he made his way along the seafront in the town of Saltcoats. The Firth of Clyde appeared to calm itself at the sound of the old man’s voice, as he sang this lilting memorial to a great and simple sentiment.

Green Grow the Rashes

chorus

Green grow the rashes, O;

Green grow the rashes, O;

The sweetest hours that e’er I spend,

Are spent amang the lasses, O.

There’s nought but care on ev’ry han’,

In ev’ry hour that passes, O:

What signifies the life o’ man,

An’ ’twere na for the lasses, O.

Green grow, &c.

The warly race may riches chase,

An’ riches still may fly them, O;

An’ tho’ at last they catch them fast,

Their hearts can ne’er enjoy them, O.

Green grow, &c.

But gie me a canny hour at e’en,

My arms about my Dearie, O;

An’ warly cares, an’ warly men,

May a’ gae tapsalteerie, O!

Green grow, &c.

For you sae douse, ye sneer at this,

Ye’re nought but senseless asses, O:

The wisest Man the warl’ saw,

He dearly lov’d the lasses, O.

Green grow, &c.

Auld Nature swears, the lovely Dears

Her noblest work she classes, O:

Her prentice han’ she try’d on man,

An’ then she made the lasses, O.

Green grow, &c.

One can practically see the yellow light at the window of the dance-hall and feel the pulse of romantic hope, a new and lively element in the blood. And here she is, Mary Morison – as ‘the dance gaed through the lighted ha’’ – and we are caught immediately in the drama of her specialness. There is a grave in Mauchline churchyard to ‘the poet’s bonnie Mary Morison, who died on 29 June 1791, aged 20’. Mary is a

ghost among the drinking glasses, yet forever alive in the flow of these images.

Mary Morison

O Mary, at thy window be,

It is the wish’d, the trysted hour;

Those smiles and glances let me see,

That make the miser’s treasure poor:

How blythely wad I bide the stoure,

A weary slave frae sun to sun;

Could I the rich reward secure,

The lovely Mary Morison!

Yestreen when to the trembling string

The dance gaed through the lighted ha’,

To thee my fancy took its wing,

I sat, but neither heard, nor saw:

Though this was fair, and that was braw,

And yon the toast of a’ the town,

I sigh’d, and said amang them a’,

‘Ye are na Mary Morison.’

O Mary, canst thou wreck his peace,

Wha for thy sake wad gladly die!

Or canst thou break that heart of his,

Whase only faute is loving thee!

If love for love thou wilt na gie,

At least be pity to me shown;

A thought ungentle canna be

The thought o’ Mary Morison.

I wrote part of my first novel, Our Fathers, in the west of Ireland, alone in a house by the sea in County Cork. After dark, a regular beam of light from the Fastnet lighthouse would fall over the bed and I woke there one night with a weathered thought. It was to do with the Irish who had left for Scotland years before. I went back to my desk and wrote some lines about the main character’s father, Tam. He ‘once wrote a letter to a cousin in Ireland, saying that he only stuck to the farm because of Robert Burns. “My habits are bad in the field,” he wrote, “but never mind, there’s something to see in the battle for stuff over here, with the thought of the poet’s hand there beside you.”‘ Tam then goes

to the Ayrshire madhouse at Glengall and sings ‘The Belles of Mauchline’ to his sick wife, and he kisses her.

The Belles of Mauchline

In Mauchline there dwells six proper young Belles,

The pride of the place and its neighbourhood a’,

Their carriage and dress a stranger would guess,

In Lon’on or Paris they’d gotten it a’:

Miss Miller is fine, Miss Murkland’s divine,

Miss Smith she has wit and Miss Betty is braw;

There’s beauty and fortune to get wi’ Miss Morton,

But Armour’s the jewel for me o’ them a’.—

A Night Out With Burns edited by Andrew O’ Hagan is published by Canongate, priced £9.99

Wigtown is Scotland’s Book Town, and is full of special bookshops. Shaun Bythell’s bookshop is now internationally famous thanks to his popular books The Diary of a Bookseller and Confessions of a Bookseller. Here he shares with us his life in lockdown.

Confessions of a Bookseller

By Shaun Bythell

Published by Profile Books

I never thought that I’d write these words (and I say this with what I can only describe as a nostalgic grimace), but I miss my customers. Not only do I miss them, I really miss them. Apart from the obvious fact that without them I have no income, I’ve finally realised that (and this time the grimace has become a wince – I can barely look at the screen as I type these words), I miss the social interaction of life in a bookshop. From the kind to the rude; from the friendly to the hostile, they provide me with material to write about, and a huge variety of conversations, most of which I would rather not have, but which I’m starting to crave. I’m fortunate to be locked down with my wife and our one year old daughter, so as silver linings go, I couldn’t have wished for more – although without the excuse of work, I’ve changed considerably more nappies than I normally would have done. Having a beautiful garden, and the most extraordinary spell of weather has also added a coat of sugar to the pill. I’ve built a sandpit, and we now have a paddling pool (mostly full of leaves) and I have ticked an embarrassingly small number of jobs both in the garden and the house off my ever growing list. But I miss the shop. I even miss Gillian the Ginger Menace, who works three days a week here, and spends most of her time and energy berating me for a litany of supposed inadequacies.

With the extraordinary weather, we should have been having barbecues with our neighbours and friends, going to the beach, and hillwalking, but even the absence of those opportunities has opened up others: every day we walk around Wigtown we try to find a new route. Incredibly, for such a small place, I’ve discovered things I didn’t know about. Restrictions on movement has meant that we’ve moved a lot more within our restricted area and learned to appreciate what we have. Other constraints have also revealed surprising unintended consequences. Having to queue outside the Co-op has often resulted in conversations with people with whom you would normally have a nodding acquaintance, but little more than than. When you’re standing near them on your socially distant strip of gaffa tape on the pavement, you find the time to learn more about them. A few weeks ago I started chatting to someone who I only know well enough that they inhabit that grey area between being an acquaintance and a friend, and discovered that he’d bought tickets for the Davis Cup (obviously couldn’t go) and that he’d been co-opted onto the board of the Wigtown Book Festival committee. He’s someone I’ve always liked, and I hope that I’m stuck in the queue beside him again soon.

Of course, there’s a dark humour to be found in these times too. Shortly afterwards, again in the queue for the Co-op, I was behind a Northern Irish woman called Chris. Sadly her husband is suffering from memory loss. There’s no humour in that of course, but she told me that one of her friends had seen a neighbour, a 75 year old woman who didn’t want to be seen visiting her equally aged neighbour by going through the front door, so instead she’d scaled a 6ft fence to have a lockdown cup of tea with her in the garden.

The customer who I most miss is Sandy, the Tattooed Pagan. He has been a regular visitor to the shop since I took over in 2001, and in that time we’ve become good friends. He lives alone, and has no mobile telephone, no computer, and never answers his landline, so when several people asked how he was (he’s in his 70s) I had no choice but to write to him. I didn’t know his address, but this being Galloway, an envelope with his name and a rough description of him found its way through his letterbox. I write letters to friends (and reply to some from strangers) every week – it is my preferred method of communication, so corresponding with him has not proved to be a challenge – in fact, it has been quite the reverse – almost as much of a pleasure as it is to see him in the shop. We’ve now exchanged three or four letters in each direction, and he recently sent me a poem about life in lockdown. Other correspondence from strangers continues, most of which comments upon how grateful I must be for ‘the internet’ as a means of selling my shop stock online while the shop is shut. But ‘the internet’ is now little more than Amazon when it comes to selling books online, and Bezos is not a devil with whom I’m prepared to sup. Even with a long spoon. I don’t sell online, and have no plans to do so ever again. My hubris may well finish me off financially.

Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell is published by Profile Books, priced £16.99

Denzil Meyrick is one of Scotland’s bestselling crime writers, and has just released the 8th novel in his DCI Daley series, set in Kintyre. Before catching up with the latest thriller, we asked Denzil about his favourite books.

Jeremiah’s Bell

By Denzil Meyrick

Published by Polygon

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

My granny was the first person I remember reading to me. I can still see picture books called Mary Mouse, Rupert Bear and Barbar the Elephant. When I got to the stage of reading myself in the late sixties/early seventies, I began to read Enid Blyton – like so many others of my vintage.

I was lucky to have access to the wonderful children’s books by Kintyre Author Angus MacVicar. Much of his work was set in Kintyre in the past, present, or future. He also described places that sounded very like where I lived, though they were fictional. I remember thinking what a good idea that was.

From memory, my overwhelming feeling at being able to read was one of the thrill of independence and discovery. I still have that feeling to this day.

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your latest book Jeremiah’s Bell. Is there something in particular you’re setting out to explore?

Jeremiah’s Bell is a study of family dynamics over a period of many years. Of course, being a DCI Daley novel, the family are dysfunctional in the extreme, and live a rather isolated and unusual life. Add a colourful history, and barbaric behaviour, and the circle is complete.

I suppose I’m saying that grudges and bad feeling can last for many years within an extended family unit. In some cases for generations. Also, patterns of behaviour can be replicated by members of a particular family, even though they may never have met, and are separated by many years.

It’s a tale of greed and revenge, where almost nobody is how they seem at first sight.

The book as . . . object. What is your favourite beautiful book?

I have an old leather-bound Bible with my late mother’s initials stamped on the cover. It’s moving in all sorts of ways.

Some of my most prized books are a pair signed by the late, great Iain Banks, gifted to me by my publisher. He was a fabulous, imaginative and original writer. Sadly gone too soon; but what a body of work he left behind.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

It’s so hard to pick one book; there are so, so many I’ve read that have shaped my life, and the way I think of existence and the human condition. Having said that, Farewell to All That by Robert Graves is a moving and unforgettable book. Within its pages both the best and worst of human nature is portrayed.

Like all great books, you can revisit it again and again and always find something new.

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson. My granny, Margaret Pinkney, nee Macmillan read it to me when I was perhaps four years old. I can still see the cover.

She was the Dux of the tiny country school in Kintyre she attended. Her father worked as a shepherd and cowhand. She had to trudge for miles backwards and forwards every day across the hills just to get to school. Now, she would likely have attended university, but in those days from her humble background, that wasn’t possible. Sent to service in Hull as a teenager, she became the chef to the city’s Lord Mayor. With my grandfather and my mum, they returned to Kintyre during the war to avoid the horrors of the blitz. Every time I think of Treasure Island, I think of her.

I very much doubt I’d have become a writer had it not been for her influence.

The book as . . . entertainment. What is your favourite rattling good read?

I’m going to pick two series of books, here.

First, the wonderful Flashman books by George MacDonald Fraser. Here we have the arch-cad from Tom Brown’s Schooldays, grown up and soldering his way through the battles of the Victorian era, but having lost none of his venality. Great writing, that is both funny and informative. The author’s attention to detail as far as the historical elements of the books are concerned is on the button.

Then there’s the Aubrey/Maturin series by Patrick O’Brian. These books are set in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic wars. O’Brian recreates the wooden world of a man-of-war with stunning clarity and compelling storytelling, in all its complexity. Like the Flashman books, these are easily dismissed as tales of adventure. But they are so much more; beautifully written and inspirational works, brimming with invention and more than a touch of humour.

Brian Scott and Hamish owe a debt of gratitude to them both.

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

In the Court of the Red Czar by Simon Sebag Montefiore takes us to Russia during the height of Stalin’s power and cruelty. Here’s a huge nation, where almost nobody – including the dictator’s family – is safe. It’s harrowing stuff, history in the raw, rather than fiction.

I’ve been fascinated by Russia since school. This book brought the horrors of the Gulag and Stalin’s infamous purges to me in all their grim reality. A masterful recreation of a time and place I’ll never see – thankfully.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

I’ve just finished reading Hilary Mantel’s brilliant trilogy based on the world of Thomas Cromwell in the court of Henry VIII. Right now, it’s hard to imagine reading another book – follow that! But I’m looking forward to continuing to work my way through Robert A Caro’s forensic account of the life of LBJ. Another step back in time, but so much to say about the present, and why America is the country it is today.

However, I’m always looking forward to discovering new books and writers. Reading is indeed a habit of a lifetime.

Jeremiah’s Bell by Denzil Meyrick is published by Polygon, priced £8.99

Wigtown Festival’s artistic director, Adrian Turpin, makes a great case for the South-West to be considered as Scotland’s literary heartland.

‘I fixed on Galloway as the best place to go,’ Richard Hannay declared in The 39 Steps. We liked the quote so much at the Wigtown Book Festival that we put it on a bag, and it’s come to mind a lot recently. For the past two years, we’ve been part of an EU-funded project looking at new approaches to literary tourism in rural areas. How can we make Dumfries & Galloway the best place to go for readers – even those not on the run from shadowy criminal conspiracies?

There’s a delicious variety in the Spot-lit project. In eastern Finland, plans are afoot to bring the wonderful (and undoubtedly) weird national epic Kalevala to a wider audience. Our partners at Arts over Borders in Northern Ireland dream of Enniskillen becoming a destination for Oscar Wilde pilgrimage. Meanwhile, along the Wild Atlantic Way, the storytellers and poets of Ireland’s West will be celebrated through new performances.

So what about south-west Scotland? What have we got to offer? More than is sometimes acknowledged. But that’s no surprise: Dumfries & Galloway (D&G) is used to being overlooked.

Let’s start with the classics. Burns’s Birthplace in Alloway often gets the glory, but it was Ellisland Farm outside Dumfries where he wrote “Tam o’ Shanter” and “Auld Lang Syne”, the town’s Globe Inn where he drank and St Michael’s Churchyard where he died. Walter Scott is about as Borders as you can get. But D&G might lay imaginative claim to Old Mortality, Redgauntlet and even The Bride of Lammermoor, which transposes its central story from Baldoon Castle, a stone’s throw from Wigtown itself.

Throw a stone in the south-west and you are likely to hit a place with a literary connection, be it Thomas Carlyle’s Ecclefechan or Hugh MacDiarmid’s Langholm. Four John Buchan novels are set in Galloway, while Peter Pan Moat Brae House – whose gardens fired the imagination of a young JM Barrie – is now home to Scotland’s National Centre for Children’s Literature.

Daundering along the Solway, one might note the Kirkcudbright of Dorothy L Sayers and Gavin Maxwell’s Elrig. And, at the risk of sounding like a particularly fiendish round of Stuart Kelly’s Literary Pub Quiz, did you know that John Ruskin’s family came from Wigtownshire? Or that Edgar Alan Poe wrote “The Raven” in Newton Stewart? I could go on.

A bit of literary trivia is always fun. But there is a serious point here. These literary landscapes offer real possibilities for sustainable tourism in south-west Scotland. It’s been done before: Samuel Crockett arguably invented Galloway as a Victorian tourist destination, through his bestselling but now forgotten novels.

As Scotland’s National Book Town Wigtown also has sold itself on books for more than two decades now – which explains why we took part in Spot-lit and are now working with nine businesses in Dumfries & Galloway as they develop new literary tourism experiences. These range from tours and stays to a musical performance and two new festivals. Since the Covid crisis, the project has taken on new significance as rural communities and tourist businesses begin to contemplate the road to recovery.

As several of these businesses show, literary tourism is not always the same thing as literary heritage. Vibrant festivals, independent bookshops (of which there were at last count 37 across the south of Scotland) and living writers, such as D&G-based Stephen Rutt, Patrick Laurie and Shaun Bythell, are all a vital part of the package.

‘Scotland’s Literary Heartland’ has a nice ring to it, and, though it would be nice to claim that title for D&G, it would be a push. But extend the parameters a little, north into Ayrshire and east into the Borders, and it looks less like hyperbole. From Alloway to Abbotsford, via Auchinleck and Melrose, literary pearls lie tantalising across the south of Scotland. Now is the time to make a necklace of them.

Patrick Laurie has written a beautiful book, Native: Life in a Vanishing Landacape, on his life on his family’s farm in Galloway. Here, he shares with us his thoughts on the place he calls home.

Extract taken from Native: Life in a Vanishing Landscape

By Patrick Laurie

Published by Birlinn Ltd

Galloway is unheard of. This south-western corner of Scotland has been overlooked for so long that we have fallen off the map. People don’t know what to make of us anymore and shrug when we try and explain. When my school rugby team travelled to Perthshire for a match, our opponents thumped us for being English. When we went for a game in England, we were thumped again for being Scottish. That was child’s play, but now I realise that even grown-ups struggle to place us.

There was a time when Galloway was a powerful and independent kingdom. We had our own Gaelic language, and strangers trod carefully around this place. The Romans got a battering when they came here, and the Viking lord Magnus Barefoot had nightmares about us. In the days when longboats stirred the shallow broth of the Irish Sea, we were the centre of a busy world. We took a slice of trade from the Irish and sold it on to the English and the Manxmen who loom over the sea on a clear day. We spurned the mainstream and we only lost our independence when Scotland invaded us in the year 1236. Then came the new Lords of Galloway and the wild times of Archibald the Grim, and he could fill a whole book himself.

The frontier of Galloway was always open for discussion. Some of the old kings ruled everything from Glasgow to the Solway Firth, but Galloway finally settled back on a rough and tumbling core, the broken country which lies between tall mountains and the open sea. This was not an easy place to live in, but we clung to it like moss and we excelled on rocks and salt water both. We threw up standing stones to celebrate our paganism, then laid the groundwork for Christianity in Scotland. History made us famous for noble knights and black-hearted cannibals. You might not know what Galloway stands for, but it’s plain as day to us.

We never became a county in the way that other places did. Galloway fell into two halves: Wigtownshire in the west and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright in the east. There are some fine legal distinctions between a ‘Shire’ and a ‘Stewartry’, but that hardly matters anymore because both of them were deleted in 1975 when the local government was overhauled. The remnants of Galloway were yoked to Dumfries, and the result is a mess because Dumfries and Galloway are two very different things.

Dumfriesshire folk mistake their glens for dales and fail to keep Carlisle at arm’s length. They’re jealous of our wilderness and beauty, but we forgive them because it’s unfair to gloat. Besides, they have the bones of Robert Burns to console them, and don’t we all know it. Perhaps Dumfriesshire is a decent enough place, but we’ve pulled in different directions for too long to make an easy team. Imagine a county called ‘Perth and Fife’ or ‘Carlisle and Northumberland’. Both would be smaller and more coherent than ‘Dumfries and Galloway’. Now there are trendy councillors who abbreviate this clunky mouthful to ‘D ’n’ G’, as if three small letters were enough to describe the 120 miles of detail and diversity which lie between Langholm and Portpatrick. Tourism operators say we are ‘Scotland’s best-kept secret’, and tourists support that claim by ignoring us.

It’s easy to see why visitors rarely come. They think we’re just an obstacle between England and the Highlands. They can’t imagine that there’s much to see in the far south-west and tell us that ‘Scotland begins at Perth’. Maybe it’s because we don’t wear much tartan, or maybe it’s because we laugh at the memory of Jacobites and Bonnie Prince Charlie. Left to our own devices, we prefer the accordion to the pipes and we’d sooner race a gird than toss a caber. If you really want to see ‘Scotland’, you’ll find it further north.

When Galloway folk speak of home, we don’t talk of heather in bloom or the mist upon sea lochs and mountains. Our place is broad and blue and it smells of rain. Perhaps we can’t match the extravagant pibroch scenery of the north, but we’re anchored to this place by a sure and lasting bond. There are no wobbling lips or tears of pride around these parts; we’ll leave that sort of carry-on to the Highlanders. We’ll nod and make light of it, but we know that life away from Galloway is unthinkable.

My ancestors have been in this place for generations. I imagine them in a string of dour, solid Lowlanders which snakes out of sight into the low clouds. These were farming folk with southern names like Laidlaw and Mundell, Reid and Gilroy, and they worked the soil in quiet, hidden corners without celebrity or fame. Lauries don’t have an ancestral castle to concentrate any feeling of heredity. We’ve worked in a grand sweep between Dunscore and Wigtown and now all of Galloway feels like it might’ve been home at one time or another. I was born to feel that there is only one place in this world, and I can hardly bear to spend a day away from it. Satisfaction alternates between quiet peace and raging gouts of dizzy joy.

Our friends at Garmoran Publishing have just released an anthology of short stories and poems from both established and up-and-coming names in UK and US writing. With works across all genres – comedy, crime, fantasy, history, there’s a story for all tastes. All proceeds from this anthology will be donated to The Ambulance Staff Charity, making it an essential purchase to support our essential workers. Here, we share a story from one of the anthology’s editors, Hayleigh Barclay.

‘Rolling it In’ taken from Stories from Home