Shreela Flather cogently argues that women must be central to every initiative, business project and political goal rather than being merely after-thoughts or decoration. For Shreela, it is all about income generation, and her book calls on international businesses to improve efficiency and profitability through the greater employment of women.

Extract from Woman: Acceptable Exploitation for Profit

By Shreela Flather

Published by Whittles

Introduction

My proposition is based on sex and profits. This is not a book about Women’s Lib, but it is a book which will lead to the recognition of women carried along by the wholehearted support of men; it is not another call for charitable donations, but it is a book about investment.

The poorest women of the Indian sub-continent and Africa represent a vast untapped resource and are easy to find. They are hard-working and eager to learn – the perfect workforce. But today they have no sense of self-worth; they murder their own baby daughters because they are deemed to be of no value, indeed harbingers of debt; too often they are regarded as little more than beasts of burden, or they are hidden away, deprived of education and position.

I want to turn these countless millions of wives, mothers and daughters into profit generators for themselves and for the global business community. I will tread on a few toes along the way, tackle the great taboo of children working for a living and face up to arguments against managing an ever-increasing population using birth control. You can’t talk about the role of women in isolation from their sex lives.

I will challenge politicians to turn talking shops into practical action; the much vaunted United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) dream cannot be fulfilled by the target date of 2015. Its only hope is to shift the focus to women. While the UN rightly identifies the private sector as the ‘engine of innovation and growth’, it fails by not targeting that effort at women directly. As part and parcel of that refocusing, it should start talking about family planning.

Author Shreela Flather

Women must be central to every initiative, business project and political goal, rather than afterthoughts or decoration. And, dare I say, this is just as applicable to the West, and the UK in particular, where the Equality and Human Rights Commission reported in September 2008 that the number of women in top jobs was actually falling; far from breaking through the glass ceiling, women have crashed into impenetrable triple-glazing. So let no one say that the case for women’s rights anywhere in the world has been addressed fully, let alone met. When we stop saying with surprise that the head of some corporation or organisation is a woman, then I will feel satisfied.

I am convinced that if the male mindset can be changed then the women will take care of the rest. The result will be profit for business, income and welfare for poor families, rescue for the environment and votes for politicians. The arrogance is not in maintaining that any single idea can bring about a change: rather it is in believing that the status quo can continue. As we slide ever deeper into global economic depression, this above all is a hopeful book offering a practical, affordable way forward. It requires no new energy source, it demands no vast capital investment and it will have no destructive impact on the environment. The workforce is vast, willing and able. A mother will not squander her money; she will nourish her children rather than drinking herself into oblivion, and she will remain loyal to her family.

This is not about charity. It is not about improving the education of women. It is all about income generation. Woman: Acceptable Exploitation for Profit is a solution for a world in trouble, a roadmap to greater opportunities, profit, prosperity, health and happiness for all, regardless of gender. And before this notion is dismissed as fanciful wishful thinking, critics should first consider some of the examples where a handful of enlightened business leaders are already reaping the rewards, just as their new female workforce is transforming their own lives and those of their families and villages.

This is not pie-in-the-sky: it is happening, but so far this practical and demonstrably successful concept has not received the recognition it deserves. We live in a world struggling to feed itself, fund itself, preserve itself, so why reject an asset and talent we have failed to consider?

Woman: Acceptable Exploitation for Profit by Shreela Flather is out now published by Whittles priced £16.99.

The late influential social reformer, peace activist, and policy advisor Kay Carmichael muses upon life and death in the new book It Takes a Lifetime to Become Yourself. Here she finds a connection between a young woman in Glasgow and an exhibition of artist Francis Bacon, and recalls a Women for Peace demonstration.

Extract from It Takes A Lifetime To Be Yourself

By Kay Carmichael

Published by Scotland Street Press

A Battered Woman and Francis Bacon

It was her fragility I first noticed. Every big city has girls like this; reared in poverty, undernourishment and fetid air. They’re like exotic, waxy orchids, pale and looking as if the slightest touch would bruise them.

I followed her down to the platform on one of Glasgow’s underground stations, she clutching a small girl in her arms – and it was only when standing beside her that I was able to see that she had indeed been bruised. Her right eye and temple had been most fearfully damaged. The flesh was swollen and broken, and she was trying to hide the whole misshapen pink and dark purple area under a fall of yellow hair.

She looked about seventeen. Her thin small body sagged under the child’s weight and both of them were dressed cheaply, but with care. The little one was a miniature of her mother. I was as certain as it’s possible to be without hard evidence that she had been battered the previous night by a man. Glasgow, it used to be said, had the highest incidence of wife battering in Europe.

On the previous day, in London, I had been to the Francis Bacon exhibition at the Tate. After an hour looking at those paintings I had come out, as one does after a powerful experience, seeing the world quite differently – seeing people’s faces in new ways: in this case their skin just holding together the deliquescent flesh. And for a brief second, when I saw this youngster’s face, I thought I was superimposing Bacon’s images on to her. But I wasn’t.

She carried her bruises and her child away from me on to the next train. If she had appeared distressed I would have spoken to her, but there was no sign of that. She was holding on to her courage and her pride, and my guess is that she was going to spend the day with her mother who would console her by describing her own and other women’s experiences of being knocked about.

Perhaps not. Perhaps she’d say, ‘Don’t allow yourself to be treated like that’. But she might be afraid of the consequences if she did that, both for her own life, because she might have to give her shelter, and for her daughter’s safety.

I keep thinking of that young woman. She’s all mixed up in my head with the Francis Bacon portraits. You wouldn’t think they had anything in common… a wee Glasgow girl and a world famous painter. But they do.

Peace Activist

Twenty-three years ago I took my daughter on the first CND march from Dunoon to the Holy Loch. This year I took my four-year-old granddaughter. She was wearing a badge saying, ‘I want to grow up, not blow up.’

I once heard Isaiah Berlin say that any institution that fails to achieve its goals in 25 years never will. He reasoned that in that time it puts down roots in the established order, which make it impossible to truly challenge it. Is CND becoming the respectable ritualised opposition which makes us all feel less guilty, more comfortable, less compelled to take any personal responsibility for nuclear weapons in Britain?

Certainly our Easter demonstration was ritualised. We paraded neatly, marched tidily, made very little noise, did what the police told us. We listened to speeches and sang a few nostalgic songs in an orderly and – if truth be told – rather desultory way. Many seemed to be there from a sense of duty rather than conviction.

Three days later I went to Dunoon Sheriff Court to hear two Greenham women being tried for offences they were alleged to have committed last January when they had come up to support a Women for Peace demonstration at the American base. I remembered that day well. It was freezing cold; the snow was thick on the ground. I had returned from sweltering Bangkok the day before. In spite of that it was a joyful and creative experience.

Three months later they brought the same spirit to the bleak, vaulted, woodlined courtroom. The women and their three friends lit the place up like birds of paradise with their gay clothes, their odd hairstyles, their vivid personalities. They both pleaded not guilty but an irascible sheriff was unimpressed by what they had to say. He imposed swingeing fines. I was left with no sense that justice had been done.

One of them, a beautiful strong seventeen-year-old, charged with malicious damage, took over her own defence. She had, in fact, sprayed the women’s symbol on the American cinema wall … Already a rather grubby wall. She said, ‘It was not sprayed, as I have been charged, ‘maliciously’. It was sprayed in defiance, in strength, because of my love of life and of the earth. I contend that I have committed no crime – the malice lies within the walls of the base…’

I hope that if my granddaughter gets the chance to grow up, and not blow up, she too will love life as much.

It Takes A Lifetime To Be Yourself by Kay Carmichael, edited by David Donnison, is out now published by Scotland Street Press priced £10.99.

You can read another extract from the book here on Books from Scotland.

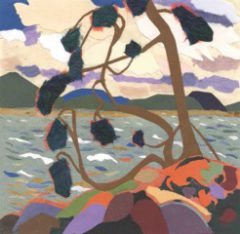

Artist Ruth MacLean’s unique collage technique showcased in a book for children brings new interpretation to, and appreciation of, the life and work of celebrated Canadian artist Tom Thomson.

Eulalie’s Journey to Algonquin with Tom Thomson

By Catherine Wilson and Ruth MacLean

Published by Ailsapress

Tom Thomson is one of Canada’s most celebrated painters. He helped to form Canada’s national identity with his paintings of the native wilderness of Algonquin Park in Ontario. Last year was the centenary of his death. He was only 39 when he died in mysterious circumstances on Canoe Lake. The new book is a collaboration of words and images by Catherine Wilson and Ruth MacLean. The story is for the older reader (8-13 years) and is told from the point of view of Tom Thomson’s dog, Eulalie. It provides a lyrical insight into the life of Tom Thomson, especially of the last five years of his life. Canadian artist Ruth MacLean has used her unique collage technique to create the illustrations, which, for the most part, are based on actual paintings of Tom Thomson. She writes of her work as follows:

West Wind

I like working with the simplicity of paper, scissors and glue. This is something that we do from kindergarten days. It is childlike, yet masterful in the hands of an artist like Matisse. One draws with the scissors. A cut has all the energy and nuances of a line. Tearing the paper makes a different and unpredictable edge. Colours and textures of paper create relationships and contrasts.

Wildflowers

For each picture I gathered papers together, like a palette. I selected Tom’s paintings from Algonquin Park that would fit into the story. Cathy’s original discovery of a “dog” shape in the rocks below the iconic pine tree in his painting “West Wind” spurred the idea of putting figures into Tom’s paintings. I call his paintings my “references”, as I loosely interpreted them, simplifying and translating them into pieces and shapes of paper. Some, like my rendition of “Three Trout” or “Wildflowers” [pictured here], were like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. Bit by bit the picture appeared, only recognizable at the end. It was fun and challenging to work with Tom’s landscapes, and it increased my great appreciation of this amazing painter’s eye and ability.

Three Trout

Printed and distributed in Canada, Eulalie’s Journey to Algonquin by Catherine Wilson and Ruth MacLean is published later in 2018 by Ailsapress. All images used here are taken from the book.

Books from Scotland gains early insight into a new book by Glasgow-based Laura Tansley and Micaela Maftei, who is based in Victoria, British Columbia. Entirely collaborative despite the distance between the authors, each story is co-written, and the collection explores themes including place and displacement. It is published by Vagabond Voices later this year.

Publisher’s Introduction

The following is an excerpt from Woods for the Trees, which appears in the yet-to-be-named short story collection co-authored by Micaela Maftei and Laura Tansley, which Vagabond Voices will be publishing later this year. It’s a unique project both in its content and its creative process, as the authors have written each story together, and have collaborated via digital methods transatlantically. As such, place and displacement form a significant element of both the authors’ process and the finished creative product. The stories that make up this collection explore how it feels to be neither/nor, how it feels to be constantly arriving or departing and never truly fixed.

What stands out with this collection is the way in which the authors explore selfhood, and womanhood in particular, as it presents itself in private and public spaces, as well as in the spaces where the two interlap. All of the stories feature real situations that will resonate with readers, yet they are written with a style and poeticism that brings everyday experiences into a more literary space.

Micaela Maftei and Laura Tansley

Woods for the Trees

At work there was a piece of post on her desk; ominous, she thought, that whatever it was required her to have a written copy. It turned out to be an invitation to management training being held in a hotel somewhere in the city centre. She spent her lunchtime trying to locate it but the chain had so many outlets she couldn’t figure out exactly where she’d be staying. Working through their automated phone system she discovered all their rooms had the same amenities anyway, everywhere across the world, so she figured it didn’t really matter.

When the car came for her the next morning there was already a passenger in it. Sunglassed and stoic, she courtesy-smiled when Christy climbed in and said nothing for three-quarters of an hour till they pulled in to a glass-covered courtyard and the driver dropped them off at an outdoor check-in desk.

“They do that on purpose you know, drop you off right at the desk. Your feet never touch the pavement and there’s no danger of anyone getting distracted and deciding they want to explore,” the woman said, slinging her suit bag off her shoulder and on to the outstretched arm of a pristine porter who shone immaculately from her hair to her leather shoes. “Give her your bags too; we have adjacent rooms. I’m Sharon.”

They were directed to a different lift than the one that the porter and their bags disappeared into. It came casually, giving Christy the chance to sit on a chaise longue and check out the enormous atrium which extended up through the centre of the first few floors like a panopticon. She hoped their rooms were higher up and had an outside view, but chances were if she had windows they would be facing another hotel just like this one; mirrored buildings copy-catted each other across the breadth of the city.

“So have you done this training before?” Sharon asked as the lift doors closed and they headed up to their rooms.

“No, why, have you?”

“My whole section is getting trained again. We’re being assessed. Restructuring.”

“Oh.”

“I did this exact series two months ago. But CPD is important to me. I’m happy for this opportunity.”

“Ok.”

“Plus I’m a fucking leader. I’m ready for this.”

From floor fifteen to forty they stood still and silent until the doors opened. Sharon gestured her out and followed her down the hall half a step behind.

“463, that’s me,” Sharon efficiently swiped her key. “See you later,” she said and disappeared.

Christy fished for her own card in her jacket pocket. Back along the corridor towards the lifts another woman waited with her back turned. Christy watched as she hitched up her skirt, turning it inside out, up and over her waist to tug at her tucked-in shirt revealing black knickers, Lycra with a kind of lace trim framing the woman’s petite butt that was perked by her black patent high heels. She righted herself, the lift arrived, she stepped in and was gone.

There was an itinerary on the writing desk in her room that said “welcome drinks at five”, which gave Christy enough time to count out the feet of her room (same as her entire flat) and change into something smart-casual. She steamed out the creases in her shirt which had collected around the curves of her shoulders in the car, but kept her hair down. She put lipstick on thinking she should draw attention to her mouth. She swapped her bra from white cotton to navy lace. She took her handbag rather than a briefcase but made sure she had a pen and notepad. She knocked on the door of the Sharon’s room thinking it’d be nice to travel down together even if Sharon had seemed odd but she got no answer so went alone. The bar was on the third floor, open-planned and looking out on to the atrium. She spotted Sharon with a glass of white wine holding court with four people surrounding her. Christy watched as she spoke, saying something which made all four laugh then leave, each scattering in a different direction. Christy picked up a red wine from a round table dressed in the company colours and walked over to her.

“Hi there, how are you?”

“Good, good. I’ve only been down here for half an hour and I’ve already made incredible contacts.”

It was only ten to five. Christy had been concerned at appearing too punctual, but had clearly missed the boat already.

“I saw you talking, were those colleagues of yours?”

“What, just now? No, no. More like acquaintances. We met at a company microbusiness and mindfulness retreat last year.”

“Oh I see.” Christy looked around and saw them all, now in different groups, engaged in conversation with other similar-looking people.

“Watch this,” Sharon said, following Christy’s gaze.

Almost in complete synchronisation, each one of Sharon’s mindful companions laughed, big open-mouthed, close-eyed flirtatious laughs, shook one or two hands, then moved to join a different group of people to start the process all over again.

“They’ll do that three or four times, then come back together to talk about how they’ve read the potential in the room.”

“Right.”

“That’s fucking teamwork.”

“So they’re not in competition with each other then?”

“What do you mean?” She wrinkled her nose at Christy.

“Nothing. I’m going to the loo.”

“I’ll join. Let’s go do some power posing before the big boss gets here.”

In the ladies Sharon picked a cubicle (she wanted privacy and was conscious of the copyright on her own poses), leaving Christy outside looking at the space between Sharon’s small feet poking out under the cubicle door as she took up some kind of superman stance.

“What division are you?” Sharon shouted.

“Corporate Concerns,” Christy said.

“Do you know Kevin?”

“Does he work in Eight or Twelve?”

“I don’t know. I made him up. Just testing.”

Christy stroked the aluminium of the faucet. It felt oddly warm.

“This has been proven scientifically, by the way.”

“What has?”

“The efficacy of power posing. I’ll be frank: ‘you’re the only one getting in the way of you’.”

Christy knew it was a quote even though she couldn’t see Sharon hands making the marks in the air.

“How do you do it?”

“Never mind. You’ll pick it up on your own, or you’ll never learn.”

Christy thought for a second then grabbed her crotch in Sharon’s direction.

Micaela Maftei and Laura Tansley’s forthcoming book will be published later in 2018 by Vagabond Voices.

We introduce the colourful story of Rose Bertin, the woman credited with inventing haute couture, who was a favourite in the court of Marie Antoinette. What would fashion today be without Bertin’s pioneering and iconic influence?

Rose’s Dress of Dreams

By Katherine Woodfine

Published by Barrington Stoke

Rose’s Dress of Dreams is inspired by Marie-Jeanne Rose Bertin (known as Rose) who was born in 1747.

When she was only 16, Rose travelled to Paris to become a dressmaker. After she began making dresses for the Princesse de Conti and other court ladies, her designs became very popular. She met France’s young queen, Marie-Antoinette and soon became her favourite dressmaker, creating many wonderful outfits for her.

But the people of France were poor and unhappy. They became angry with the Royal family and a revolution began. Soon, Marie-Antoinette was arrested and sent to prison.

Photo of Katherine Woodfine © Tom Pilston

Even then, Rose remained the queen’s loyal friend. At her execution in 1793, Marie-Antoinette wore a lace cap that Rose had made for her.

Today Rose Bertin is considered to have been the world’s first fashion designer. The incredible dresses she made continue to influence fashion today.

Author Katherine Woodfine says: “I’m so delighted to be joining Barrington Stoke’s wonderful Little Gems list, with this story inspired by the real-life Rose Bertin. As soon as I discovered Rose’s story, I was captivated by the idea of this determined young girl, forging a new path for herself in 18th century Paris – and going on to change the course of fashion history.”

Find out more about Rose’s Dress of Dreams (coming April 2018 from Barrington Stoke) by Katherine Woodfine and illustrated by Kate Pankhurt, here.

Diplomatic protocol may be well-established but its interpretation and correct application in a rapidly-changing and complex political environment could not be more relevant. Rosalie Rivett highlights the important relevance of Protocol as it applies to the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations and provides factual and anecdotal examples of this vital aspect of statecraft and international diplomacy.

Extract from Diplomatic Protocol

By Rosalie Rivett

Published by Whittles

Introduction

The delicate art of diplomacy has been used for good, even sometimes for ill, throughout history to achieve the desired aims of nations and their leaders, and to promote foreign policy. It is both an elegant art and an effective one when deployed by the finest practitioners. It is also an evolving art, adapting itself to meet a fast-moving world where events and technology are themselves moving at breathtaking speed. Diplomacy is the soft power, underlying every nation’s ambitions; without it wars could break out, peace treaties might never be negotiated or signed, and trade missions might flounder. Diplomatic protocol, it has been said, is the etiquette of diplomacy: it is one thing to want to strike up a conversation, but quite another to know how the dialogue should begin. Very often it is the diplomats who have to initiate that dialogue, even when two countries are at war with each other in an attempt to reach a peaceful and, importantly, face-saving solution. Protocol – an instrument of statecraft – is an essential part of the framework for these discussions to take place.

The world has become so small, thanks to instant communications and ever faster forms of travel, that an event on one side of the world can spark an immediate reaction on the other, and all of it instantly recorded and shared online. There is no longer time to pause and ponder while a letter or telegram wends its way from an embassy to the home nation. Reaction has to be almost instantaneous, appropriate and designed at the very least not to exacerbate what might already be a volatile situation. It has to be diplomatic and governed by established protocol – the rules of diplomatic exchange. And last but not least, it has to be media friendly.

With these changes some even question whether the role of the diplomat is becoming redundant with modern technology rendering coded messages, confidential reports and face-to-face meetings superfluous. However, as anyone who has sent or received an email or text or even tweet will know, there is the potential for misinterpretation when perhaps written in haste, simply because they were so easy to tap out and send; one must above all beware of predictive text. Technology has its place and its uses, it even has its own word to describe how it is used – ‘netiquette’ – but it must be handled with all the care a diplomat possesses, and will never, I suggest, replace the finesse of an accomplished ambassador.

The very best diplomats, I suggest, do their best work unseen by the public without drawing attention to themselves – the very antithesis of this selfie-obsessed world. They must entertain, of course, and host gatherings to mark important occasions such as national days and national cultural events, but their primary duty of representing the interests of their home government is usually conducted away from the glare of publicity.

A diplomat must be able to understand how protocol and etiquette should be applied when facing issues of cultural perception, negotiation, the increasingly sensitive area of religion and beliefs, and importantly tribal issues, which are critical in some countries and often seldom understood, if even recognised, by outsiders. With a complete understanding of these topics, any diplomat will be prepared to face situations from hosting a world summit, state or official visit by a head of state, while understanding the protocols practised by international and multilateral and multi-ethnic organisations such as the United Nations, to even more high-profile, potentially difficult and complicated situations.

When the United Kingdom voted in its 2016 referendum to leave the European Union after 40 years of membership, the impact reverberated around the world, but once the immediate shockwaves had died down it became a time for quiet diplomacy to negotiate the terms of Brexit; it is probably going to have a significant effect on worldwide diplomacy for many years to come, and it is therefore considered prominently in this book.

Brexit was one example: sadly there are regular, more brutal events which also require delicate handling, and such handling can only be achieved through preparation and understanding of the rules of diplomatic behaviour.

Diplomacy is hard work, sometimes seeking to bridge seemingly impossible divides. Speaking of the painstaking dialogue that the former US Senator, George Mitchell, tried to conduct in 2009 between the Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and the Palestinian President, Mahmoud Abbas, the then US Secretary Of State, Hilary Clinton, said: ‘As well as anyone in his generation, George understands the slow hard work of diplomacy.’

Diplomatic Protocol seeks to help its readers understand the history, role and purpose of diplomatic protocol and how it should be conducted. Without analysing the many distinct aspects and cultures of individual nations, it endeavours to offer a guiding hand to established and aspiring diplomats alike, showing how the basics of common courtesy, consideration, a willingness to understand and, finally, plain good manners will help diplomats to be themselves as they move effortlessly and effectively from post to post.

Diplomatic Protocol: Etiquette, Statecraft and Trust by Rosalie Rivett is out now published by Whittles priced £25.

In this illuminating article Juliet E McKenna casts a critical eye over the genres of science fiction and fantasy (SF&F) to determine how writers are represented, and consequently positioned, within them. Confronted with a sometimes startling lack of diversity within these genres, McKenna aims to highlight and promote understanding of these issues so that her findings bring about tangible change.

Extract from Gender Identity and Sexuality in Fantasy and Science Fiction

Edited by Francesca T Barbini

Published by Luna Press Publishing

Excerpt below from Juliet E McKenna’s ‘The Myth of Meritocracy and the Reality of the Leaky Pipe and Other Obstacles in Science Fiction & Fantasy’

It was initially assumed that increased female entry into careers such as law, medicine and higher education would naturally result in more equal representation at the higher levels over time. This has been proven not to be the case. We now see women writers and those from other under- represented racial and LGBT populations entering the SF & Fantasy genres in increasing numbers. Indeed, women have been writing in these genres since they first appeared. However, lists of bestsellers and of authors with long-term and sustained writing careers are still dominated by men. Let us consider what evidence from relevant research in other disciplines might apply to the issue of diversity in genre publishing, and see what factors might be specific to SF & Fantasy.

Studies of gender and other representation in the workplace have generated a specific jargon among human resources managers and other interested groups. For those in the SF&F world, these terms can seem equally applicable to a fantasy adventure quest.

The Gatekeeper

The first challenge is getting past the Gatekeepers. Are women and people of colour being deliberately excluded? The demonstrable persistence of such overt discrimination in the industry has demanded legislation to counter it, after all.

When looking for evidence of Gatekeepers in SF&F, it is immediately apparent that women are now well represented at the highest levels of genre publishing, as commissioning editors and editorial directors in both the UK and the US. This is not to say women cannot be misogynist or subject to other prejudices but the numbers of new books from different groups being promoted for 2017 would argue against gross, systemic bias at this entry stage. Barnes & Noble’s list of 96 titles recommended by SF and Fantasy editors (Cunningham, 2017) has 48 titles by authors readily identifiable as men, compared to the rest. The Verge website’s article (Liptak, 2017) on 33 SF and fantasy titles ‘that everyone will be talking about in 2017’ offers 18 titles by self-evidently male authors.

There is certainly no evidence that women are somehow inferior writers, compared to men. In recent years, female authors have been well-represented in both nominations and wins for all the major SF & Fantasy prizes. Between 2011 and 2015, four women won the Arthur C Clarke Award (ACCA, 2016) Women dominated the 2013 Nebula Awards (SFWA, 2013). There is similarly no evidence that readers will naturally or inevitably discriminate on the grounds of gender. Short story competitions where judges see submissions stripped of author names and other identifying data consistently produce gender balanced shortlists. This has been my own experience as a judge for a Book Club Associates competition, the James White Short Story Award and the Deddington Literary Festival. Even where authors can be identified, provided readers focus on the content above all else, gender balance follows. Epic fantasy author and best-seller Mark Lawrence has run ‘The Self-Published Fantasy Blog Off’ for the past two years, in which ten review websites assess the books submitted. In 2016, the 10 finalists were 5 male and 5 female authors, from an overall field of 300 books, of which 49% were submitted by men (Lawrence, 2016).

However this does not mean that participation is consistently equal. The Strange Horizons website’s SF Count (Cosh, 2016) has measured participation by looking at the gender balance of male versus female authors as recorded by Locus magazine’s ‘Books Received’ listings. In their 2015 report, looking at author gender in 2014, “this year’s proportion of books by women/non-binary individuals is the lowest recorded in the SF Count to date, both overall (39.9%) and in the US (42.0%) and UK (31.3%).” So are there Gatekeepers at work?

Genre editors, male and female alike, insist they would publish more women if they had more submissions from them. This mirrors findings in academic publishing when under-representation of women in journals has been examined (West, Jacquet, King, Correll and Bergstrom, 2013). Research across a range of disciplines has found that women consistently hold themselves and their work to a higher standard than male colleagues, with the result that they are far more reluctant to put their work forward for publication (Correll, 2004). Since this persistent problem is rooted in cultural issues, there is no reason to suppose that SF&F writers are somehow immune. Indeed, creative writing tutors consistently report an excess of confidence among male students compared to an excess of diffidence among women writers at the pre-publication stage.

Successive studies have also shown that academic papers of equal quality are more likely to be accepted from male authors than from women. We certainly need to consider this possibility in relation to fiction and when considering the role of literary agents. In 2015 Catherine Nichols began sending out the same novel to agents, male and female, under a male pseudonym as well as in her own name (Nichols, 2015). “Total data: George sent out 50 queries, and had his manuscript requested 17 times. He is eight and a half times better than me at writing the same book. Fully a third of the agents who saw his query wanted to see more, where my numbers never did shift from one in 25.”

Is this indicative of overt discrimination or a more subtle problem? Where under-representation in other fields has been examined, the Halo Effect has become apparent. In personnel management, this signifies the unconscious inclination of recruiters to favour those candidates who are most like them. This has long been identified as a key cause of ‘male and pale’ predominance in the upper echelons of the civil service, the judiciary, Parliament and the City of London, to name but a few. Conversely, the Horns Effect hampers candidates with significantly different backgrounds to key decision makers, where unconsciously negative assumptions are made.

How could this be relevant to SF & Fantasy? Well, the Horns Effect can certainly be seen at work in Hollywood, where ‘everybody knows’ that female-led superhero movies lack box-office appeal. The commercial and critical failure of films like Catwoman (2004) and Elektra (2005) is cited as indisputable evidence, solely on the basis of having a female lead, whenever any Wonder Woman movie is mooted (we can only hope that the recent successes of Rogue One, The Force Awakens and the all-female Ghostbusters will change this perception). Conversely, the lacklustre performance of Daredevil (2003) or Green Lantern (2011) apparently has no bearing on the ongoing multi-film projects from Marvel and DC. A broad range of explanations has been found for those particular films underperforming which have little or nothing to do with the lead star’s gender.

In terms of books, we should consider the predominance of male authors on bestseller lists and remember that publishing is first and foremost the business of selling books in an increasingly challenging retail climate. Authors consistently report rejections from agents, male and female, citing their book as lacking ‘breakout’ potential. The possibility of unconscious bias must be acknowledged, if ‘everybody knows’ SF & Fantasy written by men is more likely to sell – because that’s what everybody sees selling best. This particular Halo Effect may well influence publishing decisions, especially now that marketing departments have at least as much say as editorial in some publishing companies. Anecdotal evidence certainly suggests that female authors are encouraged by agents and editors alike, to consider writing Young Adult fiction far more frequently than their male colleagues, on the basis of established female bestsellers in that field.

This predominance of male writers in mass-market SF & Fantasy can have a further, subtle influence on gender representation. Role models matter, at the entry level and throughout women’s careers in every area where gender imbalance has been studied. Their presence is key to encouraging and increasing participation. When considering the likelihood of unconscious bias in SF & Fantasy publishing both in terms of women limiting themselves, we should return to the gender balance statistics cited so far.

The Barnes & Noble’s list of 96 titles cited earlier has 48 titles by authors readily identifiable as men but 31 by self-evidently female authors alongside 10 where gender is obscured by unfamiliar or gender neutral names, or initials. The Verge article offers 18 titles by identifiably male authors alongside 14 by women and 4 gender-neutral writers. The Self-Published Fantasy Blog Off 2016 received 300 books, of which 49% were submitted by visibly male writers, 33% by female writers and 18% gender neutral. In 2016, the 10 finalists were 4 self-evidently male and 2 self-evidently female authors, alongside 4 gender neutral through the use of initials.

So while male participation is apparent at around the 50% mark, visible female participation drops to between 30 – 40 %. Even if this gender-neutral category was actually all women writers that still means hopeful writers have fewer obviously female role models. In fact, closer examination, particularly of unfamiliar names, demonstrates that this gender neutral category invariably includes men. So male participation is in fact higher than that gender-balanced 50% or so seen at first glance.

‘Best of’ lists and articles surveying the history of Science Fiction and Fantasy persistently focus on male writers, excluding women’s contribution to the development of the genre. Where women are cited, we frequently see the same, very few, names repeated, and discussion of books often published decades ago, giving the impression that women are not currently active in a particular area. This arguably contributes to instances of agents and editors unconsciously ascribing as yet unproven potential to male authors.

Examples from magazines and the Internet are too numerous to cite. This problem was epitomised by the BBC’s recent documentary series ‘Paperback Heroes’ (Marr, 2016) which broadcast a programme on Epic Fantasy on 24th October 2016. The programme featured discussion of the work of seven major writers who were six men and one, perhaps two, women if we include the very passing reference to J K Rowling. The woman whose work was discussed in some depth? Ursula Le Guin, and the book was A Wizard of Earthsea, first published in 1968.

Four male writers were interviewed and one woman who was interviewed solely in the context of fantasy for children. Of all the writers included, adding in cover shots or single-sentence name checks, eleven men featured, compared to six women. Of those women, three got no more than a name check and one got no more than a screenshot of a single book.

All these featured and interviewed writers are deservedly popular, irrespective of genre, their books widely read, and their work is illustrative of points well worth making about fantasy. But those same points could have been made just as effectively while featuring a more gender-balanced selection of writers, from the genre’s origins to the present day. Doing so would have offered new writers a far more representative range of role models, encouraging them to try their chances with an agent or an editor.

Gender Identity and Sexuality in Fantasy and Science Fiction by various contributors is out now published by Luna Press Publishing priced £17.99. The book is a response to a Call for Papers and it explores how society, as reflected in real life, literature, movies, TV, games and cosplay, is currently dealing with gender identity and sexuality in speculative fiction, asking an important question: do we have a problem?

Juliet E McKenna’s article (above) was shortlisted for the 2017 British Science Fiction Awards.

This book explores the creative partnerships of Mary and George Watts and Evelyn and William De Morgan: Victorian artists, writers and suffragists. Raised in the Scottish Highlands, Mary Watts (née Fraser Tytler, 1849–1938) was a symbolist artist-craftswoman and designer for Liberty’s whose political activism increased dramatically in later life. Author Lucy Ella Rose delves into Watts’ important art and activism below…

Extract from Suffragist Artists in Partnership: Gender, Word and Image

By Lucy Ella Rose

Published by Edinburgh University Press

This book explores the interconnected creative partnerships of Mary and George Watts and Evelyn and William De Morgan: Victorian artists, writers and suffragists. It demonstrates how these figures worked, individually and together, to support greater gender equality and female emancipation. The Wattses’ Surrey studio-home became a meeting place for leading artists, writers and feminists of the day. Raised in the Scottish Highlands, Mary Watts (née Fraser Tytler, 1849–1938) was a symbolist artist-craftswoman and designer for Liberty’s whose political activism increased dramatically in later life.

Although Surrey was ‘rather slow to make its mark on the suffrage campaign’ (Crawford 2006: 186), significant suffrage artists and leading suffragettes resided in the Surrey Hills (especially Peaslake) where they also sourced flints for their window-smashing campaign. Peaslake was home to important campaigners including the Brackenbury sisters, artists who painted Emmeline Pankhurst’s portrait and led the pantechnicon raid on Parliament in 1908; Inverness-born, Slade-trained artist and militant suffragette Marion Wallace Dunlop, first of the hunger-strikers (1909); and Emmeline and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence (Overton and Mant 1998). Mary, a figurehead of non-militant feminism in her community, convened at least two suffrage meetings in Compton: her friend, fellow craftswoman and suffragist Gertrude Jekyll (Vice-President of the Godalming Women’s Suffrage Society) attended a suffrage meeting held by Mary at ‘Compton Picture Gallery’ (Festing 1991: 210); and a newspaper article of 1913 reports a large suffrage meeting and supper held at Limnerslease by her invitation (‘Women and the Vote: Last Night’s Meeting’, Surrey Advertiser, 29 November 1913). She thus drew political as well as artistic activity into the domestic sphere, transforming her studio-home into a suffragist meeting ground. Her presidential address on the position and potential of women is recorded:

Mrs. Watts said that with respect to the movement their common-sense side asked what are women going to get by the vote? Their higher side asked what are women going to give for the vote? The qualities which mankind had agreed to describe as feminine were love, faith, purity, and tenderness. A vote meant a voice, a voice to be heard by the State, whether in the making of new laws or in the reforming of old laws, and the millions of British women in asking for the vote were asking the State to allow them to bring to its counsel, their contribution of those higher [feminine] qualities. In answer to the question which many people were putting as to whether women would be strong enough to do this she quoted the following verse:

So nigh to grandeur is our dust,

So nigh to God is man,

When duty whispers lo! thou must,

The soul replies, I can.

Mary’s affirmative answer (in verse) to the earnest question of whether women were strong enough to be law-makers marks her role as a confident and respected suffragist leader and visionary. Her authoritative educational and presidential positions, as well as her attendance at rousing lectures by influential women in Surrey in 1891 (see Chapter 4), made her fit for this role. While Mary advocates the utilisation of ‘feminine qualities’ in the campaign and insists the state needs women’s virtuous influence (in accordance with the NUWSS), her concluding allusion to the famous final lines from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s military-themed poem ‘Voluntaries’ (1863) – which pays tribute to male volunteers prepared to sacrifice their lives in another fight for freedom – seems more suited to a speech addressed to militant suffragettes than to moderate suffragists. This call to arms couched in poetry suggests her more radical suffragist stance and sympathy with aspects of – perhaps even inclination towards – militancy in later life.

Mary’s stance at this time may have been influenced by suffragettes’ adoption of more militant tactics in their struggle for enfranchisement, strengthened by the recent death of suffragette Emily Wilding Davison (nearby in Epsom, Surrey, where the Wattses married), and driven by the ongoing imprisonment and forcible feeding of suffrage campaigners; the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ was also passed in 1913. Although the NUWSS publicly disavowed militant methods the year before Mary became President of the Godalming branch, by 1913 she may have been inspired by the renewed energy, excitement and force of early twentieth-century feminism as well as the increasingly radical discourse of the NUWSS in the Common Cause of November that year, which included war and military metaphors (Tickner 1989: 211–12). She was perhaps losing patience with peaceful and orderly suffragism in the face of women’s sustained political oppression, and starting to see milder militancy as a necessary stimulant (perhaps a moral and political duty) after decades of effort devoted to a cause she had supported for a quarter of a century. In light of George’s view that ‘all rebellion, though its extremes may shock us, is a movement, a struggle towards reform’ (1887: 27 January, 29 April), Mary may well have shared the growing suffrage ‘spirit of rebellion when it springs from intolerable injustice’ and ‘brutality of the government to women’ (Votes for Women, 28 November 1913:

Lucy Ella Rose is Lecturer in Victorian Literature at the University of Surrey. Her collaborative doctoral award from the University of Surrey and Watts Gallery supported her research on neglected women in nineteenth-century creative partnerships. A leading Mary Watts scholar, Rose has worked extensively on the Mary Watts archive at Watts Gallery and assisted the transcription of her diaries. She presents and publishes on Victorian literature, art, culture and feminism.

Suffragist Artists in Partnership: Gender, Word and Image by Lucy Ella Rose is out now priced £75 published by Edinburgh University Press.

Dina Begum celebrates Brick Lane’s diverse food cultures: from the homestyle Bangladeshi curries she grew up eating to her own luscious and indulgent cakes, from Chinese-style burgers to classic Buffalo wings, from smoothie bowls to raw coffee brownies. Begum provides a delicious recipe for Coconut and Jaggery Kheer from The Brick Lane Cookbook, and remembers how her Grandmother Nani used to make it so perfectly in Bangladesh.

Extract and Recipe from The Brick Lane Cookbook

By Dina Begum

Published by Kitchen Press

Kheer Plus Love – Food from my Grandmother’s Table

Nana and Nani in their garden, after lunch Photo credit: Roger Gwynn

In our family, Nani – my maternal grandmother — is known for the culinary skills she has passed down to my mother, who in turn has taught me family recipes that span generations. When I was a child, my late grandfather would travel two and a half hours from Birmingham to London to collect me for the stay at my grandparents’ house during the school holidays. On the journey to their home, I would wait with barely concealed excitement to fly into my grandmother Nani’s arms, anxious to be greeted with hugs and kisses and the fragrance of dishes specially prepared for my arrival.

Food is interwoven throughout my childhood memories and is the mainstay of almost every family gathering. I would sit by Nani in the kitchen while she spent laborious hours on the task of hand picking through huge colanders of vegetables that needed peeling and chopping, fish that needed de-veining and meat that needed preparation. All of these items she would magically transform into elaborate feasts. It was an unwritten rule to accommodate impromptu guests who would often arrive for dinner. Nani is a born feeder, and hospitality and generosity are as much a part of her as her elusive and shy smile.

One of the best things at my grandparents’ Victorian house was their remarkable pantry. Set under the eve of their large staircase it was the size of a small room, neatly organised for ease and practicality with various sections and compartments. Shelves were stacked with jars of homemade preserves, dried fruit, and various kinds of rice; aged, glutinous, puffed and flattened. There was a bloom about Nani every time she returned from her village in Bangladesh, with various items to restock her pantry with. Being a curious child I would spend hours exploring the items on the dark mahogany shelves. Sometime I’d open a jar and smell the mouth-watering aroma of an achaar – or pickle and sometimes I’d let grains of rice fall between my fingers, always savouring the time I spent among so many exotic ingredients, as though I was inside a very small shop. Breakfast would include ‘cheera,’ a bowl of flattened rice, steeped in warm milk, topped with freshly grated coconut, banana and glistening swirls of dark Bangladeshi molasses.

One of the dishes Nani used to make was kheer, a spice-infused glossy rice pudding made from sticky Bangladeshi rice, molasses, and coconut. Kheer is a dish that always makes an appearance during celebrations. It signifies the joy of a new birth or a new job, the welcoming of a bride or groom into the folds of a family, and sometimes acts as a sweet healer for broken hearts. Traditionally eaten during the winter season, kheer is enlivened with date molasses and coconut, found in abundance in Bangladesh.

Stirring a pot of this pudding evokes memories of childhood happiness and the pleasure of an uncomplicated dessert made with love. A hurried kheer is always evident, either too rich from cream and other unnecessary additions, or the wholeness of rice grains that haven’t had time to meld into one uniform dish. Good kheer should always be prepared with whole milk, reduced down to almost half its original quantity, with the intense flavor that comes from slow cooking. The subtle undertone of spices should also be present, and in Bangladesh these often consist of bay, cardamom, and cinnamon – the triumvirate of dessert spices, with a scent as gentle as a comforting embrace.

It’s not always easy to get hold of fresh date molasses from Bangladesh so I often substitute with jaggery, an unrefined sweetener made from palm sap and set into blocks. It is still lovely, as it has a good toffee-like flavour.

My Nani and my mother used to carve the meat out of fresh coconuts with a special frilled carving instrument. The thought of cutting and carving a coconut fills me with apprehension, so I use desiccated coconut instead. The sticky rice Nani used to use was from my grandparent’s village and I’ve not found a replacement. Basmati rice works just as well, and is easier to find and prepare.

The photograph of my grandparents in their garden was taken in Birmingham by Roger Gwynn – a dear family friend and honorary Bengali. My grandparents were asked to pose after a feast they’d hosted to celebrate the arrival in England of my mother, brother and me when I was four years old. Uncle Roger tells me that this was around the time they’d moved into their new house. Guests from my mother’s side of the family crowded excitedly around the table my grandmother had laden with dishes she’d spent days making, including dessert and her special homemade lemonade. My grandfather was a jolly person and enjoyed his food and Nani indulged him and everyone who was within feeding distance.

Even to this day, with grown up grandchildren and great-grandchildren, Nani will divide a sweet treat into however many portions necessary to ensure not one of her grandchildren is left out. Sometimes while sitting next to her on a visit I’ll find a foil-wrapped chocolate pressed into my palm and she’ll plant a kiss on my cheek saying she’d saved it for me. It is during these moments that I am thankful for the second greatest gift she has given me besides the unconditional love of a grandmother – her love of food, cooking and feeding.

(First Published in The Cook’s Cook https://thecookscook.com/ in November 2017)

Coconut & Jaggery Kheer (Rice Pudding)

Ingredients

100g basmati rice, soaked for an hour and drained

1 litre full fat milk

50g desiccated coconut

150g jaggery, crumbled

6 cardamom pods, lightly crushed

1 stick cinnamon

1 bay leaf

Add the soaked rice to a large saucepan and bring to the boil with 500ml water. Simmer on a medium heat for five minutes and then add the milk, coconut, jaggery, cardamom pods, cinnamon and bay leaf and bring back to the boil.

Reduce the heat to medium and simmer and stir continuously for 30 to 40 minutes, until the rice is cooked and broken up and the milk has reduced by almost half. Serve hot or chilled, topped with nuts or toasted coconut.

The Brick Lane Cookbook by Dina Begum is published by Kitchen Press on 22 March priced £20.

For decades, FullLife has offered the science of childbirth to everyone through the pouch. Safer. Better. Pain free. Men and women can share pregnancy equally. The pouch has revolutionised relationships and parenting. But what does this mean for society? The Growing Season speculatively imagines the profundity, empowerment, and problems catalysed by life in this brave new world.

Extract from The Growing Season

By Helen Sedgwick

Published by Harvill Secker

Audio Log

5 Jan 2016 23:15

Back then you see, when I returned to work, I was still one of the only women in the faculty. Down in the basement, where the physics labs were housed, I was studying early-stage cell development with microfluidic delivery. But King’s was an old university, theology its biggest department, and upstairs the seminary dominated.

I felt like I was being followed by those men in their cassocks and collars who paced silently across the stone courtyard. And watched. Haunted by the sound of the hymns that resonated through the labs below. When you feel you’re being judged, you imagine that same judgement is coming from everywhere. Though there was another type of haunting there, too – Rosalind died the same week my daughter was born. I was grieving for my friend, while my colleagues were still taking credit for her work. To remember how they used to make fun of her behind her back! It made me more angry than ever. I knew that if I gave them the slightest cause, they would push me out. They didn’t want me there. They were waiting for me to get something wrong, and so I couldn’t.

My work had to be perfect.

Still, in some ways King’s was progressive, for its time – in Princeton women weren’t even allowed to step foot in the physics department. Being patronised was the price we paid for walking through the door. Not that we were allowed in the staff common room. That was the backdrop, you see. That was the world I’d worked so hard to gain access too. It made me different, I think. Different from whom I would otherwise have been. All the time I had to feign a sort of steely confidence, of arrogance, if I were to get any of them to listen to me. And I had to make them listen. I felt like I was on a mission, I was so certain that I knew what had to be done.

Unusually for King’s at that point I was more interested in whole cells than in DNA – living cell research was how I wanted to study human reproduction, and I needed the engineering capability as well as the biology to sustain them. I worked with microscopes rather than X-rays, manufactured carefully designed substrates to keep my cells alive rather than wire hooks to hang and stretch molecules from. It wasn’t until after I’d built my first living cell chamber that I heard Haldane speak at the Royal Society.

He sounded smooth and assured as he talked about genetics and biostatistics, wearing a deep navy blazer with distinctive white stripes and that full moustache – it was almost a surprise he wasn’t holding a pipe. He was something of a celebrity already, being such close friends with Aldous Huxley, but it took me a moment to realise what he meant when he started going on about ectogenesis. I hadn’t read Brave New World at the time – for the best, I’d say. So as he talked about external wombs and selective breeding and child production rates I thought to myself, no, no, no, that’s all wrong – that’s such a man’s way of seeing a woman’s world. It’s never going to be about mass production in all the symmetrical sterility of a laboratory. Human beings, if nothing else, need to feel like individuals. Don’t you see? Any change must allow for individuals to remain an intrinsic part of their own reproduction, or it will fail. I wanted to create a liberating new form of pregnancy. A genuine equality. A more reliable bond between parent and child. In that moment, I realised that my work was intensely personal. That was why I was the one who would succeed.

The Growing Season by Helen Sedgwick is out now published by Harvill Secker priced £12.99.

Books from Scotland meets Moire O’Sullivan, an accomplished mountain runner and adventure racer. In 2009, she became the first person to complete the Wicklow Round, a 100km circuit of Ireland’s Wicklow Mountains run within twenty-four hours. The proud mother of two young sons, her new book Bump, Bike and Baby is about her inspirational personal journey, as Moire reveals in this Q&A…

International Women’s Day Q&A with Moire O’Sullivan

What inspired you to write Bump, Bike and Baby: Mummy’s Gone Adventure Racing?

Early last year, during a catch-up call with my coach Eamonn, he asked me if I could chat with one of his other athletes. I was surprised by his request. Eamonn never divulges the identities of those he trains, let alone providing me with their names and phone numbers.

“Sure,” I said, feeling like I owed him a favour after all the support he has given me over the years. “What it’s about?”

“Well, she’s just found out she’s pregnant,” Eamonn explained. “I thought it might be helpful if she spoke with someone like yourself.”

It was while talking with Eamonn’s athlete that I realised my experience of motherhood, though personal and bespoke, might be useful for others to hear. I figured there must be other women in similar situations, trying to learn how to become a parent while still keeping a semblance of their old identity. I thought they might benefit from reading what happened to me.

Who do you think should read your book?

For those who have not yet experienced parenthood, I hope the book gives some insight into how children can radically change them and their lifestyles in so many, often unexpected, ways.

For women who already have kids and are struggling to get fit after childbirth, I hope Bump, Bike and Baby will help inspire them to get moving again.

There may be some insight for Dads in the book also. It may help them understand what happens to their competitive wives and partners when they go through pregnancy and childbirth.

Author Moire O’Sullivan

Juggling writing, having children, and competitive sports – how do you do it?

My husband Pete and I have had many conversations about how to help each other cope with parenthood. In particular, Pete knows how hugely important training is to my psyche. Having a supportive partner, who understands that I need a daily break from motherhood in order to train, is a major component in helping me strike that balance.

I know I am very lucky that I can be a stay-at-home mum. This means that I have the flexibility to both write and train around my kids. For example, when I was writing Bump, Bike and Baby, my youngest child was taking two-hour afternoon naps. So, as soon as he dropped off, I would turn on Cbeebies to distract my eldest son while I scribbled down my personal daily target of a thousand words.

Having worked for international aid organisations as mentioned in the book, I wondered if you could tell us a bit about the differences between pregnancy in the UK / Ireland and some of the locations you’ve worked in?

I am extremely lucky in that I had the choice to give birth and raise my two children in Northern Ireland. The health care that is available is incredible, and I sincerely indebted to the NHS for providing amazing levels of support throughout my ante and post-natal stages.

Women who live in developing countries often are not as fortunate. Every day, approximately 830 women die from issues associated with pregnancy and childbirth. 99% of these maternal deaths occur in developing countries. So dying as a result of becoming pregnant is a significant reality for women living in these lower-income areas. This is a horrific reality, especially when most of the actual causes are treatable and preventable.

There are a lot of books about running and getting out in the hills written by men – how do you think we can move towards a greater number by women?

Sometimes all women need is need a little encouragement. In some cases, I sense that women don’t believe that their stories are worth telling, even though they have overcome significant obstacles and achieved incredible things. In many cases, the obstacles overcome are more significant that those at times faced by men.

So if you know a female who runs or enjoys the hills who you feel needs to tell her story, don’t just passively wait for her to do it: instead actively encourage her to write it down, and help her to spread it far and wide.

Bump, Bike and Baby: Mummy’s Gone Adventure Racing by Moire O’Sullivan is out now published by Sandstone Press priced £8.99.

Time’s Witnesses presents the histories of ten Jewish women who survived the Nazi concentration and extermination camps during World War Two. Ella Blumenthal’s brave testimony details her deportation to the Warsaw ghetto in October 1940, after which she was deported to Majdanek in 1943, then to Auschwitz and then to Bergen-Belsen, where she remained until the liberation of the camp on 15 April 1945.

Extract from Time’s Witnesses: Women’s Voices from the Holocaust

Edited by Jakob Lothe

Published by Fledgling Press

Note from the Editor

Time’s Witnesses: Women’s Voices from the Holocaust presents the histories of ten Jewish women who survived the Nazi concentration and extermination camps during World War Two. The women were born in Europe between 1925 and 1935. After the war four of them settled in Norway and became Norwegian citizens. Today, the six other women live on four different continents.

This book is inspired by Time’s Witnesses: Narratives from Auschwitz and Sachsenhausen (2006), which I co-edited with Anette H. Storeide, and which presents the stories of eight Norwegian camp survivors. By focusing solely on these two camps, we were only able to find male survivors to interview. At the same time the necessity of communicating women’s narratives became obvious. Working to present Norwegian women’s voices from the Holocaust, it is a significant problem that none of the Jewish women and children who were deported from Norway to the Nazi concentration camps returned. This is the reason why the ten Jewish women who present their accounts in this book were born in other European countries.

Working on this book has been challenging. As these challenges concern both the way the book is structured and also are closely connected to the content of the narratives, I write more about this in the introduction. Yet I would also like to stress here that although the topic of the book is dispiriting, it has been a privilege to once again meet and listen to time witnesses who have put their confidence in me by telling me their histories. They also put that confidence in the readers of this book. Time and again I am struck by the strength and courage that these ten women demonstrate by thinking back on experiences they may rather want to put behind them in order to carry on with their lives. The irrepressible will to live which helped them survive is evident in the narratives. At the same time all ten women recognise that their survival depended on chance.

Ella Blumenthal Testimony

Ella Blumenthal was born in Warsaw on 15 August 1921. Deported to the Warsaw ghetto in October 1940. Deported to Majdanek in 1943, then to Auschwitz and then to Bergen-Belsen, where she remained until the liberation of the camp on 15 April 1945. She lives in Cape Town.

In spite of surviving the Warsaw ghetto and three death camps, after the liberation I tried to integrate into a normal society, and after I had married, I raised and educated my fourchildren. But I wasn’t able to talk about my suffering and fight for survival, because the open wounds were still bleeding.

I was born in Warsaw, the youngest in a family of seven children. My father was a respected and well-to-do textile merchant. My mother and siblings were engaged in the family business. I was a happy teenager until the Germans invaded Poland on 1 September 1939.

After weeks of heavy air raids, the city of Warsaw also fell. There was panic, uncertainty and fear, particularly for Jews. New orders and declarations were coming out daily. All Jewish land was requisitioned; all Jewish bank accounts were closed, blocked. All public gatherings were forbidden; all Jewish schools and synagogues were closed. Food was rationed. Curfew wasimposed. We had to wear white armbands with a blue star on the sleeve of the outer garment.

We had to hand over our radios. Jewish men were caught in the streets to do forced labour.

My father was also one of them.

Since the synagogues were closed, daily prayers were held in private homes. He was caught in the street coming back from the prayers. When he came back home, we could not recognize him. His clothes were covered in mud, the collar was ripped out of his coat. Half of his beard was cut off. When he came back from work, he announced that he now realized that we are in the hands of murderers. Some men who did not report to work were shot…

In October 1940 we were herded into the ghetto. We managed to collect some of our belongings into sheets—like clothing, bedding, and some valuables. We did not forget our Torah, which my father managed to save from his synagogue. The rest of our possessions were looted by the Poles…

We arrived in Auschwitz in cattle trucks. Only a few years ago I found out that they didn’t want to accept us in Auschwitz. They wanted to send us back to Majdanek, as we were sick and some even dead. But the order was overruled, and we remained in Auschwitz. During our arrival there was an orchestra playing, made up of prisoners. In front of them were all the Kommandants of the camp. Among them was Dr Josef Mengele, known as the ‘Angel of Death’. Then our arms were tattooed. My number was 48 632. Below the number was a triangle; this was the symbol for a Jew. Then all our hair was shaved off. I was calling for Roma. She was right next to me, but I didn’t recognize her.

After the showers we were given lice-infested clothes and sent to a barracks where we slept ten to a stone bunk, with only one blanket. At night, the rats came out from between the bricks and crawled over us. We got used to it. They were only looking for food. Sometimes the morsel of bread I kept under my head for Roma was eaten by them.

We stood at roll calls in the rain and in blazing sun, in the snow and freezing cold. We were then counted and counted over and over until the SS woman came and received the report: so many sick, so many dead, and so many ready for work. I worked on building roads, pushing heavy trolleys, carrying heavy stones, heavy bags of sand and cement. When I think of it now, I don’t know how I managed to do this very heavy work. But I knew I wanted to survive, and therefore I had to carry on…

Roma contracted typhus and was sent to the hospital. After the third day she was warned by the woman doctor—also a prisoner—to get out because Mengele was coming, and then he always ordered all patients to be sent to the gas chamber. Roma couldn’t walk yet, but she crawled out and survived…

I still often ask myself why I was chosen to survive. Twenty-three souls of my immediate family perished. My parents, my brothers, my sisters, their spouses and eight nieces and nephews, including an infant born in the underground bunker in the Warsaw ghetto.

I will never find an answer to this question. So now, by spreading tolerance, learning and understanding, we survivors will be contributing to ensuring that these horrors do not happen again.

Time’s Witnesses: Women’s Voices from the Holocaust is out now published by Fledgling Press priced £11.99.

If one Scottish children’s author has stood the test of time, it is surely Kathleen Fidler. Adults and children alike will no doubt know her books which are still taught in schools today. This guest article explores her enduring appeal from a teacher’s perspective.

Why We Still Love Kathleen Fidler – A Teacher’s Perspective

By Claire Withers

Although she was born all the way back in the 19th Century, Kathleen Fidler is still loved today. Her stories are still read regularly by adults and children alike. They’re still found in almost all school libraries; they’re still taught in English lessons in both primary and secondary schools.

But what is her enduring appeal? Kathleen Fidler’s stories explore themes of friendship and adventure, family and adversity. In other words, all the things that still form the backbone of children’s books today.

Teachers love her tales with their familiar Scottish settings. Children can learn about aspects of history, geography and Scottish heritage. The Desperate Journey teaches pupils about the Highland Clearances, the dangers of the Atlantic voyage to the new world, and the importance of resilience in the face of adversity. The Boy with the Bronze Axe introduces children to the rich history of Skara Brae and Orcadian myths. For younger readers, both Haki the Shetland Pony and Flash the Sheepdog tell the story of the lasting and touching bonds that children form with animals.

These stories provide scope for pupils’ own imaginations to flourish. They equip them with a wider understanding of the world. How would they survive in the Stone Age Orkney Isles? What would they take with them if they had to leave their home and travel halfway across the world?

Children love to ask questions and to both uncover and imagine the answers; Kathleen Fidler’s works provide the inspiration for pupils to develop their own creative writing skills. They might bring Fidler’s striking locations into their own stories. Or, they can travel back to a different period, imagining how characters’ lives are different from their own. The bond between people and animals is a strong and relatable theme for a child, and could easily spark an idea about an exciting adventure story.

All of these ideas stem from Fidler’s own gripping stories and engaging characters – ones that are likely entertain and enthrall young readers (and their teachers!) for years to come.

More about Kathleen Fiddler

Born in 1899, Kathleen Fidler worked as a teacher and then a head-teacher before settling in Edinburgh. She wrote over eighty books for children and, due to both her teaching career and prolific writing, knew well the power a good story has on children. After her death in 1980, the Kathleen Fidler Award was established in memory of her work and to support previously unpublished authors of children’s fiction.

New editions of Kathleen Fidler’s Flash the Sheep Dog and Haki the Shetland Pony will be published as Kelpies Classics this April. Fidler’s classic works The Desperate Journey and The Boy with the Bronze Axe are available now.

New editions of Flash the Sheep Dog and Haki the Shetland Pony, by Kathleen Fidler, are published on 19 April by Floris Books priced £6.99.

Claire Withers pictured with First Minister Nicola Sturgeon at the SYP Scotland Conference in March 2018

Claire Withers is a former teacher who is currently studying for an MSc in Publishing Studies at Edinburgh Napier University. As part of her MSc she is interning at Edinburgh-based Floris Books.

International Women’s Day is a hugely important day in the year. Not only is it a fantastic celebration of women and their achievements, but it’s also an opportunity to shine a light on the struggles women continue to face around the world. Books are the perfect place to share our collective stories and reflect on our progress to an equal and brighter future. To mark the day, we asked what International Women’s Day meant to some of the Floris Books team and authors. And, most importantly, what they’re reading to celebrate.

Lindsay Littleson, Author

International Women’s Day gives us an opportunity to shout about influential Scots in history, like Dundee’s Lila Clunas, Paisley’s Jane Arthur and Glasgow’s Mary Barbour, whose actions made a positive difference to women’s lives, but whose stories haven’t been given prominence.

International Women’s Day gives us an opportunity to shout about influential Scots in history, like Dundee’s Lila Clunas, Paisley’s Jane Arthur and Glasgow’s Mary Barbour, whose actions made a positive difference to women’s lives, but whose stories haven’t been given prominence.

It’s abundantly clear from pay statistics alone that the fight for gender equality is not won. International Women’s Day is a great opportunity for all feminists to network and #PressforProgress.

I was asked to recommend a book and I’m sure it’ll be mentioned by everyone but Goodnight Stories for Rebel Girls is an inspiring read for all children.

About: Lindsay Littleson is a primary school teacher in Renfrewshire, Scotland. She won the Kelpies Prize with her first children’s novel, The Mixed-Up Summer of Lily McLean. The sequel, The Awkward Autumn of Lily McLean is out now.

Lari Don, Author

The first time I was fully aware of reading books with a focus on strong female characters and with an overtly feminist message, was when I borrowed Sheri Tepper novels from my flatmate as a student. I loved the Mavin Manyshaped fantasies (which might explain why I write so many shapeshifter stories). The book that sticks most in my mind, as a sci-fi scream against sexism and injustice, is The Gate To Women’s Country. And what does IWD mean to me? It means lots of voices speaking out about equality and respect for all.

The first time I was fully aware of reading books with a focus on strong female characters and with an overtly feminist message, was when I borrowed Sheri Tepper novels from my flatmate as a student. I loved the Mavin Manyshaped fantasies (which might explain why I write so many shapeshifter stories). The book that sticks most in my mind, as a sci-fi scream against sexism and injustice, is The Gate To Women’s Country. And what does IWD mean to me? It means lots of voices speaking out about equality and respect for all.

About: Lari Don worked in politics and broadcasting before becoming a mother and a full-time author and storyteller. Born in Chile and with a childhood spent in the north-east of Scotland, many of Lari’s books are inspired by folklore traditions from around the world. She writes for all ages of children. Her books include the award-winning Fabled Beast Chronicles, the Spellchasers trilogy, and her picture books include The Treasure of the Loch Ness Monster.

Theresa Breslin, Author

International Women’s Day is the day to celebrate, worldwide, the achievements of women. My favourite female achiever is Dame Freya Madeline Stark, Mrs Perowne, who trained as a VAD during and served with a Red Cross Ambulance Unit in Italy.

Freya Stark was born in an age when women were really not expected to venture anywhere unfamiliar on their own, far less go travelling by themselves to dangerous and wild places. She could speak many languages, including Arabic and Farsi, and read Pliny and Plutarch. Freya researched the countries she wanted to visit and off she went ‒ walking, sailing, riding camels and horses, in carts and trucks – to explore ancient lands, track the spice routes and follow in the footsteps of Alexander the Great. What is even more wonderful is that she wrote beautifully about her travels. Her book titles alone entice you: The Minaret of Djam: Dust in the Lion’s Paw: The Southern Gates of Arabia: Perseus in the Wind: The Valleys of the Assassins.

Freya Stark was born in an age when women were really not expected to venture anywhere unfamiliar on their own, far less go travelling by themselves to dangerous and wild places. She could speak many languages, including Arabic and Farsi, and read Pliny and Plutarch. Freya researched the countries she wanted to visit and off she went ‒ walking, sailing, riding camels and horses, in carts and trucks – to explore ancient lands, track the spice routes and follow in the footsteps of Alexander the Great. What is even more wonderful is that she wrote beautifully about her travels. Her book titles alone entice you: The Minaret of Djam: Dust in the Lion’s Paw: The Southern Gates of Arabia: Perseus in the Wind: The Valleys of the Assassins.

Go read the adventures of this remarkable woman.

About: Theresa Breslin is the Carnegie Medal-winning critically-acclaimed author of over 30 books for children and young adults. She lives near Glasgow, Scotland. Her work has been filmed for television, broadcast on radio, and is read worldwide.

Claire McFall, Author