We present a visual celebration of the fourth annual Kelpies Design and Illustration Prize Award Ceremony which took place at Creative Exchange in Leith, Edinburgh, in March.

Leith’s Creative Exchange is busy with Ceremony attendees

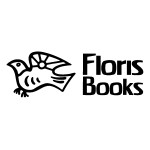

Winner Aimee Ferrier with Elizabeth Ezra, author of Ruby McCracken: Tragic Without Magic

The 10 very talented shortlisted designers

Aimee Ferrier and Elizabeth Ezra in front of the winning design

The 10 shortlisted cover designs

And last but not least the winning design by Aimee Ferrier

The fourth annual Kelpies Design and Illustration Prize Award Ceremony took place at Creative Exchange in Leith, Edinburgh, on Thursday 30th March. Designers were asked to create a book cover for debut author Elizabeth Ezra’s Kelpies Prize-winning novel Ruby McCracken: Tragic Without Magic. The winner will go on to work with the Floris design team to create the final cover for the book.

Congratulations to all the highly talented ten shortlisted designers. The Highly Commended prize went to Nataša Ilinčić, a designer based in Edinburgh, and the People’s Choice award went to Grisel Miranda for the second year running. First prize went to Aimee Ferrier, a student at Edinburgh College.

Interested in entering the 2018 Kelpies Design & Illustration Prize? Check details in this piece by Floris Books.

You can also find out more about the Kelpies Prize in this article on Books from Scotland by Chani McBain.

Reflecting on her own childhood, author Kathrine Sowerby considers how her new novel The Spit, the Sound and the Nest was shaped by her own memories as well as the voices of her central protagonists, teen runaways Felix and Luc, as they navigate the complex world around them.

A Book of Beginnings

By Kathrine Sowerby

The Spit, the Sound and the Nest is a book of three stories connected by coastal locations, an overriding theme of birth; the fear, wonder and risk that surrounds new beginnings at any stage in life, whether through choice or circumstance. And the decisions that we make, collective or private, that affect the lives of others.

Anything is possible, as teen runaways, Felix and Luc, find out when they are invited to stay with a grieving couple, Rita and Joseph, on a remote stretch of land that they have all escaped to for different reasons.

“Stepping out from the curtains of trees, they stood centre stage with the sea and sand for an audience. They drank in the bays and capes before them: folds and folds of snow-covered sand, mountains of it, and not a single person in sight.”

I wrote the stories when my three children were very young in whatever hours I could claim and a few years on, now the book is published, I see myself looking through the eyes of my characters at possibilities and landscapes far from my domestic life. Like Rita, conjuring memories.

“The window was covered in condensation and she wrote a name with her fingertip, watching the drips from the letters run down the windowpane and collect on the sill.”

And Helle, who arrives soaking wet at the door of Echo’s caravan in the woods with her new born baby trying to piece together the events that have led her there. Echo finds herself turning to her estranged husband, Peter, for help as the interruption to her solitary life causes Echo to face both her past and her future.

“She looked at the black-and-white diagram of lichen tissue. Earlier it had reminded her of a congested coastline with roads, railway tracks and tunnels crossing over one another, jostling for space. Looking again she saw the cells born from the tangle, the inevitability of expansion.”

The locations of the stories go unnamed but are a patchwork of formative places in my life – Slovakia and Lithuania where I lived and worked in my early twenties, the dunes and forests of North East Scotland, and my grandparent’s house in South Africa that I visited as a child, at the same curious age as Edna with her kingfisher that she saves with the help of gardener, Isaac.

“He lifted the cloth from the box and the bird splayed its wings. It scrabbled around on the smooth base of the box; Isaac gently tipped the box and it slid on to the ground. It flapped its wings against the dust.”

And Alice, who takes the role as the protective older sister as she and Edna try to make sense of the adult world when their parents go on holiday leaving them in the care of the housekeeper, Magdalena.

“Everything they had tied and fastened together came undone and floated out to sea with Alice and Edna clinging on, waiting to be rescued.”

My own children are older now and, like my characters, they are finding that life is a series of beginnings, which can be both exciting and scary. I think of pine trees planted to give strength and stability to shifting sands and, even then, the vulnerability of roots. Life is unpredictable and beginnings often come when we least expect them. Doors open, inviting us to cross their threshold and see what’s on the other side.

The Spit, the Sound and the Nest by Kathrine Sowerby is out now published by Vagabond Voices priced £10.95.

In this exclusive article Robert J Harris explains how he approached writing about Arthur Conan Doyle as a twelve year old – Artie – in his inventive new novel The Gravediggers’ Club. Researching original material such as Conan Doyle’s autobiography and letters from his younger years, Harris was mindful of the need to balance an accurate portrayal while being true to the tropes of children’s literature whereby, as he acknowledges, it is ‘important that the young hero should be the one who wins the victory over the villains’.

Writing for the Young Protagonist

By Robert J Harris

The twelve year old Arthur Conan Doyle as the hero of The Gravediggers’ Club

The Gravediggers Club, a youthful adventure of the young Arthur Conan Doyle, was originally conceived as a follow up to my two novels about the youthful adventures of Leonardo da Vinci and Will Shakespeare. In each case it was important to me that the character should not be merely a miniaturised version of the adult. My teenage Leonardo would not be inventing flying machines and painting perfect pictures. Young Will would not be reeling off plays and sonnets. I was attempting to give an accurate portrayal of what my young protagonist would be like, based on what little information we have and on my own sense of character.

In the case of Conan Doyle our main sources are his own autobiography and a number of letters he wrote home during his schooldays, from which we can picture a boisterous, imaginative youth, with a love of sport and adventure. He is no brilliant teller of tales, and he is definitely not a detective in the Sherlock Holmes mould. Yet, as with my other two protagonists, part of the fascination of the story is seeing him take the first steps on the road to becoming the man he will be.

There are also a number of general points to be borne in mind when the hero of an adventure has barely reached his teens. The young hero has two main disadvantages compared to an adult hero.

Firstly he has no status or authority and so requires a high degree of cleverness and boldness to achieve his aims. There are places he is not allowed to enter, so he must use trickery or disguise to gain access. In the novel Artie gains entrance to an illegal gambling den by pretending to be a replacement for a servant who has called off sick. This means he is always in danger of discovery, which adds suspense to the scene.

Robert Harris

He also has no right to question people who might have information. Therefore his questioning must be represented as for some innocent purpose, as when Artie questions a gravedigger pretending that his friend Ham is interested in a possible career in this profession. This results in much comic fun.

The second main disadvantage is that our young hero cannot physically outmatch the villains when, as in this case, they are all ruthless adults. If it comes down to a battle of strength and numbers the villains must inevitably win. The advantage for the hero is that the villains will inevitably underestimate him, plus his smaller size makes him elusive. To win the day over his more powerful opponents, he must be clever, resourceful and bold.

It is important that the young hero should be the one who wins the victory over the villains. It is disappointing if towards the end of the story our young hero is captured and adults must show up to rescue him. He should at least have pulled off a stalemate against the villains before the police arrive to arrest them.

Ultimately it is moral courage as much as physical courage that wins the day for our young heroes, and also the strength of their friendship. In many ways it is Ham who becomes the true hero of the story, overcoming his basic disinclination to become involved in such a hairbrained adventure. But to discuss the role of the ‘stalwart companion’ would require a whole other article.

Robert J. Harris is the author of The World’s Gone Loki trilogy and Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers’ Club, both published by Floris Books.

Street Song by multi award-winning Irish author Sheena Wilkinson is one of the first titles to kick off the new Young Adult fiction imprint Ink Road. In this extract we meet 18-year-old RyLee whose career as a teen pop sensation is over after battles with addiction and constant media scrutiny. Can he put his life back on track or will the past catch up with him?

Extract from Street Song

By Sheena Wilkinson

Published by Ink Road

I woke early – it had been a weird night even by our standards; we’d passed out mid-fight – and there was Kelly, curled round my duvet with her back to me. Her hair, all smoke and hairspray, clogged my mouth, and through the thin sweaty cotton of her green top you could count each of her vertebra. I stretched out my finger and placed it between two of the green cotton bumps and shuddered. She whimpered and wriggled and turned round. Her eyelids cracked open the layers of mascara and eyeliner.

‘Ryan?’ she murmured. ‘Iss not morning?’

I shook my head. I couldn’t trust myself to speak because when she opened her mouth I caught a reek of last night’s vomit, drink, smoke and, somewhere in the mix, the pizza we’d had on the walk between the pub and the club – she only ate when she was stoned. I half-turned my head away and focused on the far corner of my bedroom. The cold dawn light slanting through the slats of the wooden blind showed the dust on my guitar. If I looked above it I’d see the photo of me the night I won PopIcon, but I didn’t look up.

Kelly smiled dopily and reached her hand out towards me.

I drew away. ‘You have to go.’

Her face crumpled.

‘I said last night – I can’t do this any more.’

‘Ry.’ Her eyes widened. ‘We were both out of it last night. We both said things we didn’t mean.’

I had no idea what she’d said. She’d been talking all summer and I’d stopped listening about the start of August. I just knew that her cold thin fingers on my skin made me cringe.

And she’d called me Ry.

‘You have to go now.’

If she stayed another minute I’d hurt her. I’d tell her she disgusted me, that I hated who I was with her. That if I didn’t get rid of her I would lose myself. Again.

‘Is it the drugs? Because I only—’

‘It’s not one thing.’ I fell back on clichés. ‘It’s not you. We had a laugh, OK? But it’s over.’

Clichés and lies. We’d never had a laugh. Kelly wasn’t a laughy kind of girl. Maybe at the start, when she was a bit starry about me. I’d liked that – the flattery. And her friends were cool.

She cried and fussed and clawed at me and went out and locked herself in the loo for ages and came out all shiny-eyed and, God, it was boring. By the time I got her bundled out into the road, sobbing and yelling and calling me all kinds of names, I felt as knackered as I used to feel coming off stage, only without the buzz. I pushed the heavy front door to and took a second to lean against it, eyes closed in relief, breathing in the quiet, the glossy white paint cold against my bare arms.

‘Ryan?’

I opened my eyes to see my mother. ‘Hi, Louise.’

She frowned, then stopped as if remembering that Ricky always told her it made her look older. Dark roots showed in her long blonde hair. That wasn’t like her. I suppose I hadn’t seen her for a few days. I’d been staying out, different places, mates’ floors, Kelly’s bed; one night a few of us sat up all night on the beach, drinking and having a laugh. Kelly’s mates. I’d have to make new ones now.

‘What was all that row?’

I shrugged. ‘Kelly just left.’

‘Was that shouting I heard?’

‘How do I know what you heard?’

‘Ry.’

‘Don’t call me that.’ I tried to push past her, but she blocked me with her arm. She was wearing a peachy satin dressing gown, and her bony wrist poking out reminded me of Kelly.

‘Did you upset that poor girl?’

‘We broke up.’

‘Ah, Ryan. She was lovely.’ Louise and Kelly had done a lot of girly bonding over hair extensions and calories. ‘What did you do to her?’

‘Nothing. She had issues. I can’t stand girls like that.’

‘Jesus, you’re a little bastard.’ She shook her head. ‘Poor girl.’

‘She was a bad influence, Mam.’ She loved it when I called her Mam. ‘I didn’t want to worry you by telling you this but, she was using – stuff. I couldn’t trust myself around her. You know I don’t want to get back into all that.’ I put a little crack in my voice, the kind of crack no mother could resist.

Street Song by Sheena Wilkinson is published on April 20th by Black & White Publishing priced £7.99 as part of their new Young Adult fiction imprint Ink Road.

If you enjoyed this extract you might also like this introduction from The Jungle by Pooja Puri, the first book to be published on the Ink Road imprint.

In this zany extract from new Young Adult novel Spontaneous by American author Aaron Starmer we hear about how it all started with Katelyn Ogden’s spontaneous combustion at school. Was Katelyn’s terrible death a one-off fluke or will more students blow up without warning or explanation?

Extract from Spontaneous

By Aaron Starmer

Published by Canongate

How It Started

When Katelyn Ogden blew up in third period pre-calc, the janitor probably figured he’d only have to scrub guts off one whiteboard this year. Makes sense. In the past, kids didn’t randomly explode. Not in pre-calc, not at prom, not even in chem lab, where explosions aren’t exactly unheard of. Not one kid. Not one explosion. Ah, the good old days.

Katelyn Ogden was a lot of things, but she wasn’t particularly explosive, in any sense of the word. She was wispy, with a pixie cut and a breathy voice. She was a sundress of a person — cute, airy, inoffensive. I didn’t know her well, but I knew her well enough to curse her adorable existence on more than one occasion. I’m not proud of it, but it’s true. Doesn’t mean I wanted her to go out the way she did, or that I wanted her to go out at all, for that matter. Our thoughts aren’t always our feelings; and when they are, they rarely last.

On the morning that Katelyn, well, went out, I was sitting two seats behind her. It was September, the first full week of school, an absolute stunner of a day. The windows were open and the far-away drone of a John Deere mixed with the nearby drone of Mr. Mellick philosophizing on factorials. Worried I had coffee breath, I was bent over in my seat, digging through my purse for mints. My POV was therefore limited, and the only parts of Katelyn I saw explode were her legs. Actually, it’s hard to say what I saw. Her legs were there and then they weren’t.

Wa-bam!

The classroom quaked and my face was suddenly warm and wet. It’s a disgusting way to say it, but it’s the simplest way to say it: Katelyn was a balloon full of fleshy bits. And she popped.

You can’t feel much of anything in a moment like that. You certainly can’t analyze the situation. At least not while it’s happening. Later, the image will play over and over in your head, like some demon GIF, like some creeper who slips into your bed every single night, taps you on the shoulder, and says, “Remember me, the worst fucking moment of your life up to this point?” Later, you’ll feel and do a lot of things, but when it’s actually happening, all you can feel is confusion and all you do is react.

I bolted upright and my head hit my desk. Mr. Mellick dove behind his chair like a soldier into the trenches. My red-faced classmates sat there in shock for a few moments. Blood dripped down the windows and walls. Then came the screaming and the obligatory rush for the door.

The next hour was insane. Hunched running, hands up, sirens blaring, kids in the parking lot hugging. News trucks, helicopters, SWAT teams, cars skidding out in the grass because the roads were clogged. No one even realized what had happened. “Bomb! Blood! Run for the fucking hills!” That was the extent of it. There was no literal smoke, but when the figurative stuff cleared, we could be sure of only two things.

Katelyn Ogden blew up. Everyone else was fine.

Except we weren’t. Not by a long shot.

Spontaneous by Aaron Starmer is published by Canongate on May 4th priced £7.99.

Voyage into outer space with this fun adaptation of Edwin Morgan’s science fiction poem The First Men on Mercury, first published in 1973, produced here by Glasgow-based designers Metaphrog and educational charity ASLS.

This comic adaptation of Edwin Morgan’s The First Men on Mercury, by Glasgow-based design duo Metaphrog, was commissioned as part of an ASLS initiative to mark National Poetry Day in 2009. A learning and teaching resource for Scottish schools, it is reproduced here with kind permission.

David Robinson delves into the fantastical world of Young Adult fiction by casting an eye over Dragon’s Green, the hotly anticipated first Young Adult novel by acclaimed author Scarlett Thomas. With narrative action centered around the Tusitala School for the Gifted, Troubled and Strange and the mysterious Otherworld, David finds Dragon’s Green to be magical and metafictional but – above all – an energetic and imaginative celebration of books and reading.

David Robinson Reviews: Dragon’s Green

By Scarlett Thomas

Published by Canongate

“The most exciting debut in children’s fiction since Harry Potter.” No, I’m not going to count the number of children’s writers who have been saddled with such weighty hype. It wouldn’t be fair. There are too many of them, and the publicity bubble always bursts at the bookshop till.

But that’s precisely the quote on the back of Scarlett Thomas’s Dragon’s Green, published this week by Canongate. So why am I writing about it? Have I learnt nothing about the yawning emptiness of hype?

I’ll begin with the name of the person making the claim: Joanne Harris. And that carries some weight with me. Firstly, because she’s nothing to do with Canongate. Secondly, because Harris, who once spent 22 hours recording Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire on audiotape as a Christmas present for her daughter, knows the full extent of Rowling’s grip on the young teen mind. And finally, because she’s no slouch at fantasy herself.

Most people know Scarlett Thomas as the geek chic or ultra-metafictional author of books such as PopCo and The End of Mr Y, just as they’ll know Harris as the author of Chocolat. But just as Thomas is now flexing her muscles as a Young Adult writer with Dragon’s Green, Harris did the same thing back in 2007 with her novel Runemarks, the first of a trilogy, and which is out in paperback this month from Gollancz.

The final parallel between the two writers is that, when they switched to YA fantasy fiction, they both drew extensively on their own obsessions. With Harris, it was Norse mythology. She has been writing stories about the Norse gods since she was nine and a friend of her parents gave her a present of a 1919 copy of HA Guerber’s lavishly illustrated Myths of the Norsemen. The interest has been lifelong: these days, she is even learning Old Norse. (Incidentally, the hold of the Norse gods on our imagination hasn’t waned either; the first of the eight-part TV adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s 2001 novel American Gods – in which the old Norse gods tackle their 21st century rivals such as wealth and the media – is screened by Starz in the US at the end of this month).

With Thomas, the key obsession is with storytelling. Dragon’s Green is drenched in it. Books are the key to all of its adventures. Through books, characters can – literally – get lost, just as they could in The End of Mr Y. Through books, as those agencies promoting reading always promise, you really can travel in your head to other places, only this time your body will go with you. One of the Thomas’s neatest ideas is that the last-ever reader of a book can gain immense power from doing so. Why? It’s pure Derrida:

“You know when you read a book that’s set in a big house and you get a description of the house, but your imagination makes up its own description anyway? And if you think about it, the house you picture is actually somewhere you visited when you were five, or your neighbours’ place or something like that? Books are used to having their meanings shaped in these ways by readers. […] If ten thousand people all read a book and love it, and add their descriptions, locations and feelings and so on, a book absorbs all that energy and becomes extremely powerful. The Last Reader of that book will have a particularly strong experience of it and at the end he or she will absorb all of that power […]”

The last copy of Dragon’s Green is one such book full of latent energy from all its past readers. If Effie Truelove, a pupil at the Tusitala [geddit?] School for the Gifted, Troubled and Strange, can summon up its powers, it will be able to take her to the Otherworld, the world of true magic, and – who knows? – meet her mother there. Or maybe her beloved grandfather. Or maybe neither. I’m not telling.

It helps that Thomas has uninvented the internet (there’s a dark net equivalent for scholars of magic, but effectively we’re back to books as a source of all knowledge). There are some computer arcade games too, but they’re hardly enticing: people play them “until their life force runs out”. But essentially this storyland is a bibliophile’s paradise, and if you’re lucky enough to wear the Spectacles of Knowledge – I imagine they must be something a bit like Google Glass – you can wander around a library and tell, by green-and-gold bars emanating from each book which of them has the most magical power. And libraries matter – especially one, as here, that is full of magic books. Indeed, the whole plot is essentially about the recovery of a library, which is a new one on me.

What kind of reading would the Spectacles of Knowledge give for Thomas’s own book? Quite a high one, I reckon. Right from the start, with its description of a particularly scary teacher, Mrs Beathag Hide, there’s a subversive unpredictability about her writing. After emphasising the teacher’s scariness (“the kind of teacher who gives children nightmares”, “face as pale as a cold moon”) we are told “Her perfume smelled of the kind of flowers that you never see in normal life, flowers that are very, very dark blue and only grow on the peaks of remote mountains, perhaps in the same bleak wilderness as the tree whose twigs her fingers so resembled.”

Already, you get a flavour of Thomas’s style. It’s never obvious. And even suppose we DID think of what perfume such a character would wear, we probably wouldn’t imagine such further extensive qualifications about its source. No, we would stick at the most basic levels of description. Instead of which:

“Just her voice was enough to make some of the more fragile children cry” – again, most descriptions of incidental characters in children’s books would end there, but Thomas’s rolls on baroquely – “sometimes only from thinking about it, late at night or alone on a creaky school bus in the rain”. By the time you’ve reached “in the rain” – the fourth qualifier in the sentence – you realise that, even though you’re only on Page 2, you’re going to enjoy Dragon’s Green. To parents of a certain vintage, it’s akin to that moment when you sat down to watch Toy Story with your kids and realised that there are going to be laughs there for grown-ups too.

But that not enough to answer whether Dragon’s Green is going to live up to the Harry Potter hype. For that, you’ve got to reach back into your own mind when you were a teenager and remember what you most needed from a book. This is where it’s important to mention that in Dragon’s Green, Effie Truelove isn’t acting alone, but has two boys and two girls in her class to help her. Whether or not Thomas’s readers believe in their friendship is probably what will determine the success of her book. Why? Because that’s the main reason Harry Potter worked for JK Rowling. “If you put all the Quidditch and magic aside,” Charlie Fletcher, the Inveresk-based screenwriter and author of The Oversight fantasy trilogy told me, “the Harry Potter books were essentially very traditional and about friendship and loyalty and forming your own family beyond the one you’re born into. That’s the key for teens, because you’re leaving your own family behind and making an alternate family with your friends.”

Children’s book expert and literary agent Lindsey Fraser agrees: “Those three central characters in Harry Potter – their friendship is what children instantly recognise; that’s what the big hook is. I used to think that love in its widest sense was the driving force in all children’s fiction, but now I think it’s all about trust. From trust flows confidence and bravery, so you can take risks and sometimes be reckless and stupid and not always do the right thing, but you won’t be blamed for it. So you can go outside your comfort zone – and that’s what children’s books are all about.”

As Dragon’s Green is only the first volume in Thomas’s Worldquake series, I don’t yet know to what extent it will live up to all that. But she is, I think, off to a hugely promising start.

David Robinson is a freelance journalist and editor and from 2000-2015 he was books editor of The Scotsman.

Dragon’s Green, book one in the Worldquake series, by Scarlett Thomas is out now published by Canongate priced £12.99.

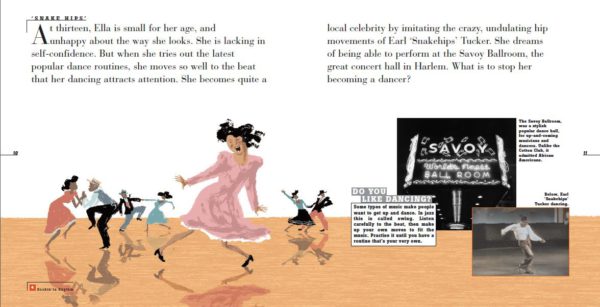

Extract from Ella Fitzgerald

Ella Fitzgerald by Stephane Ollivier and Remi Courgeonis is out now for children aged between 7 and 10 published by Moonlight Publishing as part of the First Discovery series. Priced £15.95 this includes an accompanying CD which features 13 of the singer’s most emblematic recordings alongside the book’s narrative.

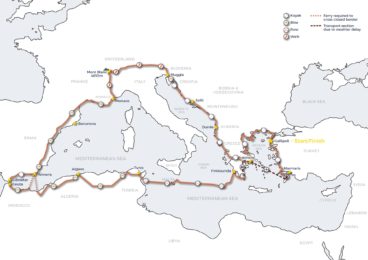

Extract from Mediterranean: A Year Around a Charmed and Troubled Sea

By Huw Kingston

Published by Whittles Publishing

Change of Direction: Attempting to Outrow an Approaching Winter Storm

Huw Kingston

March 2015

We saw few fish jumping or wildlife of any description; just us, the sea and occasional passing ships. A tiny bird rested briefly on an oar, and I wondered when he had begun his journey and where he would be going to next. The open sea does not offer enough to nourish me, much less so than a desert. In the desert you can at least move all around. This row across the Mediterranean was a very special solution for the continuation of my journey but overall the monotony and continual motion ensured that it was primarily a physical and mental challenge rather than offering the satisfaction I derive from changing landscapes.

Then Jure warned of a change afoot. Of a very strong easterly wind change that would reach us before we reached Crete. A wind that would stop us dead in our tracks and send us scuttling, helpless, backwards, for three or four days at least. Jure, with the computer models and weather maps of all Europe at his disposal, had been wrong before and we hoped he would be this time. Wrong not through any fault of his own but through the sheer unpredictability of Mediterranean weather in winter. But if he was right there was no way we could reach Crete before the storm hit. Initially it was a throwaway line I used, like tossing a baitless hook into the sea: ‘Perhaps we should go north to the Peloponnese in Greece?’

Huw cooking up from the cabin on Mr Hops

Then on Thursday 5th, bad wind hit us and we paid out the para anchor again. For another 24 hours we were jolted left, right, left, right by waves. Every organ in my body was smashed against its neighbour in a cabin just too small for two. The wind was bad outside and in. I slept not a wink, everything ached. Then Marin announced a plan. This young man, possessed of fierce intellect and determination, had sketched out a ‘give it our all’ option to reach the Peloponnese. If Jure was right we might, just might, make it in time. But it was all or nothing, never mind the bollocks, every second counts rowing for 36 hours or so.

The wind swung in our favour so we hauled in the para anchor and began. But I had become lazy, my strokes insincere. With less than a half century of days to the end of my year-long journey I was thinking too much of that end. I was thinking of time back home with the family, of seeing a house that I had left as a half-renovated building site, now complete. Of the smells and sounds of the Australian bush.

Huw rowing at night in the rain

Marin was not blind to my tardiness and announced part-way through my dusk shift that once my shift was done he would row the next 24 hours alone to improve our chances of success. He then shut the hatch door to sleep. I was pissed off; angry that he had announced his intentions without any discussion, disbelieving that on his own he could do better than the two of us.

But I was indeed letting the team down and had no excuse. Marin had kicked me in the arse and I woke up to myself and our position. I rowed as hard as I could for the rest of that shift and, when Marin appeared again, told him that sure he could row alone but only if I could not match his speed or at least come close. He checked the distance covered that past hour, smiled and simply said, ‘Good job.’

Huw sleeping in the cabin of Mr Hops

We began to scrawl the distance covered per shift in red pen onto the inside of the cabin wall. H 4.3 miles, M 4.3 miles, H 4.6 miles, M 4.7 miles, H 5.1 miles, M 5.5 miles. We pulled on those oars like there was no tomorrow; we stuffed food into ourselves, we grabbed sleep… We pulled on those oars like there was no tomorrow; we stuffed food into ourselves, we grabbed sleep… We pulled…

Ten days out from Malta and land appeared, hung over by grey. Rain squalls began to hit us. We pulled… We planned one landing place then another as time and weather changed. The middle finger of the Peloponnese? No, not possible; it’ll be the most westerly one, Methoni, perhaps. Finally we took aim for tiny Finikounda and told Dimitris. He was just about to take the ferry from Athens to Crete to meet us with some of his supporters. Indeed some had already left for Crete to put the finishing touches to a meticulously planned welcome party; a party we were not going to show up at.

Mr Hops and a rainbow in Greece

Marin’s cogs and wheels whirred and ground, calculating drift, wind, what time that fucking easterly would hit that could mean all was in vain. He feverishly plugged new waypoints into the GPS, and as if to challenge him further our electronic compass said thanks and goodnight. Bastard! We pulled…

Darkness fell and the light show began. Clouds, blacker than the night, issued seashaking claps of thunderous applause first, before then opening their bladders to piss on us. Bastards! Hail, rain, cold. We pulled…

Conditions we liked but rarely got – a tailwind and a following sea

As we came toward small Venetiko island it was Marin’s shift. I peeled off soaked gear in the cabin and tried to warm up. Then I heard it amongst our tiny radio masts: I heard the whistle of a new wind. The wicked witch of the east had arrived. Bastard, bastard, bastard!! Soon the sea was up, and Marin, already 24 hours into this marathon, pulled ever harder toward the island. I shouted instructions: 2 miles, 1.7 miles, 1 mile… Another cloud dropped its load and waves broke on rocks nearby, unmarked on our chart: 0.4 miles… 0.3 miles… 0.2 miles… Mr Hops came around to turn up the lee of the island as the moon shed some light through a gap in the clouds. It was 8 p.m. and we were some 7 nautical miles from Finikounda.

The respite was temporary as we again felt the full force of the wind through the gap between island and headland. The moonlight went out, again. It was my turn, again. I squeezed Marin’s shoulder hard as we swapped places and he collapsed into the cabin. Still-tired arms pulled on the oars, wasted legs sprung lifelessly against the footplate. The wind blew us sidewards, but Mr Hops inched his way across the gap. I was certain that, once in the lee of the headland, all would be calm. But we were pushed further out from it. Progress was painfully slow: less than a mile in two hours. I tried to pull back toward the land but my resolve began to weaken. It was pouring rain again. It was Marin’s turn again. Better he sleep and stay dry than cop another soaking. I didn’t wake him and buckled down and rowed as hard as I had rowed before. Finally, finally, I found myself in water that was calm aside from the raindrops on its surface. I rowed another hour, before the realisation that all I was doing was dropping a blade in the water and pulling it straight out again made me call ‘10 minutes’. After four hours on the oars and with two miles to go, I climbed into the sleeping bag, wet clothing and all.

Huw’s Mediterranean route

As torches and headlights flashed from the wall of the tiny harbour of Finikounda, I exited my damp cocoon into a handshake offered by Marin: ‘It’s unbelievable what we have done, Huw.’ An hour later, or even less, we would not have been there, could not have beaten the storm. Many months later Marin told me that there was no way he could have rowed solidly to get us to the Peloponnese. That his words to me were meant to motivate me to pull my finger out. They had indeed.

Mediterranean: A Year Around a Charmed and Troubled Sea by Huw Kingston is out now published by Whittles Publishing priced £19.99.

The Island Below The Waves

By Jay Armstrong

Excerpt from Elementum Edition Two

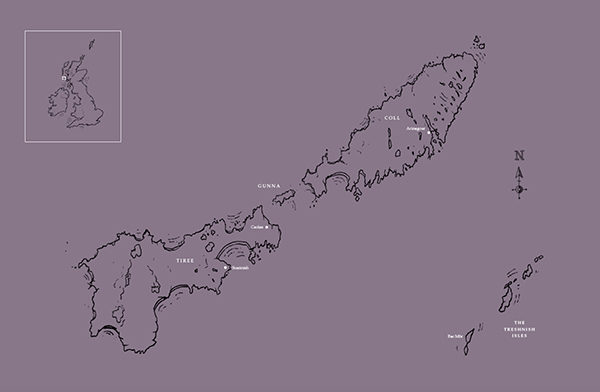

The Isle of Tiree (Gaelic – Eilean Tiriodh) is the most westerly of the Scottish Inner Hebrides. It is about ten miles long, five miles wide and mostly flat, with only three sizeable hills. Sail a few miles from its shores, from where only these hilltops are visible, and you can see why Tiree is known as tìr bàrr fo thuinn – ‘the island whose peaks lie below the waves’. In the winter months there are ferocious Atlantic storms, and with no woodland to buffer the gales, winds sweep across the island unchecked. These winds and waves however, have shaped the island’s history as much as its inhabitants and their dwellings.

A flint arrowhead, found in the dunes near Balevullin on the north-west coast of the island, suggests that hunter-gatherers arrived on Tiree as early as 12,000 years ago. They were seasonal visitors, however, and it would be another 6,000 years until the island was settled by Neolithic farmers, drawn to its fertile grasslands. This soft dune pasture, formed from the white windblown sand and rotted seaweed, stretches inland to the ‘blackland’ (where sand reaches the peat) and is known as machair, Gaelic for ‘low-lying, fertile plain’.

One of the rarest habitats in Europe, machair is found in northern and western coastal areas of Britain and Ireland. On Tiree, the machair is managed by the crofters who rotate cultivation and grazing. This style of farming encourages rare species of orchid to flourish and preserves the habitat of the migratory Corncrake (Crex crex). Careful and collaborative stewardship of the island maintains these diverse habitats and there have been over 270 species of birds recorded on Tiree, among them 6,000 pairs of waders. Offshore, orcas and basking sharks can be seen in the summer months while inshore, otter and seal populations flourish.

In the late sixth century, St Columba established the first Christian monastery on the island. In the eighth to ninth centuries, marauding Norse raiders turned peaceful settlers, naming the island Tyrvist, the Land of Barley, from which it gets its name today. The population grew steadily to almost 4,500 by the mid-nineteenth century, but Tiree was not exempt from the potato famine and many families emigrated to Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Patagonia. Today the population is around 650, although it is estimated that there are over two million people of Tiree descent in the world today.

To mark the new millennium, An Turas (the journey) was built at Gott pier. This open structure leading to a covered aperture is designed to represent various aspects of the island, from its vernacular architecture and heritage to the geology and landscape.

On the north coast, near Balephetrish, stands the Ringing Stone (Clach a’Choire), a boulder carved with Neolithic cup-markings. The stone is a glacial erratic, carried to Tiree from Rùm during the last ice age. Folklore, however, says that a giant threw the stone across the water from Mull and should it ever be broken, or taken from Tiree, then the island will be lost to the waves.

All images and words © Elementum Journal.

Elementum is a collectable coffee-table journal that explores our connection to the natural world. It is for the curious and questioning, for lovers of art and story, for those as open to understanding the world told through ancient myth as explained through scientific research. Guided by a different theme for each edition, Elementum is published twice a year.

If you enjoy reading about the natural world and its associated folklore, appreciate exquisite artwork, informed writing, clean design, and highest quality print then Elementum is a perfect new addition to your library.

Editions One and Two of Elementum: A Journal of Nature and Story are out now priced £15.00.

Dòmhnall Meek/Donald Meek, is a renowned writer, lecturer, broadcaster and a leading expert of Celtic and Gaelic studies, who hails from the small Hebridean island of Tiree. This new poetry collection touches upon a variety of subjects, including his homeland of Tiree throughout the years, the Highlands, friendship and the world we live in today. These themes are showcased in these three extracted poems.

Extract from Sreathan anns a’ Ghainmhich

By Dòmhnall Eachann Meek

Published by Acair

Iomradh Toisich

Leis mar a tha Tiriodh air atharrachadh rè mo bheatha-sa, tha e duilich dhomh an-diugh a chreidsinn gun deachaidh mo thogail anns a’ Chaolas aig ceann an ear an eilein, ri taobh Sruth Ghunna, ann an dachaigh far an cluinninn a’ Ghàidhlig moch is anmoch. Bha am baile air an aon dòigh.

Bha an taigh againne, ‘Coll View’, na nead de ghinealaichean, ’s na ginealaichean sin a’ sìneadh air ais gu 1870. Bha m’ athair na chroitear agus na mhinistear, agus thill e fhèin agus mo mhàthair do Thiriodh à Ile ann an 1949 a fhrithealadh air dlùth-chairdean a bha a’ faireachdainn uireasbhaidhean na h-aoise. Thogadh mise còmhla ris na seann daoine sin, daoine a bha òg is sùnndach nan spiorad, ’s iad luma làn sgeulachdan is òran.

Bha cuid aca ri rannan, m’ athair nam measg, ’s e ag amas mar a bu trice air coin is cait seach daoine. Bha am baile làn de dh’ òrain cuideachd, agus spèis shònraichte ga toirt do bhàrdachd. Os cionn gach neach, bha a’ choimhearsnachd a’ toirt urram do dh’ Iain mac Ailein, ‘Bàrd Thighearna Cholla’, a rugadh sa bhaile, agus a chaidh do dh’ Albainn Nuaidh ann an 1819.

Cha b’ ann gu h-aotrom a chleachdte am facal ‘bàrdachd’ a bharrachd. Bha a’ mhòr-chuid ‘ri rannan’, ach cha robh iad ‘ri bàrdachd’. B’ e gnothach àrd, uasal a bha an sin. Ged a dhèanadh neach òran, cha robh sin a’ ciallachadh gur h-e ‘bàrd’ a bh’ ann.

–

Tha mi mothachail nach e ‘bàrd’ a tha annamsa a tha airidh air àite am measg nan urramach a chaidh romham no a tha ann an-dràsda. Gu math tric, tha na h-annasan a tha mi a’ tairgsinn nas fhaisge air dealbhan-camara, air daoine is air àiteannan, a tha a’ tighinn thugam ann am facail tro shùil na h-inntinn. Tha na modhan a tha mi a’ cleachdadh a’ siabadh a-nùll ’s a-nall eadar na ‘strophics’ agus na h-òrain, eadar na dàin a tha teann nan cruth agus na ‘rannan’ a tha fosgailte. Mar eileanach, tha mi tric a’ dol gu muir nam smuaintean, agus tha samhladh a’ bhàta is gnothaichean na mara agus a’ chladaich a’ nochdadh gu minig.

Agus, mar fhear a tha cho faisg air a’ chladach, tha fhios agam nach eil anns na rannan seo ach rudan aimsireil nach mair – sreathan anns a’ ghainmhich, a dh’fhalbhas le muir-làn nan linntean, mar a dh’fhalbhas mi fhìn, agus mar a dh’fhalbh na daoine air a bheil mi a’ cuimhneachadh anns na marbhrannan anns an leabhar seo. Fhad ’s a mhaireas iad, ged tha, tha mi an dòchas gun toir na sreathan seo smuaint air cuideigin.

Iain Againn Fhìn

Aig Arras cha robh do smuaintean

Air poll no eabar no uamhas,

Air gunnachan mòra le nuallan

A’ tilgeil shligean gun truas annt’,

A’ treabhadh talamh torrach na uaighean,

No air cuirp a’ grodadh sa bhuachair,

Gun sealladh air latha na buadha;

B’ e do dhleasdanas bu dual duit,

’S thill thu bho thaobh thall nan cuantan

Gu feachd Earra Ghàidheal ’s nan Sutharlan;

Tìr nam beann ’s nam breacan uallach

Ann an èiginn – ‘Dìon do dhualchas!’

Ach bha do smuaint sa mhionaid uaire

Air obair earraich san eilean uaine,

Teaghlach a’ cosnadh lòn le cruadal,

’S do mhiann a bhith le crann a’ gluasad,

A’ gearradh sgrìob gu treun tron chrualach,

A’ cur an t-sìl le dòchas buannachd

Fa chomhair nan geamhraidhean fuara.

Bheuc an gunna mòr gu suaicheant’,

Sanas-maidne blàr na buadha,

’S leum thu, Iain, far na bruaiche,

Toirt taic dod chomanndair uasal;

Am peilear guineach, beag cha chual’ thu,

Tighinn le fead ’s do dhàn san luaidh’ aig’,

Bho fhear-cuims’ bha falaicht’ bhuatsa;

Thuit thu le lot nach gabhadh fuasgladh;

Geamhradh na fala a’ toirt buaidh ort.

‘Iain Againn Fhin’, bu truagh e,

Sìnte anns a’ bhàs neo-bhuadhmhor,

’S na ceudan ghaisgeach marbh ra ghualainn –

Earrach searbh an Arras uaignidh.

Geamhradh Dhòmhnaill 2014-15

Siud mar chuir mi ’n geamhradh tharam

Ann an Tiriodh ’s stoirm gach latha:

Siud mar chuir mi ’n geamhradh tharam.

Falbh le coinnlean anns a’ mhadainn

Leis a’ mhilleadh rinn tein’-adhair,

Sporghail feuch am faighinn maidse,

Ged nach dèanadh aon dhiubh sradag.

Chaidh mi cuairt a-nùll am machair

Feuch am faicinn sgeul air aiseag,

Ach cha d’fhàg an ‘Clansman’ caladh –

Anns an Òban fad seachd latha.

Cha seasainn cas le neart na gaillinn,

Mo chorp ga lathadh aig na frasan,

Air mo bhogadh chun a’ chraicinn,

’S na coin air iteig anns an adhar.

Cha robh tunnag anns a’ bhaile,

Cha robh coileach, cha robh cearc ann:

Sgeul gu bràth orra chan fhacas –

Gus do land iad ann am Barra.

Na bionaichean a’ leum gu bragail,

A’ dannsa am fan-dango snasail,

Tilgeil sgudail feadh an achaidh,

’S iad a’ tarraing teann air Canna.

An aon bhùth san eilean falamh,

’S mi gam tholladh aig an acras:

Cha robh feòil ann, cha robh aran,

No ‘biadh deiseil’ anns a’ phlastaig.

Cuirm-chiùil am broinn an taighe

Is na h-oiteagan ga shadadh:

O, nan cuala sibhs’ am blastadh

Is an ùpraid bh’ aig gach maide!

Sin mo sgeul, a chàirdean gasda,

’S cha bu mhath gum biodh i agaibhs’ –

Chuir an geamhradh mise thairis,

’S dh’fhàg e mi gun neart ga aithris!

Sreathan anns a’ Ghainmhich by Dòmhnall Eachann Meek is out now published by Acair priced £11.99.

Marilyn Brown argues that far from being separate from societal developments, gardens in Scotland are, and always have been, inextricably linked to aesthetic, social, technological, economic and political attitudes. Tracing the Scottish garden to a wider European movement, this extract gives insight into some stellar examples in Iona, Glasgow, Angus and elsewhere.

Extract from Scotland’s Lost Gardens: From the Garden of Eden to the Stewart Palaces

By Marilyn Brown

Published by Historic Environment Scotland

The garden and its companion, the designed landscape, are important elements in the cultural history of Scotland. They also form one of its more ephemeral elements; subject to constant variation on a small scale, they are, on a larger scale, relatively easily changed or abandoned, leaving little or no trace. The creation of gardens, and the form of garden adopted, provides insights into the culture and philosophy of the society that designed and produced them. Like any other art form the style of a garden mirrors the aesthetic, social, technological, economic and political attitudes of the time. More than this, they intimately reflect the personality and ideals of the individuals who created them, and chart the changing fortunes and ambitions of successive generations. Through its gardens Scotland may be seen as part of a wider European movement, drawing on the same literary and visual influences and sharing a common medieval, renaissance and early modern heritage.

© HES

The first gardens usually discussed in Scotland are those of the monastic communities, which colonised the west of Scotland , and the islands of the Hebrides in particular, from abbeys in Ireland. Iona, the most prominent of these, was founded by St Columba about 563. This aerial view of Iona Abbey shows the remains of the monastic vallum or boundary bank around monastery. There are indications of organised enclosures within the vallum, serving different functions for the running of the community.

© HES

Herb gardens were not restricted to monastic houses. The University of Glasgow, founded on the High Street in 1451, had various gardens – a little meadow, an Old Pedagogy Yard, Paradise Yards, West Yards and a great orchard. The Old Pedagogy was for growing vegetables and for supplying fowls for the kitchen and common table. There was a small physic garden nearby. This engraving by John Slezer shows the university’s orchards and gardens as they appeared in late seventeenth century.

© HES

Like the dignitaries of the Church, the kings of Scotland were linked to their peers elsewhere in Western Europe. This common cultural background applied to the creation of their gardens, as much as to their choice of music, literature or chivalric display, and gardening in Scotland in the medieval period can be seen as forming a part of a wider European practice. Holyrood was an occasional royal lodging throughout this time, with the abbey employed for major ceremonies and the adjacent park for hunting. One of the earliest references to a garden there is from 1506, when James IV gave five shillings to a Queen of May as he walked to the garden of the abbot.

© HES

The most obvious change to Scottish society in the later sixteenth century was the establishment of the reformed Church as the official religion of Scotland. Gardens in Scotland illustrated both change and continuity; the fashion for the enclosed garden survives, but grows in size. While food production to support the household remained central, the relationship to the castle or country house becomes more explicit, with the garden arranged to complement the building. Although designs with a direct axial relationship between the two may belong to the following century, Castle Campbell shows recognition of this form of presentation, which may also have a practical, protective function. The house and the garden express their owners’ changing perception of their country and society and their place in it.

© HES

The year 1603 saw a major change in the social fabric of Scotland with the departure of the king and court to England. The best known garden of this period is probably that at Edzell Castle in Angus, property of the Lindsay family. This is the most well preserved of the surviving gardens of the early seventeenth century, and provides, through its sculpture, evidence for the elaborate intellectual framework which lay behind its design, and may have extended to the choice of plants.

© HES

After the peaceful return of Charles II as king, Scotland, which had endured much disruption as the consequence of the battles of the civil wars on its territory, appeared to resume the pattern of social life of the earlier part of the century. The dominance of the landed gentry in this period was epitomised by the construction of country houses and their gardens. Leslie House with its well-preserved terraced gardens was built in the late 1660s. It belonged to the Duke of Rothes, and was one of the first houses and gardens to be constructed after the Restoration.

© HES

A cursory examination of the Roy Military Survey, the map prepared between 1747 and 1755 in the aftermath of the 1745 Jacobite rebellion, reveals a country studded with formal gardens and landscapes that stand out against a background of agricultural use. Many of these estates had been newly laid out in the first half of the eighteenth century, and indicate the continuing adoption and desirability of the formal plan. At Drumlanrig Castle, there has been a partial reconstruction of these formal gardens of the early eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Scotland’s Lost Gardens by Marilyn Brown is out now published by Historic Environment Scotland priced £20. All photographs in the above excerpt are taken from the book.

You can see more images from the book here on Books from Scotland.

This month David Robinson examines acclaimed poet Polly Clark’s debut novel Larchfield. The dual narrative follows W H Auden and Dora Fielding who arrive in Helensburgh decades apart, but are united in their struggle to assimilate within the quietly sinister echelons of polite society. A gripping and ambitious take on the interplay between isolation, creativity, and self-destruction, David also finds Larchfield valuable in highlighting a lesser-known period in W H Auden’s life.

David Robinson Reviews: Larchfield

By Polly Clark

Published by riverrun

I saw Auden once. He had only months to live and was sitting in an Oxford café looking out of the window with a bored expression; I was on my way to an interview at a college around the corner, an 18-year-old bundle of nerves and expectations. That’s all it was: a wordless glance through a café window before he went back to his coffee and newspaper. Though fictional, the Auden that Polly Clark gives us in her wonderful debut novel Larchfield, is far more vividly realistic than my own briefest of brief encounters with him.

The Auden it introduces us to is not much older than I was back then; it’s 1930, he has finished Oxford, and has just taken a teaching job at Larchfield, a prep school in Helensburgh. And though we are taken completely into his life in this repressive, bourgeois redoubt – “the Wimbledon of the north” according to Cecil Day-Lewis, his friend and predecessor at the school – we only enter it through the mind of another poet. Dora Fielding – also English, also from Oxford, also isolated – has moved there nearly 80 years later, and the point about Dora’s mind is that she fears that she is losing it. Post-natal depression and neighbours from hell are pushing her further towards the brink. Finding out more about Wystan seems to be the only thing that can save her.

So we follow him into the closed, cruel worlds of the boarding school and Helensburgh polite society (“You seem awfully nice in person” Wystan is told at one party, “and I’m sure your next book will be much better”). There are moments of escape, and we follow him there too – to brief holidays with his Christopher Isherwood where he makes the most of the soon-to-vanish freedom of Berlin’s gay clubs, and into a love affair with a working-class lad back in Scotland. And, of course, into poetry, although not quite as much as you would think considering that this is a book about two poets and written by a poet as well (Clark has three collections of poetry to her name and has been shortlisted for the TS Eliot Prize).

So we follow him into the closed, cruel worlds of the boarding school and Helensburgh polite society (“You seem awfully nice in person” Wystan is told at one party, “and I’m sure your next book will be much better”). There are moments of escape, and we follow him there too – to brief holidays with his Christopher Isherwood where he makes the most of the soon-to-vanish freedom of Berlin’s gay clubs, and into a love affair with a working-class lad back in Scotland. And, of course, into poetry, although not quite as much as you would think considering that this is a book about two poets and written by a poet as well (Clark has three collections of poetry to her name and has been shortlisted for the TS Eliot Prize).

The story-telling is layered, clever, captivating. But half-way through, Clark takes a huge risk with her parallel plots. She merges them. Dora wanders into Wystan’s world and the novel starts performing its magic. There’s the sheer wonder of turning back time when those worlds join; when they threaten to split, you can almost feel the cold wind of reality rushing in again, like those scenes in films (and possibly real life: you tell me) when people who are drunk or on drugs are suddenly drawn back into stone-cold sobering reality.

The meeting between Dora and Wystan is such a dazzlingly high-wire act that I needed to check with Clark whether mentioning it would be a spoiler. “Not at all,” she says. “It’s a massive part of the book. And it needs to be real so the reader would wonder whether Dora actually met Wystan. The tension in the story is whether or not she stays in his world.”

Clark is the literature director of Cove Park, a writer’s retreat near Helensburgh, where she has lived for the last four years, as well as in the surrounding area for a further seven. Ever since she arrived – like Dora and Auden, from Oxford, where she had worked for a publisher – she had known about Helensburgh’s Auden connection, that the poet had taught at Larchfield for a couple of years and that his first major collection, The Orators, was written while he taught there. Her daughter is a pupil at Lomond School, which is on the site of Larchfield. “Although the building in which Auden lived while he was there has been converted to flats, the façade is exactly the same, and in the photographs I’ve got of him with the boys, the background hasn’t changed. Helensburgh hasn’t altered too much either. I really didn’t need that much imagination.”

“This was such a formative time in his life,” she says, “yet nobody has really written about him in Helensburgh. But I didn’t want to write a biography, so for years I didn’t have any kind of hook on which to hang my knowledge of him. I used to wish it had been a completely different poet, someone I could relate to more – like Ted Hughes, say – because I didn’t think I had anything in common with Auden. He’s posh, he’s gay, I didn’t like his work so much – though I do now. I just didn’t see any connection.”

“Then I realised we had everything in common. We were both outsiders. Neither of us could be ourselves any more, we were both hiding who we are.” Or, as she explains on the proof (though not the finished) copy of the novel: “I seemed to ignite anti-English feeling wherever I went. I couldn’t drive and became very isolated. When I had a baby, my ruin was complete. That’s when I first read Auden’s The Orators. And its poems changed my life.”

They are, I mention, fairly impenetrable too. “It’s a bonkers book,” she agrees. “But if you are living in Helensburgh and in some sort of extreme state, it makes absolute sense. When I read it, I thought ‘This is somebody who is absolutely repressed, trying to talk about things they can’t talk about, and all their brilliance is squeezing out in all these funny directions.’ But there are Helensburgh landmarks all over in it – Loch Long, the ferry, the railway station – and when I came across them, the poems seemed to explode in my mind. And I just knew that if I had met Auden we would have been friends.”

We are, I feel, getting to the core of why Larchfield works so well. Although Clark downplays the importance of any anti-Englishness both Dora and Auden encountered, she can clearly imagine it, along with antagonistic neighbours (nothing to do with real life, she insists) exacerbating the worries she clearly felt ten years ago as the mother of a premature baby daughter. “Dora isn’t me, but certainly it’s easy to imagine young mothers going off their rockers at such a time, when your whole sense of who you are is completely obliterated. I took things a lot further than my own experience of new motherhood. With her, I could let the madness leak out.”

And so the madness leaks, time spills, and readers no longer know for certain which decade they are actually in, only that everything is impeccably drawn, far more believable than it ought to be. To me, it’s like being able to go into an Oxford café, decades later, and sit opposite a bored-looking genius poet, and know – if not quite everything about him – at least enough to know the answers to many of my questions. No-one else, I reckon, could have written such a fine novel about Auden’s time in Helensburgh. And after Larchfield, I don’t think anyone else will even dare to try.

Larchfield by Polly Clark is published on 23 March by riverrun priced £14.99.

This article by author Louise Greig passionately addresses the influence of nature on her work. In particular Louise considers how the natural world directly shaped her forthcoming children’s book, The Island And The Bear, set in the Hebrides. She also argues that engaging with nature – both through reading and outdoor exploration – is fundamental for developing children’s understanding of the world and their place in it.

Writing About Nature Through Verse

By Louise Greig

I am in love with nature! As a child my bedroom was a health and safety nightmare with a menagerie of animals living under, on and in my bed. Animals were my whole world. Later on, in adulthood, I took to the hills at every opportunity, immersing myself in the rugged landscape of the Cairngorms so evocatively captured in the writings of local writer, Nan Shepherd (author of books including The Living Mountain – you can read an extract here).

Poetry and books were my world too. Nature and poetry go hand in hand. Poetry holds a candle up to the things that matter; it lets us examine them more closely and connect with them on an emotional level and come away changed. We are part of nature and it is impossible to separate ourselves from it.

Spread from The Island And The Bear

Nature writing for children comes from the writer’s love and perception of nature and requires a translation of that experience into a language that allows a child to develop an empathy and affinity with the natural world. For young people I believe this is more important than ever. Increasing urbanisation and declining freedom for children to explore the great outdoors for themselves has resulted in generations of people increasingly insulated from both the beauty and harsh realities of nature. At a time when environmental issues are key to our future it is critical for young people to develop a balanced perspective of the world and their place in it. It also provides much needed emotional balance. Books are a beautiful way to spark a love and curiosity for the natural world in a child’s formative years.

I have enjoyed a lifelong, deeply poetic relationship with nature. Life is rhythm. Nature is rhythm. Poetry is rhythm. A good poem has a heartbeat. Verse is a way of telling a story in a beautiful rhythmic way and lends itself perfectly to being read aloud to a small child.

Spread from The Island And The Bear

The Island and the Bear is a picture book I have written for young children set on a small Hebridean island. The wild beauty of the island and the incongruous arrival of the gentle bear seemed to ask for the story to be written in a poetic way. Verse, along with Vanya Nastanlieva’s strikingly beautiful illustrations, gently pulls us along behind the bear until we gradually come to understand him, and perhaps by doing so, understand ourselves a little better.

Written in free verse means that it has rhythm and rhyme but is less rigid in form than strictly metric verse. Island life perhaps more than anywhere is attuned to nature’s rhythms. A small island cannot escape the constant presence of the sea, wind and weather: “The bear tilted his ear to the drum of the wind and the surge of the sea”. Free verse seems a perfect fit for this story – it allows the bear to ramble a little, in keeping with his wildness, whilst keeping a loose rein on him! Through the rhythm of free verse perhaps the bear’s heartbeat thumps just that bit louder. And if he makes friends with a few small children out in the world then that will be the most poetic and beautiful thing of all.

Louise Greig is a poet and author born in Scotland. She has won several writing prizes, including the Manchester Writing for Children Competition and the Wigtown Poetry Prize. She is inspired by the Scottish landscape, and the company of animals. She lives in Aberdeen with her rescue greyhound, Smoky. She is the author of The Island and the Bear, to be published on 16 March, by Floris Books under the Picture Kelpies imprint.

Author Jenni Daiches does not describe herself as a ‘nature writer’. Yet as she reveals here, nature and her response to the Scottish landscape have profoundly pervaded her writing, most recently in her new novel Borrowed Time which takes place somewhere – the location is purposefully left unnamed – in Argyll.

Nature, Naturally

By Jenni Daiches

I am not a nature writer, but the natural world is part of the environment in which I live, so of course I write about it. When ideas for my novel Borrowed Time began to take shape, I did not specifically plan to write about the natural environment in which much of it takes place, but it was there, part of my central character’s experience.

Sonia visits the Highlands in the aftermath of her husband’s death, following what seems a tenuous thread linking her to her mother’s Highland ancestry. Happenstance takes her to a small Highland town where she stumbles on a dilapidated railway carriage up for sale. On impulse, she buys it, and transplants herself to a solitary existence in territory totally new to her. She walks in the woods and climbs Mid-Argyll’s small hills. She notices butterflies and the tracks of deer. She watches the chaffinches that cluster at her doorstep and the ducks puttering on the canal. On a clear day, she can see Cruachan, which her mountain-loving son climbed, and she makes a pilgrimage to An Teallach, for her a memorial to her son. She tames her wild garden and takes pleasure in growing things.

I don’t name the place of Sonia’s railway carriage, though anyone familiar with that part of Argyll will surely be able to identify it. Naming a narrative’s location – unless it’s a fictional location – is a kind of cipher. Even if your readers don’t bring to the page their own conceptions of Glasgow or Edinburgh or Aberfeldy or Banff, the naming of them signals a particular location. Without a name, you have to create that particularity; I could not have created Sonia’s world if I had ignored the impact of its natural features.

Borrowed Time is structured over nine months of the year 2014, with flashbacks telling the story of Sonia’s past life. It begins in January, and the changing seasons are part of the rhythm of the narrative. In April Sonia sits with her dogs on the grassy edge of a small loch: ‘the cloud is breaking to reveal tentative blue… There are primroses out, and celandines, and pale green buds on the birch trees.’ Near it is an abandoned croft ‘rising out of a tangle of nettles and brambles. The stone is furred with moss.’ There is very little of Scotland’s landscape that is not imprinted by human activity. When Sonia gazes at An Teallach she sees a mountain that ‘seems astonishingly new, as if its wildness was freshly minted for my eyes, but I knew it was old and savage’. She feels threatened by the mountain’s jagged outline, but the path she walks on has been created by humanity and there are fresh boot prints to prove it. A mountain path, crumbling walls, nettles, all tell of human habitation. Most wilderness reflects human activity, if it is not actually human-made.

The book ends on 18 September, when Sonia on her seventieth birthday walks along the canal bank into the little town to vote in the independence referendum. ‘The leaves are turning and the water is a deep brown freckled with their bronze and gold. I spot a heron on the far bank, predatory and preternaturally still.’ Is there an echo of the political climate in the colours, the stillness, the sharp-eyed hunter, the turning of the year? Sometimes these resonances happen of their own accord.

I have been asked about the origins of my response to the Scottish landscape. Perhaps it goes back to my Highland grandfather, born near Glenlivet, and my grandmother from an Aberdeenshire farming family, although I knew neither of them. Or childhood holidays. Or holidays from Galloway to Orkney with my own children. It has certainly been nourished by much exploration since and over the last 25 years by all the time I have spent at my partner’s house on Lochfyneside. (And yes, sharp-eyed readers will notice the connection with Borrowed Time.) But there is so much yet to discover, so much of Scotland to be walked and observed and felt. There are so many more stories to be told, which will inevitably involve a world where mountains loom and trees grow and birds sing.

I live beside the Firth of Forth. I walk everyday with my dog along a path that was once a railway and today, a cold bright February morning, is alive with wrens and blackbirds and rabbits and squirrels. The trees are in bud and crocuses and daffodils are out. Tame perhaps, but the firth itself and its history, its three great bridges magnificent in the sun, symbolise everything one might want to say about humanity and nature. How can one not write about the natural world, if only to demonstrate the consequences of human activity?

Borrowed Time by Jenni Daiches is out now published by Vagabond Voices priced £11.95.

Legendary climber and award-winning author Hamish Brown reflects on his childhood explorations including a pilgrimage to ‘Snowdrop Valley’ – ‘a very special secret place’ – where the delicate bloom of the pale flowers marked the beginning of spring in the Ochils.

Extract from Walking The Song

By Hamish Brown

Published by Sandstone Press

The Lure of Snowdrops

My home territory as a boy was the Ochils and the whole landscape enclosed by the encircling River Devon – an anglicisation of what Burns should have called Dowan in one of his poems. Its course in the hills has improved with the maturing of reservoirs and woodlands. The ‘crook’ in the river is a classic example of ‘river capture’ as, originally, it flowed into Loch Leven. Below the gorge with the bridge on top of bridge it pours over the Cauldron Linn. One of the area’s Victorian country mansions tapped this force to make its own electricity, an energy source which has been recreated today. My western bounds of the Devon were really the Dead Waters: fields which were flooded in winter from the river to allow skating. In my youth the school had official half-holidays for when conditions were right and town and gown would flock to the site to enjoy the ‘Skating Halves’. This is a forgotten joy today, such freezing a thing of the past. (Climate change? Global warming?)

One of my lifetime hobbies of ‘rescuing’ trees began on the River Devon. A riverbank rowan had seeded onto a mossy rock and grown into a fine small tree but its weight then toppled it from its scant hold on the rock and the victim lay thrashing in the flow, only held by a few roots. I took the tree home and planted it in our garden. It’s still there, saluted every time I drive past. (When you visit Sourlies bothy or Shenaval – greet my rowans there please.)

Facing where this tree once grew is a den (dell) which was, long ago, laid out with paths from a mansion above. One path led to the Cauldron Linn, but all the paths were overgrown and the den itself almost impenetrable – which was an additional attraction for the roaming schoolboy. The roof had already been taken off the mansion when I discovered the den sometime soon after WW2. The banks below the ruin into the dell were an amazing spread of snowdrops, ‘millions of them’ as I reported once home and then dragged mother to ‘come and see’. We took some home and they still thrive, as snowdrops do, lining the path up to the front door. We called the place Snowdrop Valley and shared its location with very few other people. It was a very special secret place.

Nosing about the half-ruined mansion at the end of one snowdrop season I found a very puzzling flower. The flower itself was rather like a snowdrop but the leaves were like big daffodil leaves, while the bulb was more like that of a hyacinth. Baffled, I took one round the village to show it to anyone who might recognise the flower. Nobody did. I was even accused on one occasion of creating a leg-pull. In despair I sent it to the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh. They replied that it was a Summer Snowflake, Leucoium aestivum, which was once popular in Victorian gardens but had dropped out of favour. There is a smaller Spring Snowflake as well, Leucoium vernum and both are enjoying a renewed popularity sixty years on from my discovery.

But it was the snowdrops that became my passion and every spring I’d make a pilgrimage to Snowdrop Valley to see the spectacle. There’s nothing like a woodland alight with snowdrops to make the heart lift. There is a folk story about snowdrops. When Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden they found a world of winter desolation. Seeing Eve weeping in the snow an angel started breathing on the falling flakes so on touching the ground they became the flowers we know, ones to symbolise returning warmth and hope for the world. There is a touch of immortality about snowdrops, the way they come each year (some through tarmac in my garden!) and spread and multiply, without any need of us. Their only enemy – but also good friend – is man. Creating snowdrop woods became another lifetime hobby.

On another schoolboy visit to Snowdrop Valley I received a shock. The mansion house had been demolished and the rubble bulldozed down onto the snowdrop bank. The snowdrops were buried. I was so upset I did not go back there for about twenty years; when I did it was to receive another shock: the bank was as white as ever with snowdrops.

Investigation revealed why. The buried snowdrops had grown, and even put up white-tipped spears of flower – underground – then, instead of the plant’s goodness going down into the bulb, another bulb was created an inch or so up the stem. Year by year they had fought back determinedly to reach the surface. A snowdrop miracle, take what symbolism you will from it.

Walking The Song by Hamish Brown is published on 16 March by Sandstone Press priced £8.99.

For bestselling author Jane Yeadon, growing up on a farm in the north of Scotland could be both rewarding and challenging. In this nostalgic and evocative excerpt Jane recounts days spent shivering while playing ‘circus’ in the cattle-feed barn, awaiting the painfully slow onset of Highland springtime alongside Frankie the bull, Dobbin the horse, and Pansy the cat.

Extract from Telling Tales: Growing Up On A Highland Farm

By Jane Yeadon

Published by Black & White Publishing

Spring should be well on its way but winter’s returned, sending a wind with icicles in its breath to bother the barn’s roof slates. They rattle in protest but, heedless, it blasts beneath one door, making a chilly tunnel through to the opposite one leading to the steading. It’s the same route Mum took on her way to sorting out Frankie but I’m staying here. I’m keeping away from the draught on the stairs leading up to the grain loft.

It’s full of calf-feed sacks. As I sit dreaming of the future, a whiff of linseed escapes through the bags’ hessian. It wafts past with the same odd pungency of the sawdust at the circus where Granny once took us.

Looking round, everything suddenly becomes so crystal clear that it merits jumping up and dusting my hands on my kilt. It’s a piece of luck that we’ve got this barn. Why didn’t I think of it before? It’s got loads of space: ideal for practising. What could be more exciting than life in a circus?

When I grow up, I’ll join one.

As a starting point: something simple. Remembering the ease of the trapeze artists flying through the air, I check the rafters. They’ll be perfect for swinging on, and if I jump high enough, easy to reach from the top of the stairs. The barn’s stone floor might have its drawbacks and even from this vantage point does seem far down below. Still, it’s mostly covered in a high pile of loose straw. It’s not quite a safety net but it’ll do.

Occasionally on a dark night at home shooting stars rain silver showers on our dimmed moor with the same magical ease that the circus artists gave to their act. As they flew, twirled and pirouetted from one trapeze bat to another, the sequins on their scanty satin costumes sparkled in glittering arcs under the spotlight. Who could imagine so many of these bright discs could be fitted onto so little a space? One day I’ll get to wear one of those costumes, then, starburst-like, will fly through the air to the rapturous applause of a huge audience.

It’s an inspiring dream. Of course everybody has to start in a simple way but the experience of being brought up on a farm with a wild bull should guarantee quick promotion in the circus world. Look at Frankie! Have I not managed to survive living alongside this awesome animal?

As if mind-reading, he lets out a high-pitched shriek. It cuts through the barn’s thick walls with as vicious a sound as that of logs being sliced on our circular saw. The combination of the roar of the tractor that drives the belt and wood being cut makes such an endless racket that I should be grateful that Frankie’s cry is brief.

Still, I shout, ‘Awa’ an’ bile yer heid, Frankie. I ken you’re mad cos you’re shut in, but it’s for your own good. Instead of making that horrible racket you should be glad you’re inside. It’s miserable outside. Just listen to that wind!’

I’ve never been close enough to stare back into our bull’s red-hot eyes but they appear too often in my nightmares. Today, however, he’s not grazing in some field you might have thought was empty and so get a fright to see him there. We’re safe enough because Dod’s properly fixed the hole in the wall that Frankie made.

Still I remember the warning. ‘Dinna go near that beast. Nay animal likes to be shut in, especially Frankie. He’s right enough outside but, to tell you the truth, when he’s penned in and I’m feeding him I feel the better o’ having a pitchfork wi’ me . . . just in case. Of course, your mother,’ his voice softens as he continues, ‘she says that all he needs to keep him in order’s a good row, but that’s your mother.’ He shakes his head in admiration. ‘Aye, she’s a bit of a control merchant, right enough.’

A pitchfork together with Mum’s method of managing Frankie seems a good combination. It would probably work on caged circus animals too. I remember the penned-in lions. They sounded like lots of trapped bulls on a bad-weather day but I also recall them slinking into the ring, looking more sad than angry.

And it did seem a bit daft getting them to sit on seats far too small for them. The trainer’s free use of a whip to help them get the idea meant they did as they were told but it looked cruel to me. It was probably just as well that Granny had nodded off at this point in the show and that Mum wasn’t there. What’s the betting she’d have been shouting advice at the trainer? I nearly did it myself but, just as I opened my mouth, Elizabeth shut me up with one of her dark looks and an elbow jab.

The black stallion was far happier. For his performance, he held his plumed head high as he galloped round and round the ring, his coat gleaming, tail streaming and mane flowing. It was easy to see that he was proud carrying his bareback rider. She didn’t need a whip. Instead, before standing up to wave to us, she whispered to him, gentling his neck. The sound of his hooves thumping on the sawdust added so much excitement that we all got to our feet to cheer at the end of the performance. Perhaps the horse enjoyed it too. He bowed his head right down to the ground, as his rider acknowledged the applause.

‘And I’ve got a horse too! I’ve got you,’ I call to Dobbin, patiently waiting at the bottom of the stairs. His head’s back on. It surfaced in Duck’s house under the fir branches. I had forgotten it was left there. Dobbin looked so much better when returned to his other half. He was also long-suffering when I tried to fix it on for good.

‘I’m afraid bits of wood’s not the answer,’ I’d to tell him, ‘but I’m sure if I get some Copydex glue that’ll do the trick. Let’s have another go tomorrow. Mum says it sorts everything out. Only I need to get it from her first. She says it needs to be rationed out. The last time I had it, it went everywhere.’

I hadn’t reckoned on Dod’s joinery skills.

‘When you were in bed last night, I nailed your horse’s head back on.’ He sounded so pleased it didn’t seem right to say that it would have been nice to have helped. Dobbin’s my horse so it would have proved to him that he’s got a caring owner. I’d have had a shot of the good stuff in Dod’s toolbox as well.