After years of toil, violence, campaigning, and protesting on 6 February 1918 the women of Britain were offered their first real glimmer of equality. 100 years later, publisher Barrington Stoke celebrates these remarkable women with a book from the award-winning and bestselling author Linda Newbery – Until We Win.

February 2018 marks the centenary of the first wave of women in the UK being given the right to vote. After years of toil, violence, campaigning, and protesting, on 6 February 1918 the women of Britain were offered their first real glimmer of equality. And they’ve continued to fight for better ever since.

Barrington Stoke celebrates these women with a story from the award-winning and best-selling author Linda Newbery. Until We Win follows Lizzie, an ordinary young woman desperate for change who finds the hope that she urgently needs in the voices and actions of the protesting Suffragettes. Lizzie goes to extremes to make her voice heard and Linda perfectly captures the often fraught and dangerous lives that the Suffragettes led.

Linda says:

“I’ve often wondered what it would have been like to be a girl or a young woman at the time of the Votes for Women campaign. Wouldn’t you be full of indignation at the unfair situation? Wouldn’t you be determined that things must change? What would you do – would you march, write letters, protest? Would you break the law, like Lizzie in my story, and gladly go to prison? One thing was certain: these campaigners were never going to give in until they’d won the right to vote – never. That’s what gave my story its title.

I hope Until We Win is more than a story set a hundred years ago. It’s a story about demanding change and standing up for what you believe in. Lizzie’s fight may have been won, but there’s still plenty to campaign for in an unfair world – equality, environmental protection, animal welfare.

What changes do you want to see?”

Until We Win: They Demand The Vote by Linda Newbery is out now published by Barrington Stoke priced £6.99.

Darren McGarvey aka Loki invites you to come on a safari of sorts. A Poverty Safari. But not the sort where the indigenous population is surveyed from a safe distance for a time, before the window on the community closes and everyone gradually forgets about it. Drawing on his own experience of growing up in Pollok on Glasgow’s South Side, in Poverty Safari McGarvey powerfully delves into life in Britain’s deprived communities to call for urgent change.

Extract from Poverty Safari: Understanding the Anger of Britain’s Underclass

By Darren McGarvey (aka Loki)

Published by Luath Press

The Cutting Room

How about I take a wee shot of being the expert? I mean, I know I’m not an expert and I know you know I’m not an expert but, well, this is my book. There’s no way someone like me would have been given the opportunity to write a book like this had I not draped it, at least partially, in the veil of a misery memoir. Okay then, first, we need to create the illusion of objectivity. It seems the most effective way to do this would be to completely dehumanise my family and me, to turn my four siblings and me into quantifiable data for your rational consideration. This process should facilitate the sort of objectivity that is necessary to scientifically assess the issue. Here we go:

Four out of five have experienced alcohol or substance misuse problems at some point.

Three have a criminal record.

Three were suspended or excluded from school for disruptive or violent behaviour.

Two have attempted suicide on one or more occasion.

One has served a prison sentence for drug-related offences.

Three have never voted in a general election.

Five have experienced abuse and neglect at the hands of a care giver.

Five took up full-time smoking at a young age.

Five have received state benefits.

Five have been in a dysfunctional relationship.

Five have experienced health problems associated with poor nutrition and lifestyle.

Five have poor concentration that has impacted on their education.

Five suffer from social anxiety.

Five have experienced emotional and mental health problems that predispose them to stress.

Zero have gone to university.

Zero are on the housing ladder.

Zero have any savings.

Zero have access to a bank of Mum and Dad.

Zero are involved with an activist group.

Zero are active members of a political party.

Zero regularly visit libraries or places of cultural interest.

Zero go on foreign holidays at least once a year.

And none of us care for Radio 2, yoga or Quorn-based food products either.

It’s a lot more striking when you think about it like that, isn’t it? Beneath the specificity and uniqueness of our subjectively experienced individual lives runs a road of pure inevitability from which we rarely diverge. Poverty appears to be the definitive factor that dictates the direction of a person’s life from the very day that they are born. Studies found it was possible to predict the odds that a child will ascend to the middle class, simply by measuring their birthweight. Babies born of parents who live in areas of high deprivation are more likely to be of low birthweight compared to babies born of parents who live in areas of average and low deprivation: 8 per cent compared to 5–6 per cent.

We often discuss the issue of poverty as if it’s an entity that descends on communities at random and without warning. For some, poverty is a quicksand that consumes us despite our best efforts to escape its pull. The more effort we make to get out, the further up to our necks we find ourselves. For others, it’s a monster living on a distant hillside, a place where you should never go.

All we can ever do, it seems, is stem the bleed as this unforgiving predator moves on to its next hapless victim. I can understand this kind of emotional disassociation. I am guilty of it too when it comes to issues I’m not in proximity to. Even though it bothers me, I can understand how people who don’t live in poverty might be detached from the struggles of those who do. The social and cultural divides are often so wide that all we can do is make assumptions, drawing inaccurate conclusions about people we rarely mix with.

This disconnection, and the impact it has on our ability to think and discuss the matter, is a big part of the reason why poverty persists. Not only do we have gulfs in class to traverse, we also have divides in ideology, politics and individual and collective interests to consider. On the left, we believe poverty is a political choice, the effects of which could be alleviated if we were to redirect our collective resources to redistribute the wealth in our society. On the right, people believe that empowering the individual and the family to become prosperous, and reducing the role (and cost) of the state, is the best way to create a viable, socially cohesive society. Looming over this debate is an election cycle, mass media and a world of such unending complexity that our leaders often choose to oversimplify every aspect of our lives into soundbites. But the fault doesn’t always lie with those who remain unaware of the nuts and bolts of poverty, nor can it be pinned solely on politicians.

Being sentimental, sensationalist or melodramatic about it doesn’t help either. And just because you identify yourself as someone who is poor or someone who is ‘fighting’ poverty, that should not absolve you from examining your own beliefs and assumptions about the matter as well. It’s far more complex than many of us would like to believe.

Poverty Safari: Understanding the Anger of Britain’s Underclass by Darren McGarvey is out now published by Luath Press priced £7.99.

Chances are that you’ll know of Theresa Breslin as a much-loved author. But did you know that she’s also an active advocate for libraries? Against the backdrop of regular cuts to UK libraries today, she emphasises the need for libraries to remain abundant and open, so that they can continue to ensure access to books and other fundamental services for everyone.

Our libraries, in the great tradition on which they were first inaugurated and enshrined in the law of the land, provide access for all.

With a widening gap in household incomes, in a world where we welcome diversity, in a society where we remain humane enough to offer refuge to those in peril of their lives, the library is the safe space, which is freely open to everyone.

A professionally staffed library service delivers information literacy: enabling customers to access, research and evaluate what is presented as factual, in all the forms in which it may be contained. Specific services encourage skills in learning, personal growth and enjoyment, and social and economic development.

In addition to the provision of knowledge and information retrieval skills, our libraries are a key component in embedding the joy of reading for pleasure. Liaising with local schools and nurseries, running book clubs, organising poetry slams, arranging author visits, hosting Book Festivals and partnering with key organisations such as Scottish Book Trust, they offer a multitude of literature-based experiences to the public, which might otherwise be inaccessible.

Theresa Breslin at the National Library of Scotland

Through reading literature, we are able to think and feel at the same time. Reading widely, we build awareness of our own lives and that of others, which aids our development as mature, well-informed citizens of the world. Exposure to stories, essays and poetry from where we live, using our language, contemplating our culture, with themes and characters which resonate with our lives, is enormously self-affirming. It helps us articulate self-expression, imbues confidence, validates our life and culture, and leads to social and emotional literacy.

For the above to happen, libraries must be available and run by staff trained in selecting and promoting stock who ensure that the distribution of literature is fair and equable. Disadvantages for non-readers are significant and well documented in various reports. The cuts to book budgets, library opening hours, mobile services, local branches, and the drastic and unnecessary deletion of professional posts, strike at those most in need of a library service and those least able to protest against the cuts in that service – the less affluent, the elderly, the frail, people who are challenged mentally and physically and their carers, those who look after babies and toddlers and, crucially, our children – who are our future.

Theresa Breslin is the popular Carnegie Medal-Winning Author of over 50 books covering every age range. Her work, which includes folk tales, picture books, fantasy and humour, historical novels, modern issues, short stories, poetry and plays, has appeared on television, stage and radio, and is read world-wide in many languages. A former Youth Librarian, and Past-President of CILIPS, Theresa is passionate about children’s literacy and literature and is an active advocate for libraries. She is an Honorary Fellow of the Association of Scottish Literary Studies and was awarded Honorary Membership of CILIPS for outstanding services to children’s literature and librarianship. Her two Illustrated Treasury collections of Scottish traditional tales and The Dragon Stoorworm, published by Floris, are top sellers.

May 2018 sees the publication of Mary, Queen of Scots: Escape from Loch Leven – the story of Mary’s daring escape, packed with drama and historical detail in a spectacular children’s picture book with stunning illustrations, to be published by Floris.

Phil Anderson is an author and politician. In the aftermath of the Brexit vote, he takes a long, hard look at what really creates the conditions for people and communities to flourish and argues that radical reform is needed.

Extract from A Manifesto for Post-Brexit Britain

By Phil Anderson

Published by Muddy Pearl

If you are reading this, you probably voted to remain in the EU.

How do I know? Well partly because Scotland voted more strongly to remain than the rest of the UK. But mostly because people who regularly read books, let along people who read magazines about books published in Scotland, are overwhelming from the kind of social groups who had most to lose and least to gain from leaving Europe.

If you did support Remain, you may well be genuinely baffled by the motives of those who voted to leave. Surely, they didn’t believe those outrageous promises of sovereignty, prosperity, and billions in cash for the NHS did they? Well let me let you into a secret: it wasn’t actually about Europe. Polling carried out in Britain’s most eurosceptic areas showed that our membership of the E.U. came about number 6 on voters’ list of priorities, behind a set of far more personal and visceral concerns like jobs, housing, immigration, public services, and the economy. These people didn’t vote because of Europe. They voted because they were unhappy, disillusioned, and angry with the state of their nation, their community, and their own lives. And I know this to be true because I live in the heart of one of these communities.

My neighbours are unhappy because some of them are unemployed, and even if they aren’t their children either can’t find work at all or can’t get the kind of secure, moderately well-paid jobs which the rest of society seems to expect and which they themselves once took for granted.

Phil Anderson

They are unhappy because too many of them live on grotty, run-down council estates in badly built, poorly maintained houses. When they walk out of their front doors they experience a gloomy environment marred by litter, vandalism, and the nagging fear of crime. Those who can afford to buy their own home are unhappy because they face years of saving for a deposit followed by three decades of crippling mortgage and interest payments before they pay it off.

They are unhappy because almost half of them have grown up without knowing the security that comes from living in a stable two-parent family. They are confused about their own relationships, lack decent role models to learn from, and have discovered from bitter personal experience the pain that family breakdown causes to both adults and children.

My white neighbours are unhappy because they believe that immigrants are moving in to take away ‘their’ jobs, ‘their’ houses, and ‘their’ public services. My black neighbours are unhappy because they worry that they will be discriminated against in the workplace and that their children cannot walk the streets in safety without fear of being attacked by racist gangs.

My older neighbours are unhappy because they seem to remember a time when everyone in their street knew each other by name, everyone was a member of a local club or society, and everyone was willing to spare the time to look out for each other, and that doesn’t seem to happen anymore.

And pretty much everyone is unhappy because they are constantly being told that the world is heating up, rainforests are disappearing, the ice caps are melting, polar bears are dying, and they feel powerless to do anything about it.

This sense of unease and dissatisfaction is repeated to varying degrees across the whole of the western world. Most of the problems which afflicted previous generations are simply no longer an issue for people today. We enjoy levels of security and prosperity which our own ancestors could only dream of. But it has not made us happy and it has not convinced us that our society is entering the 21st century asking the right questions, let alone offering us the right answers.

The real challenge now for politicians and for society is not to manage disentangling ourselves from the E.U. and renegotiating our place in the world, regardless of how complex and all-consuming that task may feel. It is to fashion a vision for Britain which addresses the causes of the unhappiness and disaffection which are poisoning our lives and our communities. If we can do that, then our future as a nation is ultimately secure. And if we can’t, the next thing my neighbours vote for will make Brexit look tame by comparison.

Phil Anderson is a politician and author of Nation In Transit: A Manifesto for Post-Brexit Britain, out now published by Muddy Pearl priced £14.99.

Andy Flannagan won’t try to get you to vote for a particular party. Or indeed to vote at all. Casting an eye over food banks to debt counselling, soup vans to street pastors, Flannagan argues that although the church does amazing work treating the victims of a flawed system, it is never going to be enough, unless we show up and get involved in the decision-making process.

Extract from Those Who Show Up

By Andy Flannagan

Published by Muddy Pearl

From the Introduction

In The Simpsons, there is a fascinating episode called ‘Lisa’s Substitute’. It includes an amusing subplot set in her brother Bart’s classroom in which he and his classmates must elect a class president. Their teacher, Mrs. Krabappel, nominates the outstanding pupil Martin Prince, while Sherri and Terri nominate the less-than outstanding Bart. During a ‘presidential debate’ Bart tells a series of infantile jokes which win the support of his classmates, much to the disgust of Martin who wants to focus on ‘the issues’. Bart is buoyed by the frenzied adulation like a teenage pop sensation. The groundswell is so overwhelming that Bart is obviously going to win by a landslide. He is, in fact, so confident of his victory that he does not even bother to vote. However, his huge confidence has spread to his wide-eyed followers, who similarly do not feel the need to turn up at the ballot box. In fact, the only kids who do vote are Martin (who votes for himself) and Wendell Borton (who also votes for Martin). Nobody had predicted that the kid famed for his nerdiness and nausea would be the kingmaker!

The point here is not whether Bart should have been elected class president, or whether Bart would have made a better class president than Martin. The point is that the firmly held opinions of Bart’s classmates counted for nothing because they did not show up.

There is a difference between holding an opinion and actually expressing it. Then there is a further difference between just expressing that opinion out into the ether, and formally standing by it in something like an election. Much of our modern-day campaigning is effectively cost free. We click and share a good cause and that’s that. This book is about the intriguing adventure that happens when what we believe starts to cost us something in terms of time, effort or reputation.

This isn’t a book trying to get you to vote. It’s going to suggest that you could be voted for. Or that you could be helping someone whose name is. It’s going to suggest that, in one small way, Martin Prince could be your role model for life.

Andy Flannagan

People are hugely unimpressed with politics and politicians. The passion expressed in the Scottish referendum campaign in 2014 showed that people do care about how their countries and communities are run. The question is, will we allow those thoughts to recline as mere opinions, or will we let them take a stand? All of us know the frustration of harbouring an opinion while feeling unable to express it meaningfully. As a nation, and especially as the church, we are in danger of sliding in that direction, unless we break out of the mind-set that we will always be commentators, and never participants.

No one seems to be certain who first coined the famous phrase, ‘Decisions are made by those who show up’. But whoever first uttered the phrase, it is hard to argue with. History is made by those who show up. It always has been. Decisions are made by those who show up. Not necessarily the smartest, not necessarily the most qualified, not necessarily those of the best character, not necessarily those who may have gleaned some divine wisdom, but by those who, like Wendell Borton, simply show up. It is sobering, but perhaps also empowering.

‘Where do people show up?’ I hear you cry. They show up in a variety of places which may not always be obvious. They show up at local residents’ meetings. They show up at parents’ associations. They show up at safer neighbourhood groups. They show up at town council meetings. They show up at political party branch meetings.

When we reflect on history we do try to remember those who showed up, but our focus tends to be on the endpoints rather than the starting points. We forget that in between someone forming an opinion, and the transformation of society occurring, a lot of hard work happened. The activists in the Civil Rights Movement didn’t just believe racism was wrong. They showed up. The Suffragettes didn’t just believe women should have the right to vote. They showed up. And it cost them. We don’t often read about all the meetings that paved the way for those mass movements.

So showing up is not just about voting. Although that is obviously a good start. It’s not just about making a mark on a ballot paper, but leaving your mark on society. This is about representing yourself and potentially many others. I am suggesting that your vote could just be the start of you making significant decisions, rather than the end. Will we just follow, or, in the pattern of Jesus, might we serve and lead? Will we show up?

Andy Flannagan is a Director of Christians in Politics, and the former Director of Christians on the Left, a prophetic voice to left-sided politics and the Church.

Those Who Show Up by Andy Flannagan is out now published by Muddy Pearl priced £9.99.

Growing up in foster homes and care institutions, Alan Dapré dreamed of living in a ‘real home surrounded by books’. In reality, the few books he had, he treasured. In this revealing account Alan, a prolific author, makes an impassioned case for enabling all children to read, and have opportunities to excel, regardless of circumstance.

What do the Superman And Batman Annual and The Guinness Book of Answers have in common? They’re the only books I possess from my childhood. One thrilled my young mind with its heroic tales of action and adventure. The other filled it full of surprising facts.

If I had to choose between the two, the superhero annual means more to me. When I open the cover I can see five handwritten words: ‘To Ian, love from Alan’. It’s the only example I have of my childhood writing. At some point, Ian crossed the words out and wrote ‘To Alan from Ian’ – and the book became mine once more.

I spent my early years in foster homes and care institutions. Most of the things I carried around on my travels were left behind at some point. In one children’s home, I carefully chained my 1970’s second-hand Chopper bike inside a dark coal shed. Then I was dispatched on yet another fostering. When I returned I discovered the front wheel was still chained up. Just the front wheel, mind. The rest had gone. It was never wise to leave things behind.

It’s hard to settle down when life is so turbulent. It’s hard to have privacy, especially when you share a room with other children. I remember being given a metal torch for my seventh birthday and sneakily reading under the bedcovers. It made a change from staring at passing headlights out of a window. I’d gaze out and imagine myself being carried away to a real home where I would be surrounded by books and toys and love.

Alan Dapré

Most of the books in my first care home were unloved. They lurked on a narrow set of bookshelves behind a black and white television. Their cracked leather covers bore un-enticing titles like Little Women or Anne of Green Gables. I read them all with varying degrees of enthusiasm. Once, an old Rupert Bear annual appeared and I eagerly read it until the pages dropped out. I preferred the colourful, well-stocked library in my primary school, where I discovered incredible books like The Wizard of Earthsea and Stig of the Dump.

Imagination is powered by books. They open up young minds, raise hopes, banish fears, give children control. They certainly anchored me while my chaotic home life whirled all around. But if books are to have a real impact, they have to play a meaningful part in young lives. I’m always delighted to read about important initiatives that put this into practice. It shows children in care that others care.

The Scottish Book Trust is a proud partner of Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library, which provides a free book a month to all looked-after children in Scotland up to the age of five. They’re encouraged to build a personal library of up to 60 books. The youngsters involved are able to read and cherish well-written and beautifully illustrated stories. How good is that?

Other organisations are keen to promote the power of stories. CELCIS [the Centre for Excellence for Looked after Children in Scotland] recently ran Get Write In! – a creative writing competition for looked-after or care-experienced children. Inspired by the theme ‘Random Moments’, the children who entered wrote funny, poignant and powerful pieces – from the heart and their own experiences. The act of submitting an entry takes courage and self-belief. I was impressed by the number of children happy to express themselves through words and stories. I would have loved a chance to do that at their age.

Life is not a level playing field. Children do not have equal starting points or opportunities. So it’s up to us adults to step in and provide creative young minds with opportunities to excel and be the best they can be.

It’s not rocket science. That’s on page 151 of The Guinness Book of Answers!

Alan Dapré is the author of more than fifty books for children, most recently the Porridge the Tartan Cat series, published by Floris Books. He has also written over one hundred television scripts, transmitted in the UK and around the world. His plays have been on BBC Radio 4 and published for use in schools worldwide.

Find out more about the CELCIS GetWriteIn! Competition on their website.

You can read an extract from Porridge the Tartan Cat and the Brawsome Bagpipes here on Books from Scotland.

Interview with Patrisse Khan-Cullors, author of When They Call You A Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir

Championing human rights in the face of violent racism, Patrisse Khan-Cullors is a survivor. She is also a founder of the Black Lives Matter movement, which seeks to end the culture that declares Black life expendable. In this interview, the perfect introduction to her new book When They Call You A Terrorist, Patrisse talks candidly about living in America, the era-defining movement, and much more.

When They Call You A Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir by Patrisse Khan-Cullors and Asha Bandele is out now published in hardback by Canongate Books priced £16.99. The audiobook version is available on various digital platforms and in CD format.

This extract from Catherine Czerkawska’s book For Jean gives background to Burns’ famous tempestuous relationship with Jean Armour, while giving insight into the woman behind ‘Jeanie’ as she was often called in the bard’s poetry.

Extract from For Jean: Poems & Songs by Robert Burns

By Catherine Czerkawska

Published by Saraband Books

My novel The Jewel explores the dramatic relationship between Robert Burns and Jean Armour, the woman who, after a long and tempestuous courtship, finally became the poet’s wife. Many biographers and critics have not been particularly kind to Jean. Burns’s lover Margaret Campbell – or Highland Mary as she’s more popularly known – was much more appealing to Victorian sensibilities as the demure heroine, conveniently dying young and depicted gazing adoringly up at her lover in a dozen Staffordshire flatbacks.

Similarly, the poet’s overheated letters and beautiful poems to Nancy McLehose, aka ‘Clarinda’, are intriguingly mysterious. Did she succumb to the poet or not? Only the two people most closely involved could say for sure, and they never revealed the secret. Jean and Nancy did, however, take tea together some years after the poet’s death, although I can’t imagine that Nancy was moved to speak about the details of the relationship.

However, accounts of ‘Jeanie’ often range from dismissive to downright insulting. She has been called everything from ‘glaikit’ (foolish) to an unfeeling ‘heifer’.

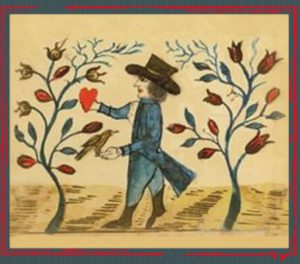

Detail on For Jean’s cover

The best-known painted portraits of Jean Armour show an elderly woman, her strong face marked by ill health. There is a much more sympathetic picture of Jean as a widow, probably in her forties and very much at ease with herself, but what seems to be missing from most images and accounts is Jean’s vitality. She was a vivacious brunette with a kindly manner, a steadfast generosity and a fine singing voice. Moreover, she had a fund of songs and melodies with which to enchant the lover who was to become her husband.

She may not have been scholarly, but she was certainly literate, as were her girlhood companions, the ‘Mauchline belles’, the self-consciously superior lassies of the town with their interest in fashion and novels. Later, her wisdom and strength of character in coping with her husband’s infidelities, his moods, his illness and early death – not to mention the ever-present threat of poverty – speak to us of a woman of spirit and fortitude. And all while bringing up a family of children, including the poet’s daughter by another woman.

Until now there has been no single collection of the poems Robert Burns wrote with Jean Armour in mind, or at the very least with memories of their courtship informing the lyrics. It will be clear to anyone reading these poems and songs – as well as the letters – that Rab and Jean’s love for one another was real and abiding, even though they may occasionally have fallen out of liking.

***

I’ll Ay Ca’ in by Yon Town

I’ll aye ca’ in by yon town,

And by yon garden green again;

I’ll aye ca’ in by yon town,

And see my bonie Jean again.

There’s nane sall ken, there’s nane can guess

What brings me back the gate again,

But she, my fairest, faithfu’ lass,

And stownlins we sall meet again.

I’ll aye ca’ in, &c

She’ll wander by the aiken tree,

When trystin time draws near again;

And when her lovely form I see,

O haith! she’s doubly dear again.

I’ll aye ca’ in &c

(Tune: I’ll Gang Nae Mair To Yon Toun)

***

This song recalls the secret meetings between Robert and Jean, when Jean’s parents disapproved of the poet. Certainly, even while Robert was in Edinburgh and was writing love letters to Nancy McLehose, he was still arranging the occasional ‘tryst’ with Jean: he could never quite keep away.

The town of the song is presumably Mauchline and we know that the couple was in the habit of meeting in the countryside round about. It may be that for Robert, the ‘garden green’ is the garden of Netherplace House on the edge of the town.

stownlins: in a secretive manner

aiken: oak

trystin: meeting or assignation

O haith!: exclamation of surprise

For Jean is a new collection of Robert Burns’ poems and songs written for his wife, Jean Armour. This volume also includes a chapter of his letters to, and about, Jean. Both verse and correspondence cast fresh light on their relationship. For Jean by Catherine Czerkawska is out now published by Saraband Books priced £7.99.

Glowglass by Kirkland Ciccone is about a new beginning – a chance to start afresh. Starrsha Glowglass has grown up in a cult. Suddenly and dramatically her world has changed, unleashing exciting opportunities. But, as everyone who has done a SWOT analysis knows, Opportunities are followed by Threats… We spoke to author Kirkland Ciccone ahead of publication of his new book for young adults.

Where did the idea come from?

I wanted to write a story about a girl with secrets, which sounds like a good start for any Young Adult (YA) novel. The word ‘Glowglass’ came to me one night whilst scribbling notes and I had no idea what it meant. I love it though. What does it mean? Does it mean anything? But that’s how inspiration works. I decided it would be the surname of my protagonist.

I also wanted to write something to do with Hipster Revivalism. You see it in the supermarket with vinyl records being sold next to the hair dye, and you also see it in YA novels like Tape and 13 Reasons Why. There’s a certain vogue with tape cassettes, records, and other old tech.

Finally, I had a notion to write a book in Second Person Narrative. I ended up having the main character Starrsha speaking directly to the reader. Starrsha Glowglass is from a small cult, a technologically-backwards religion that has been invented by her father as a tax dodge. So of course she would narrate the book through a rubbish old camcorder. It isn’t just a stylistic choice on my part. It actually helps the story unfold as readers will see for themselves.

Through the novel, I say a few things about the world around me. Nobody escapes my books unscathed.

How does Glowglass sit alongside your 3 previous novels – Conjuring The Infinite, Endless Empress and North Of Porter?

My books are punk in spirit. It’s really important to me that I feel like I’m doing something a bit different.

I write quirky books and Glowglass is another one. Quirky seems to be more palpable to readers than ‘weird’. The only book of mine I think veers into outright weirdness is Endless Empress, which is probably my favourite alongside this one.

Glowglass has some noticeable similarities to my other novels. There’s a twist in the tale – I love plot twists. I’d rather have a plot twist than a twisted ankle, that’s for sure.

There are also themes of peer pressure, bullying, secrets and lies in all my books. There’s often a sense that…what you think you know is completely wrong. I think Glowglass sits quite snugly alongside my other books in that respect.

The main difference is that the structure is quite different. I’ve really cut out all the fat in my writing. There are 100 chapters in Glowglass, some short, some a big longer. If readers don’t like it, I’ll stamp my feet and yell loudly.

Author Kirkland Ciccone

Do you hope that Glowglass will prompt discussion of particular issues?

I think a few readers will look at the characters and see themselves, or recognise certain situations.

The great thing about YA fiction is that we’ve all been to school, so the themes of my books are universal.

The other discussion it may prompt is in on of the subject matter. I don’t want to label Glowglass an LGBT book, because that’s only a small part of the novel. But it certainly takes the ‘L’ from LGBT and uses it in one of the characters. Greater emphasis in LGBT fiction for teens is usually placed on the G, B, or T parts of the acronym. Glowglass is my small way of contributing to the ‘L’ of LGBT fiction for teens.

I’m also unsure teens will look at Vloggers in the same way again once they’re introduced to Cassandra Louella Trent, AKA Cassie Trendy, the hippest girl at Morvern High, who has her own YouTube channel. I had a lot of fun writing that character.

I think readers can tell when I’m really having fun with my creations. Campbell Devine from Conjuring The Infinite always makes me laugh, because he’s utterly ridiculous. As does Portia Penelope Pinkerton from Endless Empress.

I hope my fans take to Starrsha Glowglass and enjoy her story.

Porridge plays an important part in this story. Food heaven or food hell?

Hell. I hate porridge. No matter how many times it gets rebranded or sexed up, it’ll always be sludge in a bowl.

I have a habit of bashing anything I hate in my fiction. It happens in Endless Empress when a character feeds people sandwiches laced with hallucinogenic drugs. There’s also a bus that’s never on time in that book and a really bad Elvis impersonator. North Of Porter satirises z-list celebrities and the effects of the recession. Glowglass takes aim at annoying YouTube Vloggers, bad fashion, the current obsession with retro technology, and…not organised religion, but disorganised religion.

Where does your love of howdunnit and whodunnit stories come from?

I’ve got so many references and inspirations.

Conjuring The Infinite is my love letter to all the books, TV shows, and movies that scared me as a child.

But one thread that runs through all of my fiction is that there’s always someone up to something – a killer lurking, a mystery to be solved. That came from Agatha Christie. I used to watch episodes of Poirot on a black and white TV nearly thirty years ago as a small child in Cumbernauld. I was the only person in my school interested in Poirot. They were all watching Home And Away. “No,” I’d scream, “watch bloody Poirot!”

Conjuring The Infinite has such a great twist and no-one to my knowledge has seen it coming. Obviously I won’t reveal it here, but I’m so proud of it. Blame Agatha. She was an absolute genius at misdirection.

Glowglass by Kirkland Ciccone will be published on 3 May by Strident Publishing priced £7.99.

Gavin Dobson takes us behind the scenes of his forthcoming novel The Road to Givenchy to reveal how his family in Edinburgh inspired him to write this compelling story about the Scottish soldiers that went to France to fight in the First World War.

The Road to Givenchy: The Story behind the Story

By Gavin Dobson

As a young boy I often visited my maternal grandmother, Winifred. Her house in Newington became a gathering place for her sisters—my great aunts. In their soft Highland voices, they told stories of their young brother, killed in France in 1915 at the age of 20, and of his many friends who never came back.

My grandmother was the only one to marry and have children. Her sisters lost their boyfriends and sweethearts in the mud and gore of France. They became successful teachers and led fulfilled and useful lives, but always seemed haunted by their sense of loss.

The same trauma pervaded my grandfather’s family, whose youngest boy died from his wounds in 1919.

Each boy was the apple of his family’s eye. They were scholars, athletes; witty, handsome; but cut down before they’d had a chance to prove their brilliant futures. Thus, I felt compelled to write this book.

Harry Mackinnon is a composite of the two young men who perished: a son of the Manse, a scholar who wins a fellowship in 1914 to a Belgian university to help catalogue ancient manuscripts. In the months leading to the outbreak of war he befriends a young German and falls in love with the daughter of his hostess. He is caught up in the excitement and turmoil of France in the early days of war.

Above all, Harry is the embodiment of the talents, charm and lost gene pool of a brilliant generation.

I stress that this book is pure fiction, though set in a recognizable historical framework. When I state that something of historic importance happened on a particular date, it did. The political count-down, the military training, the battles, the civilian outrages, are all, to the best of my research, as accurate as possible to lend authenticity to the story.

The Road to Givenchy by Gavin Dobson is published in June by Strident Publishing priced £8.99.

A special guest post celebrating the bard, and introducing a new interpretation of his work for children, by Floris Books.

It’s only a week to go till Burns Night arrives amid a flurry of haggis and tartan, whisky and poetry. Perhaps some of our readers are seasoned bards themselves, able to recite Tam O Shanter backwards and know a mouse from a louse when they see one. Or perhaps you’ve never encountered the Scottish bard before? Whatever your feelings about Burns, Scotland’s most famous writer has endured unfalteringly in the national conscience of the Scottish people for over 250 years. From Edinburgh to Aberdeen and from the West Coast to the East Coast, countless school children have been reading and reciting the poetry of Rabbie Burns in the run-up to January 25th.

However, January is not only an opportunity to remember Burns, but to reflect and reconsider Burns’ work in a new light, something which the Floris Books edition of My Luve is Like a Red, Red Rose sets out to do.

In this beautifully illustrated picture-book version of Burns’ classic poem, the lyrics have been re-imagined to explore the special love between a parent and their child, specifically a mother and her daughter. Featuring everyday scenes, from playing in a garden to splashing in the sea, each scene is inspired by Burns’ original, eloquent words.

With delightful, heart-warming illustrations by Ruchi Mhasane (illustrator of The Selkie Girl), this new edition of the famous poem reveals the multi-layered depth of meaning that can be found in Burns’ verse and how different readings of the poem can enhance our understanding and appreciation of Burns as a writer.

It’s clear that the team at Floris Books, based in Edinburgh, are all hugely passionate about the work of Robert Burns and believe that it’s valuable and relevant to share his work with children from a young age. In resituating the classic romantic verse of Red, Red Rose within the context of familial love and the everyday, this new edition encourages children to enjoy poetry and books, including the Classics, whilst offering parents a way of expressing their love for their children.

We asked Senior Commissioning Editor, Sally Polson, where the idea for this new edition of the classic poem came from. “The inspiration emerged from observing how young children respond to the rhythm and repetition of poetry. Though they may not fully understand the content, these literary devices enable them to enjoy classic poetry that may at first have seemed too challenging. This led us to thinking about how the context of this poem could be changed to reflect the lives of young children and parents, without altering the words and their message about the intensity of unconditional love. As with many of Burns’ poems, this poem originated as a song, so the rhythm, use of repetition and strong imagery make it ideal for a picture book adaptation for young children.”

Asking the team how they felt about publishing this new edition of Burns’ poem, they said, “We believe it’s important to keep revisiting classic works and providing alternative perspectives. Many of us, in the office, have children ourselves and empathise with this re-reading of the original poem, which we feel is just as valid as the more traditional interpretation of romantic love. This book will allow parents and their children to rediscover Burns in a completely new way, meanwhile nurturing the next generation of readers and writers. By introducing young readers to writers like Burns at an early stage in their lives, we’re opening the door to a wealth of literature, culture and ideas.”

Finally, we ask the team whether they’ll be reciting any Burns for Burns Night. Unsurprisingly from this proudly Scottish publisher the answer is a resounding, “Yes!” However, as the team have proved, Burns is not just for one night only. In fact, My Luve is Like a Red, Red Rose is an ideal gift for Mother’s Day or Valentine’s Day and one that ought to be treasured throughout the year.

My Luve’s Like a Red, Red Rose is available from Floris Books priced £6.99.

The Walrus Mutterer is the first book in The Stone Stories trilogy. Set in the Iron Age, Rian, a carefree young woman, is enslaved by a powerful trader and taken aboard a vessel for a long and perilous voyage. Sample this exciting new intergenerational saga, which spans time and continents, below…

Extract from The Walrus Mutterer

By Mandy Haggith

Published by Saraband Books

In the morning everything was frozen: the drinking water barrel, blankets, ropes, deck planks, benches, boots, coats, toes, fingers, tears. Even the sea.

Faradh’s nose froze. He cried. He buried himself in his bedding roll. Li wrapped himself around him to try to keep him warm.

Ussa strode the length of the boat wrapped in her polar bear coat. She was a pacing fury. Sometimes Pytheas paced with her.

Toma stood at the tiller, chewing. Periodically he said something. Rian heard him say it over and over, not knowing what it meant. He was saying it to Ussa and to Pytheas. Eventually he said it differently and something changed. Rian did not know what it was.

Og said, ‘Thank the Mother.’

Toma came and stood over her. She closed her eyes so as not to have to see him. But he tapped her on her shoulder. She looked through him, but his face was that of a seal and it drew her gaze. He was holding out a piece of the whale meat he chewed, offering it to her, and then he hummed, bringing his face close to her right shoulder so she could feel his breath on her neck. He hummed almost inaudibly into her ear the song he had sung to the whale. Staring at her, wild eyed. Tugging her out of herself.

She reached a hand out from under her blanket and took the meat. She curled her fingers around it and closed her eyes again. Her hand retreated with its gift under the blanket. Toma gave an insistent poke. She resisted, then lifted her lids. He pointed out on deck, and then touched her lips with a feather touch. His eyes spoke. ‘Come.’

Something in her decided to accept the challenge. She allowed him to pull the puppet inside her and to do his bidding. She was, after all, only a slave now.

They were sailing towards the sun and the sea was milky. They were among an archipelago of ice islands. Everyone was looking to the right. A white bear was ushering two cubs away across the ice, looking over her shoulder at the boat and striding purposefully away, her two followers scampering to keep up. At the edge of the floe she poured herself into the water and the cubs splashed in after her. She let them climb onto her back and swam off. Before long she was swallowed into the seascape, a blur, a dot, gone.

Rian’s attention returned to the ice. Near to the water line it was translucent blue. The pieces ranged in size from large plates to small islands. They were all, subtly, in motion, a teeming yet inanimate hoard in a bath of jade green sea.

A seal with a frozen moustache lying on one of the ice slabs regarded them with curiosity but no fear. Another, closer, slid into the sea. Two kittiwakes flew by, tilting sideways to get a better view of them.

The boat nudged its way though slush and Toma began to sing the free spirit song. Rian joined in and let her voice escape out over the freezing ocean.

Ahead of them a sea spirit with a single-horned head lifted from the water, puffed and rolled back under, showing them the way. Toma had taken over the tiller from Li, who moved between the ropes, tightening, slackening, keeping the sail taut with the breeze behind them. It seemed to be helping. Li did not sing, but he pointed to the water where the creature had been and breathed its name. ‘Narwhal.’

The Walrus Mutterer by Mandy Haggith is published by Saraband on 21 March priced £8.99.

How do we begin to narrate the history of the world? Where do we start? Where do we end? In Fireflies Luis Sagasti attempts to answer these questions and more in this unusual and thought-provoking novel.

Extract from Fireflies

By Luis Sagasti; translated by Fionn Petch

Published by Charco Press

The world is a ball of wool.

A skein of yarn you can’t find the end of.

When you can’t, you pluck at the surface to bring up a strand and then break it with a sharp tug. Once you find the other end, you can tie the two threads of yarn together again. One of grandma’s little tricks.

Some people think the world is a ball of wool from a lamb that sacrificed itself long ago so everyone could stay warm.

And they find this idea comforting.

And there are others who think that, in fact, the world is held up by threads. As if the ball of yarn were elsewhere. So headlines appear that try to explain things like who pulls the strings of the world. Magazine covers: two threatening eyes against a black background. And there are writers who write whole books about this. Conspiracy theories. An explanation that arises from intellectual laziness: the idea that a shadowy group has chosen to weave the plots of all of our lives. Just like that. Because: a.) they are pure and good; b.) they want to keep hold of their wealth; c) they are evil, really evil; or d) they hold a secret that would be the end of all of us if we were to find it out – and of them too, of course. For those who see the world this way, any conspiracy – because there have always been conspiracies – is just the visible result of a greater conspiracy. And the smaller conspiracies are all interconnected. Man never reached the moon. Paul McCartney died in 1967 and was replaced by a lookalike. Christ descended from the cross and had twins with Mary Magdalene. Shakespeare’s works were actually written by Francis Bacon. The Lautaro Lodge was a branch of the Freemasons, who are a branch of the Rosicrucians, who are a branch of the Gnostics, and the tree proliferates so wildly that not only does it leave us unable to see the wood but it also fills everything with shadows, making way for those two threatening eyes that want us to understand that there’s something out there it’s better we don’t know about. Because – and this we do know – conspirators always leave clues, as if everything were one big game of hide and seek. For people who think like this, any secret is part of the plot because when people conspire they breathe low and in unison, as if whispering a secret.

We shouldn’t believe them, though it’s right to believe in secrets. After all, childhood is nothing but the progressive revelation of well-kept secrets. To reveal them all at the same time would be to reveal nothing. The darkest dark and the whitest light are equally blinding. As is discovering that your dad has already bought all your Santa presents for the next five years.

How do we know when there are no more secrets? When do we find that out? Or is there nothing to learn?

There are secrets that make the world work in a particular way. But they shouldn’t be called secrets. Omissions would be more prudent. For the machine to keep running, it’s better not to mention certain things. Every family holds a terrible secret that, as soon as we sense what it might be, is no longer mentioned.

And there are still others who believe that these threads in fact sustain the world from the inside, as if the world were the great ball of wool and we were insects, like ants or flies, crawling or flying around it. A ball of wool someone is using to knit something. Or perhaps no one is knitting anything at all. There’s just a great shroud with no Penelope, growing without purpose in the eternal silence of infinite space.

One thing we can be sure of is that, for hundreds of thousands of years, the ball of yarn has been revolving without pause.

Fireflies, by Luis Sagasti and translated by Fionn Petch, is out now published by Charco Press priced £8.99. The book launches at Edinburgh’s Golden Hare on January 19th; get your ticket here.

Fireflies, by Luis Sagasti and translated by Fionn Petch, is out now published by Charco Press priced £8.99. The book launches at Edinburgh’s Golden Hare on January 19th; get your ticket here.

Acclaimed writer and poet Jorge Consiglio presents a universe of seemingly unrelated tales in Southerly. Here, in 1912, we meet a group of immigrants arriving in Buenos Aires, in search of a new life.

Extract from Southerly

By Jorge Consiglio; translated by Cherilyn Elston

Published by Charco Press

In June 1912 a merchant ship was delayed entering Buenos Aires. During the hours they were kept waiting, the passengers – all on deck – gazed ashore in search of clues about what the future held. They saw cranes, silos, a group of freezing people (the temperature was -2°C) and the serrated outline of a tower. Everything else was shrouded in fog. The chaotic disembarkation represented the conclusion of one chapter of their lives. Yet the minds of the new arrivals were already fixed on the next one. They believed that life was just beginning, that they were starting anew. A young man – tall, stocky and redheaded – broke away from the crowd and strode across the port as if he knew where he was going, heading towards the streets of the city centre. His name was Czcibor Zakowicz. He carried a cardboard suitcase and was wearing a duffel coat. In his pocket was a piece of paper with a name and an address on it. A distant relative, the cousin of a cousin, was expecting him and would put him up and feed him. Zakowicz would do the rest. He found work at a cabinetmaker’s and, in a short time, discovered his relationship with wood was not that of a craftsman. He was organised and successful. He set up a workshop in the Flores quarter and found a talent for inventing fanciful myths. He combined work with tradition and sacrifice.

After he turned forty-five, his eyebrow hair began to grow. It became a wild, unkempt thicket that covered the ridge of his brow, curving downwards into his eye sockets until it brushed his eyelids. In the first few years, Czcibor Zakowicz tried to domesticate his brows. He trimmed them every week, more out of embarrassment than vanity. However, it is common knowledge that laziness tends to get the better of even the most determined. Eventually, Zakowicz became resigned to his appearance, and something changed in the look in his eyes.

The same thing happened to one of his grandchildren, when he turned fifty. He inherited his grandfather’s overflowing eyebrows, and suffered similar embarrassment until he in turn conceded defeat. He also inherited his grandfather’s sense of urgency, which had made him ambitious in his career. He was an estate agent. In keeping with family tradition – a romantic absurdity – they called him Anatol, and that is how his name was recorded on his birth certificate. He, a skilful operator, took advantage of the exoticism of his name – not his surname but his first name – and turned it into a brand. It was the perfect combination of something both straightforward and unusual, two decisive factors when it comes to selling properties in fashionable neighbourhoods. Anatol, married to a very light-skinned woman, understands like no other the secret of his era, its fickle essence. His company’s logo, for example, is adapted from a nineteenth-century Danish ex libris with text in the Garamond typeface. The efficacy of maximising artifice, an aesthetics of defiance, of bravado. All coming together as one great, effective masquerade. Nothing is concealed from the client, not even their own stupidity.

Excerpt from the book of short stories also entitled Southerly by Jorge Consilgio (translated by Cherilyn Elston).

Excerpt from the book of short stories also entitled Southerly by Jorge Consilgio (translated by Cherilyn Elston).

Southerly is out now published by Charco Press priced £9.99.

In this book published by National Galleries of Scotland we explore the life and influential art of Phoebe Anna Traquair, whose vibrant modern style helped catalyse the birth and flourishing of women artists in the nineteenth century.

Extract from Modern Scottish Women: Painters & Sculptors 1885-1965

Edited by Alice Strang

Published by National Galleries of Scotland

In 1885 Sir William Fettes Douglas, President of the Royal Scottish Academy, declared that the work of a woman artist was ‘like a man’s only weaker and poorer’. Yet between 1885, when Fra Newbery was appointed Director of Glasgow School of Art and did much in terms of gender equality amongst his staff and students, and 1965, when Anne Redpath, the doyenne of post-Second World War Scottish painting died, an unprecedented number of Scottish women trained and worked as artists. This book focuses on forty-five Scottish female painters and sculptors and explores the conditions that they negotiated as students and practitioners due to their gender.

PHOEBE ANNA TRAQUAIR 1852–1936

Born Dublin 1852; died Edinburgh 1936

Studied Royal Dublin Society School of Art 1869–72

HRSA

Phoebe Anna Moss was born in Dublin, the sixth of the seven children of Dr William Moss and Teresa Richardson. At the end of her training at the Royal Dublin Society School of Art she was invited by her tutor to illustrate the research papers of Dr Ramsay H. Traquair, a Scots palaeontologist employed by the Royal Dublin Society. She married him in 1873 and henceforth would prepare all his fossil drawings. In 1874 the couple, then expecting the first of three children, settled in Edinburgh on Ramsay’s appointment to the Museum of Science and Art.

Traquair’s Edinburgh art initially took the form of domestic textiles, but in 1885 she was invited by the Edinburgh Social Union to decorate the walls of the Royal Edinburgh Hospital for Sick Children’s mortuary chapel. This kick-started a professional career which would always straddle fine art and craft. She painted two other Edinburgh buildings – the Song School of St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral (1888–92) which made her name in London (thus gaining her husband’s respect) and the vast Catholic Apostolic church in Mansfield Place (1893–1901, now the Mansfield Traquair Centre) – plus two English churches in the 1900s and 1920s.

Phoebe Anna Traquair, The Shepherd Boy, 1891 (detail). Oil on canvas, 19.8 x 24.5 cm

Physically petite and of a determined temperament, Traquair often sought out people with whom to debate ideas. She wrote to the famed critic John Ruskin to seek advice about illuminating manuscripts in 1887, and soon after befriended John Miller Gray, the first curator of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, and fellow artist William Holman Hunt.

At the height of her career, in the 1890s, when she established her reputation as Scotland’s leading Arts and Crafts artist, Traquair used every available hour to make her walls ‘sing’, to work alone on book art or with fellow bookbinder friends at the Dean Studio in Edinburgh’s West End, or, late at night, to stitch art embroideries at home. She showed at the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) from 1893 and the Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts (Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts from 1896) in 1895, a year when she also exhibited at Glasgow’s massive Arts & Crafts Exhibition. In addition, she regularly contributed to London’s Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society from 1899, joining it in 1903, and to smaller Scottish craft displays, as well as at the World’s Fairs in Chicago in 1893, Paris in 1900 (with the Guild of Women Binders) and St Louis in 1904. W.B. Yeats noted that all her work narrated life’s journey. Drawing frequently on different cultures and much inspired by William Blake or Dante Gabriel Rossetti, her mature way of working was essentially late Pre-Raphaelite yet boldly Celtic in its colour and pattern. Perhaps less known nowadays are her commercial book designs and more ‘ordinary’ easel paintings.

The Awakening, 1904. Oil on panel, 63.2 x 151 cm

The Awakening is one of the latter. Sourced in a sonnet from Rossetti’s The House of Life, Traquair here revisited both her illumination of 1898–1902 (National Library of Scotland) and her ‘awakening of the spirit’ panel (1895–6) in the Catholic Apostolic church. A vivid palette reflects both her recent illumination colours and her new-found medium of painted enamelling. It was later owned by Mrs Charlotte Barbour, a friend for whom a manuscript drawn from her own Song School border details (1897, Edinburgh University Collections) had been commissioned.

Having been turned down for professional membership of the RSA, she was eventually elected HRSA in 1920. Her illustrative art, long out of fashion, was rediscovered publicly in the 1990s with a major retrospective at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in 1993.

Modern Scottish Women: Painters and Sculptors 1885-1965 by Alice Strang is out now published by National Galleries of Scotland priced £18.95.

Modern Scottish Women: Painters and Sculptors 1885-1965 by Alice Strang is out now published by National Galleries of Scotland priced £18.95.

Victoria Williamson, author of the forthcoming children’s book The Fox Girl and the White Gazelle, reflects on her writing process and argues for the need for books to represent diverse experiences of childhood.

One of the first questions a writer gets asked is, “Where do you get your ideas from?”

Sometimes the answer’s easy – “It just popped into my head from nowhere while I was doing the ironing/feeding the dog/burning the dinner.” Other times, a story can take many years to develop, and comes from a complex mix of the author’s real life experience, contemporary issues in the news, and childhood memories. The Fox Girl and the White Gazelle is one of those stories.

My first stories however, were inspired by the books I loved to read. I began as an avid action-adventure fan, devouring The Famous Five, The Three Investigators, The Hardy Boys, and Tintin and Asterix books, before moving on to science fiction and fantasy – The Tripods trilogy, The Dragonlance Chronicles, and The Lord of the Rings. At the time, it didn’t occur to me that there was a connection between the books I was reading and the stories I was writing. It didn’t seem odd that all my main characters were male. On the few occasions I did write a female character, she wanted to be a boy, just like George in The Famous Five. When it came to stories, male characters – mostly middle-class white boys –- were the ones who got to go on action-packed adventures, and that’s just the way I thought it was.

It wasn’t until I became a primary school teacher that I began to question the connection between children’s ideas of themselves, what they thought they could accomplish, and the characters in the books they were reading.

The Harry Potter Project

One year I was teaching a class of six-year-olds in an area of Glasgow with a high number of families seeking asylum. That term we’d been reading Harry Potter, and had spent our art lessons turning the class into Hogwarts, complete with a Diagon Alley word wall, a number train, feather-quill pencils and ‘house points’ for good behaviour. Late one Friday afternoon, the children were enjoying some free play time with the cloaks, broomsticks and cauldrons I’d bought second-hand on eBay. There weren’t quite enough to go round and, before I could intervene, an argument over the last wizard cloak broke out between a girl from the local Glasgow estate, and a boy recently arrived from Sudan.

The Harry Potter Project

“You can’t be Harry Potter!” the little boy yelled, clinging onto the cloak, “you’re a girl!”

“You can’t be Harry Potter either!” the girl shot straight back, holding onto the cloak just as tightly, “you’re black!”

That was definitely an epiphany moment for me.

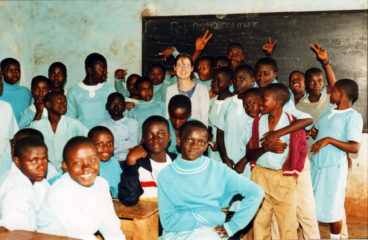

Over the next few years I began experimenting with the characters in my own novels, first with female protagonists, then with characters from many different cultural backgrounds. I’d spent a number of years teaching in Cameroon, Malawi and China, and am ashamed to admit that up until that point, it hadn’t occurred to me include these children in my stories before – such is the power of early experience of representation in our own fantasy lives.

The seeds of The Fox Girl and the White Gazelle were planted that year, the story of twelve-year-old Glasgow girl Caylin and Syrian refugee Reema, both of whom are struggling with difficult childhood experiences and are searching for a sense of belonging. The urban fox that cements their friendship came from the first novel I ever wrote as a teenager, a sprawling trilogy of hundreds of thousands of words and dozens of animal characters, of which only a handful of minor ones (I later realised) were female. Hurriyah, the fox called ‘Freedom’, is my attempt to redress the balance.

Victoria teaching in Cameroon

Childhood memories can also play a huge part in an author’s novels, and many of Caylin’s memories of Glasgow were inspired by my own: weekend trips to stay with my grandparents in Drumchapel, visits to feed the squirrels in nearby Dawsholm Park, and primary school sports days watching in awe as my gazelle-limbed best friend outran all the boys in our class.

The Fox Girl and the White Gazelle is a rich blend of all my life experiences and memories up until now, with as many ingredients as the magic potions my class brewed during the Harry Potter project year that sparked my novel.

Where I’m From Project

Next time you ask a writer, “Where do you get your ideas from?” perhaps take a moment to ask yourself the same question. Do the books you read all feature people who are just like you? Are they all the same gender, with the same cultural background? If so, you’re missing out on countless fascinating stories. If you’re willing to see the world through the eyes of a wide range of diverse characters and learn from their experiences too, that’s when the real adventure begins.

The Fox Girl and the White Gazelle by Victoria Williamson will be published by Floris Books under the Kelpies imprint in April 2018 priced £6.99.

The Fox Girl and the White Gazelle by Victoria Williamson will be published by Floris Books under the Kelpies imprint in April 2018 priced £6.99.

Find out more about the book here, and keep up with news about this stunning debut novel from DiscoverKelpies on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

In this exclusive article Dawn Sinclair, archivist at HarperCollins in Bishopbriggs, delves into the collections to trace how the publishing house evolved from its beginnings in New York and Glasgow in the nineteenth century, to operating across the world today.

As an international business HarperCollins publishers spans the globe. Our beginnings too are international, with J & J Harper beginning their business in New York in 1817. They were successful in making English and American future classics available in America as well as creating the Harper Weekly and Monthly magazines which gave a snapshot of the cultural movements of the time. Two years later in September 1819, William Collins began his business in the city centre of Glasgow on Wilson Street. Each of these parts has its own singular history. As we have reflected on these histories and brought them together as one coherent history for our global bicentenary, it became apparent that due to our founders’ passion, innovation and care for their staff, our archive reflects the stories of our books but equally the stories of our people.

Reverend Thomas Chalmers, c1820s – HarperCollins Archive

Our founder William Collins I began his career in a mill before becoming a teacher. He set up Sunday schools around Glasgow helping people learn the basics of English and Arithmetic. His interest in the temperance movement, as well as his involvement with the Church, led him to securing his first author, Reverend Thomas Chalmers. Our first book, The Christian and Civic Economy of Large Towns, was published on 24th September 1819 and was the first of many books by Chalmers published by Collins.

Collins quickly grew and expanded the business with religious texts, fiction and education books. In 1839 the company gained the licence to print the Bible. By 1842 Collins had published the New Testament in three different typefaces, and the following year the first complete Holy Bible with 4,631,056 letters was set by hand. The first family Bible was then published in 1845 with some editions costing less than £1.

By 1862, Collins became the publisher for the Scottish School Book Association and for the Irish National Education Board. Books for Canadian and Indian schools were also created in Glasgow and exported across the world. The Collins business had a strong presence in Glasgow and the publishing movement within Scotland in the 1800s. Along with Blackie and Sons in Glasgow, and Bartholomew and Chambers in Edinburgh, Scotland was a hub of activity.

Our archive also holds a vast number of photographs, pamphlets and records which show the commitment the Collins family gave to the welfare of their employees and authors. From the earliest days, Collins had pensions for staff, employed hundreds of women and gave many other benefits to the workers. For example, in 1887, William Collins II founded the Collins Institute for his workers. It contained a library, dance hall, dining rooms and games hall for workers to enjoy their recreation time but also for them to gain other knowledge in English and Maths.

Collins Institute, Glasgow, 1920 – HarperCollins Archive

Into the 1900s, welfare was just as important and the company began a Comfort fund for employees who were at the Front. Each person would receive a package of ‘home comforts’ which was paid by the company and staff fundraising. In 1948, the family bought a house in Largs which was a place for employees who were ill to get out of the city, rest, and enjoy the clean air. Holmwood House was open to employees from all levels and ran for nearly 20 years. William Collins I’s strong morals and beliefs continued through the generations of the family members who ran the company, each who appreciated their workers and wanted to provide for them and the local community.

Collins Institute, Glasgow, 1920 – HarperCollins Archive

Our authors are obviously very much part of our history and are present in our archive. From our correspondence collections with famous authors to photographs and ephemera, the archive documents the work of some of the greatest writers. In 1926, we published The Murder of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie and this set us on a long path with Christie which continues to today. Her correspondence with William (Billy) Collins V shows not only a publisher and author relationship but a friendship which grew through time. Alistair MacLean, a Glasgow born author, also holds an important place in our archive. Having discovered Alistair through a writing competition in a local paper, we first published HMS Ulysses in 1955. He went on to write about 30 books for Collins some of which were made into very successful film.

Alistair MacLean at Reception for HMS Ulysses, 1955 – HarperCollins Archive

This is a snapshot of our archive and the wonderful stories it holds. It shows our place in the history of publishing but also within the history of the communities we worked in, the relationships we had with authors and the care the company had for it employees. Having the chance to celebrate 200 years of heritage has been an excellent opportunity to showcase our history and tell the stories which our holds. To learn more, visit http://200.hc.com/.

This article is by Dawn Sinclair, who is archivist at HarperCollins archive in Bishopbriggs, Glasgow.

This article originally appeared in the print edition of New Books Scotland Autumn/Winter 2017.

Coinciding with publication of Heather Richardson’s novel Doubting Thomas, a story of sex, drugs and blasphemy in late seventeenth-century Edinburgh, publisher Vagabond Voices launched a series of podcasts that delve into the potent historical context of the book. Immerse yourself in episode five below.

In this episode Dr Alasdair Raffe, an expert on Scottish religion and politics in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, describes the widespread political and religious conflict in Scotland in these key periods, and explores the ways in which it impacted freethinkers like Thomas Aikenhead. If you haven’t already listened to Episode Two of our podcast, we recommend pairing it with this episode as the two complement each other well.

https://soundcloud.com/freethinkers-footsteps/freethinkers-footsteps-podcast-episode-five-the-politics-of-religion

This podcast is part of Vagabond Voices innovative In The Freethinker’s Footsteps project; find out more about it here.

Doubting Thomas by Heather Richardson is out now published by Vagabond Voices priced £11.95.

Doubting Thomas by Heather Richardson is out now published by Vagabond Voices priced £11.95.

Award-winning children’s author Vivian French teams up with emerging picture book illustrator Hannah Foley in this colourful tale about Billy Hippo who hates water. It’s too cold! Too scary! Too wet! Can two cheeky frogs and a big surprise change Billy’s mind, and start him swimming?

Extract from How Billy Hippo Learned To Swim

By Vivian French; illustrated by Hannah Foley

Published by Little Door Books

How Billy Hippo Learned To Swim by Vivian French, with illustrations by Hannah Foley, is published by Little Door Books in March 2018 priced £6.99.

How Billy Hippo Learned To Swim by Vivian French, with illustrations by Hannah Foley, is published by Little Door Books in March 2018 priced £6.99.

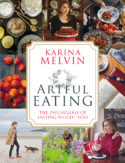

Using powerful psychological tools and strategies to create lasting change, Dr Karina Melvin – a psychologist and psychoanalytic psychotherapist – presents a no-nonsense guide to help you achieve long-term weight loss. Here she introduces her approach which is rooted in the most up to date scientific and psychological research.

Extract from Artful Eating: The Psychology of Lasting Weight Loss

By Karina Melvin

Published by Black and White

Introduction

‘Though no one can go back and make a brand new start,

anyone can start from now and make a brand new ending.’

– Carl Bard

Having spent over ten years training and working as a psychologist and psychoanalytic psychotherapist, I am naturally fascinated by the mind. While everyone is unique, there is a thread of likeness between each person I have the privilege of working with. In fact, it is part of the human condition. Our actions and behaviours constantly contradict what we say we want. This, to my understanding, is evidence of our divided nature. It is never more clearly articulated than in our relationship to our bodies. We say we want to lose weight and get healthy, yet so many people struggle to take action and achieve their goal. What’s even more curious about this contradiction is the fact that the people who struggle are adamant that they want to achieve their desired weight. In fact, they spend a lot of time, money and mental energy trying to do something about it. I know this because I hear it all the time. If you’re reading this, it probably sounds very familiar to you too. There is amazing information available now: television shows, blogs, books, scientifically backed diets, supplements, weight-loss clubs, fitness regimes. The list is endless, yet we are on average actually getting bigger. We are constantly told how to lose weight: eat less, eat healthily and move more. Then why isn’t that working? Despite the abundance of wonderful healthy-eating advocates, obesity is on the rise.

I think it’s time to acknowledge that ‘the diet’ is dead. Research from UCLA examined a wealth of studies on dieting and found that up to two thirds of diets fail, with several studies indicating that dieting is actually a consistent predictor of future weight gain.[1] One study found that people who participated in formal weight-loss programmes gained significantly more weight over a two-year period than those who had not. So the most likely outcome from going on a diet is ultimately putting on more weight than when you started! This leaves a very small proportion of dieters achieving lasting weight loss. If people actually acknowledged this fact, then I am absolutely sure they would never diet again.

Lasting weight loss is not about what you eat. It’s about why and how you eat. As a psychologist and psychotherapist I have come across so many people who are disillusioned and frustrated, feeling guilty about their body and their relationship with food. As a result, people have become obsessed with healthy eating. There are amazing cookbooks and blogs out there communicating the benefits of healthy eating, and while this is a very welcome and positive change, these nutritionists, bloggers and cooks are missing the most vital ingredient in the weight-loss battle: the mind.

By focusing solely on the symptom, the excess weight, we have lost sight of the cause. Take a moment to think about your own relationship with food and your body. When you look in the mirror, what do you see? Do you like the reflection staring back at you? If not, is there any of it that you like? Can you say ‘I like my legs, my smile, my hair’? Or are you consumed with negative thoughts about your body? Are the words that come to mind unkind? Do you respect your body? Do you ever take the time to acknowledge how great it is that you can walk, talk, think, dance, work and share your life with friends and family? Or are you too busy thinking about the weight you want to lose, or all the clothes you can’t wear because of your size, or all the things you just don’t feel comfortable doing until you lose the weight? I want to introduce you to a client who gave me permission to share her weight struggle.

Liz’s story really highlights how our issues with weight go way beyond the simple ‘calories in, calories out’ approach. Liz had tried all kinds of diets, supplements and programmes. A pharmacist in her late twenties, she was well informed about health, how the body works and what she ‘should’ be doing. Liz came to see me at a point when she realised that, after spending years losing and gaining weight, her life was being controlled by food. She oscillated between being ‘good’ and only eating diet readymade meals, and being ‘bad’ and not sticking religiously to this very strict calorie-controlled regime. Being ‘bad’ resulted in bingeing, and the inevitable guilt that followed left her feeling low for days, until she returned to the controlled approach. Liz had completely lost touch with her body. This had a very damaging effect on her relationships, as she didn’t want anyone to truly know the extent of her struggle. On the surface she came across to friends as being carefree and confident, and kept her unhappiness and food issues completely hidden. Prior to engaging in the Artful Eating philosophy, she described herself as anxious, stressed, down and very selfconscious. She told me that she had withdrawn from social situations, refusing to eat out because she couldn’t stick to her diet. Liz was not enjoying food, her body or her life.